Translation was done paragraph-by-paragraph via Google Translate and subsequently correcting or otherwise improving each translated paragraph (precision/accuracy matters in translation of such documents). If you have questions or suggestions/corrections, feel free to contact me.

AIVD Annual Report 2018

Table of Contents

Foreword

In front of you is the public annual report of the AIVD for 2018. The annual report offers an opportunity for us to provide insight into what we, and our two thousand colleagues, have dealt with and deal with globally every day. We hereby account for our work and offer a view of our field of work. It gives politics, press and the public a view of our activities.

In a country under democratic rule of law as we know it in the Netherlands it is, in addition to critical internal checks, essential that there is thorough external control of a service that has far-reaching investigatory powers.

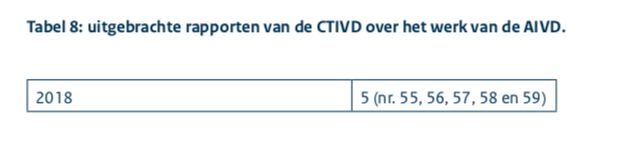

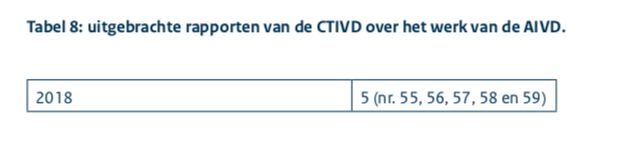

Debates about us in parliament and in the media are often based on the oversight reports of the Dutch Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services (CTIVD). This committee was established per the Intelligence and Security Services Act of 2002 (Wiv2002). Over the past seventeen years, the CTIVD has conducted around fifty quite diverse investigations into the AIVD and has published frank, and largely public, reports on this.

In addition to the CTIVD, the new Intelligence and Security Services Act of 2017 (Wiv2017) that was enacted last year established an additional check on our work. After the minister has approved a request from us to exercise a special power, the independent Review Board for the Use of Powers (TIB) will review the legality of the minister’s decision.

The TIB and the CTIVD are strict and critical in their oversight, and rightfully so. It does not make our work easy at all times, but we as AIVD know that oversight is of great importance to us and to society.

Of course, parliamentary scrutiny also takes place. The standing committee on the Interior supervises the ins and outs of the AIVD to the extent that this is possible in public. With regard to classified and operational information, the minister is accountable to the parliamentary Committee for the Intelligence and Security Services (CIVD) for our actions.

Our work and the law do not allow us to speak openly about our activities. Also in this public annual report we cannot show the back of our tongue. Yet we are not so much a ‘secret service’ – as such you would not know about our existence – but above all ‘a service with secrets’. This is the only way in which we can recognize threats timely. The fact that two committees supervise and report on this gives us our license to operate. They ensure the legitimacy of functioning in a democracy. As a result, society can be confident that we are doing the right thing here and that we are doing it right, in the interest of national security and the democratic constitutional state.

Dick Schoof

Director General

General Intelligence & Security Service

Introduction

The AIVD has not often received so much attention as it did in the year 2018. The reason for this was primarily the new Intelligence and Security Services Act of 2017 (Wiv2017). In March of that year, the Dutch electorate was allowed to vote on that law in an advisory referendum [NOTE: advisory referendum, hence non-binding].

The new law, which entered into force on 1 May 2018, is necessary to cope with contemporary threats at a time when society in all its facets is permeated by and dependent on internet technology.

The Wiv2017 also exists to give citizens the certainty that data are collected as targeted as possible and are only stored if they are important for our work. Other data must be destroyed immediately. From now on, an independent committee will also review the ministerial authorizations to use a special, infringing power before we can actually exercise that power.

We worked hard to prepare our organization to work in accordance with that law before the law entered into force. Yet the implementation of the law turned out to have a greater impact than anticipated. It took more time and effort to implement the safeguards, including independent ex ante oversight, in our work processes because this deeply affects the core of our work: the acquisition and processing of data. This has permanently changed our work.

At the same time, the threats that the Netherlands faces are complex and aggressive. Almost all of them have a significant digital component. Nation-states try to acquire information on decision-making and influence it, to steal trade secrets, and to intimidate and influence their (former) citizens who now live in the Netherlands. They also try to obtain access and persistence in systems for vital processes in our country. This offers them the opportunity to commit sabotage.

The arrest of seven suspects for the preparation of a terrorist attack, as well as some incidents that have occurred, show that our country can still be a target of jihadist or radical Islamic terrorism.

In addition, public debates are polarizing as population groups become increasingly opposed to each other. There is growing suspicion of the government, fueled by, among other things, extremist statements. Certain radical elements also try to separate groups of young Muslims from Dutch society by encouraging them to distance themselves from it.

All this is set against ever-changing international developments.

The situation in the Middle East remains tense and unstable. The security situation in Iraq and Syria is still poor. The so-called “caliphate” of the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) has already lost its ground. The terrorist threat has not diminished. ISIS has gone underground and manages to disrupt the region almost daily with attacks. Al Qaeda is also still active and is manifesting itself more and more.

Chemical weapons were also used in the fight in Syria in 2018. In April, dozens of civilians lost their lives in an attack with chlorine gas on the city of Douma.

The historical contradictions between major players Iran and Saudi Arabia have a decisive influence on the geopolitical situation.

The reputation of the progressive and modernizing Saudi crown prince Bin Salman has suffered a blow after the critical journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed in the Saudi consulate in Turkey.

The uncertainty for Iran is growing now that the United States has withdrawn from the nuclear agreement [NOTE: this refers to the INF Treaty]. The European Union remains committed to the agreement with Iran. The non-proliferation treaty that had its 50-year anniversary in 2018 is under pressure due to increasing tensions, decreasing support for international partnerships and the protectionist attitude of various leaders.

A direct nuclear threat from North Korea seemed to have subsided in 2018 when heads of state Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un shook hands and North Korea said it was prepared to dismantle nuclear facilities. The results of the discussions are very uncertain.

The tension between Russia and the West remains high. President Putin is trying to position Russia as a world power, also to strengthen his position in his own country. He tries to sow discord within NATO and the EU in order to weaken his opponents and acts aggressively towards the Baltic states.

The attempts by the Russian military intelligence service GRU to poison a former intelligence officer in the UK and to hack into the network of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague show the brutality with which this service operates.

On the other side of the world, Venezuela — the largest neighbor of the Kingdom of the Netherlands — is in a deep crisis. The deplorable situation in which the country finds itself, both politically and economically, causes the population to suffer severely. This has led to millions of refugees, which also has consequences for the stability of the areas within the Kingdom, Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. In 2018 we prepared more than 300 intelligence reports on all these developments in the world around us that are important for the Dutch government’s foreign policy. A significant number of the reports served as support for the Dutch membership of the United Nations Security Council in the first half of 2018.

From all our investigations together we have prepared more than 900 written intelligence products, including official messages [in Dutch: “ambtsberichten”], intelligence messages and analyses, risk analyses, threat assessments and information security advice. Increasingly often we also inform our intelligence consumers orally about our findings.

In 2018, the Prime Minister, together with the minister of the Interior and the minister of Defense, set the priorities for the investigations of the AIVD and the MIVD for the coming years. Close consultation was also held with the minister for Justice & Security and the minister of Foreign Affairs.

These agreements are laid down in the Integrated Instruction [in Dutch: “Geïntegreerde Aanwijzing”, or “GA”] on intelligence & security. This states what information authorities need from the AIVD and MIVD to be able to take responsibility for national security. Both services have their own research areas and focus. The GA is evaluated annually.

The national and international developments demonstrate the importance of our work. That is why the government has made funding available for growth of the AIVD in 2018 and 2019. In the past year we have welcomed over 190 new colleagues. In 2019 we hope to attract 200 new employees.

Espionage and foreign interference

We call activities that foreign countries carry out to collect information in and about the Netherlands, and thereby harm our interests, ‘espionage’. Espionage can take place digitally, for example by breaking into a system, or physically by humans. This can be important political information, for example with regard to decision-making processes and viewpoints of the government. Foreign countries can also try to steal (business) secrets through espionage in order to boost their own economy.

Countries can also try to harm Dutch interests in a different way, namely by influencing processes in the Netherlands. We place this under ‘unwanted foreign interference’: covert political influence, influence and intimidation of their emigrated (former) countrymen, sabotage and abuse of the Dutch IT infrastructure. Foreign countries thereby attempt to undermine the Dutch political, economic and social systems.

When states use digital means for espionage and sabotage in order to achieve their own political, military, economic and/or ideological goals at the expense of Dutch interests, we speak of an ‘offensive cyber program’. Our studies show that countries such as China, Iran and Russia have such cyber programs that target the Netherlands.

Espionage

Anyone who has specific or specialist knowledge can be the target of espionage. Not everyone is aware of this. Our research is aimed at protecting the political and economic security of the Netherlands by detecting threats and alerting individuals and authorities in a timely manner.

In the field of espionage, the year 2018 was characterized primarily by the brutality that intelligence officers demonstrated. The attempt by the Russian military intelligence service GRU to gain access to the OPCW network in The Hague shows how far this agency goes.

Our investigations have also shown that digital espionage is becoming increasingly complex. State actors increasingly make use of common methods and techniques, which makes it difficult to determine the origin of an attack (attribution). In addition, state actors are increasingly using internet service providers and managed service providers as a springboard to penetrate a target. These service providers often have in-depth, extensive and structural access to information from organizations or individuals in the course of operating their business. Such methods make detection, analysis and attribution of digital attacks more difficult.

More and more countries are focusing on political and/or economic espionage. We see in our investigations that China, Iran and Russia are at the forefront of this.

Political espionage

To Russia, our country is an interesting target for espionage. The strategic importance of Dutch politics and jurisprudence has increased sharply for Russia since the demise of flight MH17 in July 2014. There is, and will continue to be, a need to obtain information about the course of the investigation into the disaster. The likelihood of this only increases now that the Netherlands has held Russia liable for its share in the downing of the aircraft.

The Netherlands also has Russia’s interest for a long time because of its membership of NATO and the EU. The Russians would like to find out what position the Netherlands takes in these partnerships. In order to gain insight into this, the intelligence services also use classical espionage tools, such as the recruitment of human resources, in addition to digital means.

For other countries, it may be of interest to gain insight into the traffic between a Dutch diplomatic post abroad and the Dutch ministry of Foreign Affairs. We have observed that a number of Dutch embassies in the Middle East and Central Asia were the target of digital attacks carried out by a foreign intelligence service in 2017 and 2018. The digital attacks on these embassies confirm the structural attention of intelligence services for the ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Economic espionage

The biggest threat by far in the field of economic espionage comes from China. This espionage is fueled by Chinese economic policy plans, such as “Made in China 2025” and the “New Silk Roads”, with which the country can increase its economic and geopolitical influence.

These plans not only lead to economic opportunities, but also to increasing competition with Western and hence also Dutch companies. China uses a wide range of (covert) resources to undermine the earning capacity of Dutch companies and which can eventually result in economic and political dependencies. One of these means is (digital) economic espionage.

China is interested in Dutch companies from the high-tech, energy, maritime and life sciences & health sectors.

Another threat to national security is related to globalization. As a result, there is growing economic interaction, digitization, internationalization of labor markets and production processes, and also the liberalization of corporate location and investment policy. This offers more possibilities for (covert) acquisition of Dutch technology and companies. For example, companies can be taken over by foreign companies that are under the influence of their government, or that can easily obtain cheap state funds, creating an uneven economic playing field.

Theft of research findings also takes place within legitimate partnerships between academic and knowledge institutions. This way, Dutch innovations disappear across the border.

The safety awareness and resilience of Dutch business and knowledge institutions against these risks do not seem sufficient. This poses a risk to the economic security of our country.

Covert political influencing

It is perfectly legitimate that a country tries to defend its own interests with and in other countries with an open mind. However, if this transcends regular diplomatic or political lobbying because a country operates under a false flag, we speak of covert political influence.

Covert influence can be directly aimed at political decision-making, but can also take place indirectly if it is aimed at manipulating public perception. The spreading of disinformation is a means that can be used for this. Intelligence services often play a role in covert influencing operations. Russia is a country that has been continuously mentioned in recent years when it comes to interference in the political processes of other countries. It has traditionally been very adept at secretly influencing the image and public opinion in other countries, which can have a disruptive effect on decision-making processes. An example of influencing by Russia is the dissemination of disinformation by proclaiming various speculations regarding the MH17 disaster, which obscures the investigation. We have also found that attempts have been made from Russia, with limited effect, to influence the Dutch online on social media.

We also see that there are states, including China, that try to influence opinions and publications about their own country through educational and knowledge institutions. This may concern countries with which scientific cooperation is relatively fruitful, for example. But that comes at the risk that a dependency on that foreign government arises, for example when investigations are funded by China or when research is conducted that involves a need to travel to that country to carry out research there. That gives that country a certain dominant position that is sometimes abused. Journalists face opposition in a similar way. In the case of unpleasant publications, for example, there may be a threat of withholding work permits.

Countries that we see to be engaged in covert political influencing include China and Russia.

Influencing and intimidating diaspora

States try to influence people in the Netherlands who have emigrated from that country (diaspora), focused on their own domestic political objectives. In some cases, these emigrants still have a passport from their country of origin or have family living there, but have already been living in the Netherlands for some time. It can also be about people who have fled their country of birth for political reasons, and become victims of harassment in the Netherlands. Such intelligence and interference activities create a permanent sense of insecurity in the communities concerned. National tensions from abroad are thereby imported into our country. The influencing sometimes goes so far that people feel limited in the exercise of their fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression. The security services of these states are not afraid to put pressure on the families of emigrants in their country of origin.

Iran is interested in people and organizations that are known to oppose the current Iranian regime. The AIVD has strong indications that Iran is involved in two murders on Dutch territory, in 2015 in Almere and in 2017 in The Hague. Both cases concerned opponents of the current regime. Following the results of the intelligence investigation by the AIVD, the Netherlands has taken measures against two Iranian diplomats.

Countries that we see to be willing to influence and put pressure on their emigrated (former) countrymen include China, Iran, Russia and Turkey.

Sabotage and abuse of infrastructure

States can also pose a threat to the independence and independence of the Netherlands by enabling digital sabotage of vital infrastructure. They do this by gaining access and then embedding themselves in IT systems of vital processes. The AIVD has seen that attempts have been made to this end.

We have not yet detected an intent to actually carry out sabotage actions on Dutch vital infrastructure. A disruption in, for example, the energy supply in countries around us can also have consequences for the Netherlands. The geopolitical unrest in the world makes a sabotage action more conceivable. Russia, for example, has an offensive cyber program for disruption and even sabotage of the vital infrastructure.

The Netherlands also has a special responsibility for the IT infrastructure through which internet traffic flows from virtually all over the world. Just as our country feels responsible for air traffic traveling via Schiphol or cargo ships calling at the port of Rotterdam. Our IT infrastructure is being misused by some countries to carry out digital espionage, influencing and sabotage activities against other countries. These activities harm the international legal order and interests of other countries, in particular allies.

Countries that we see involved in sabotage and/or misuse of the IT infrastructure include Iran, North Korea and Russia.

Activities and results

From our investigations, we have been able to provide insight into the risks of espionage and foreign interference for the Netherlands and for companies. We have visited various agencies, given hundreds of (awareness) presentations and informed government partners such as the National Coordinator for Counterterrorism and Security (NCTV) and various ministries about our findings. The account managers of the intelligence services at the police also play an important role in this.

We have released around 40 intelligence reports on espionage and unwanted foreign interference.

The number of questions to the AIVD about the continuity and integrity of crucial and vital systems within and outside the government has increased in the past year. This is one of the reasons why we have developed and installed accelerated detection tools within the central government to be able to recognize attacks in time. For this, the AIVD had been allocated extra money for 2018.

We were also asked for advice on the risks to national security in the rollout of a renewed C2000 system [NOTE: C2000 is a TETRA-based radio communication system for emergency services; it can also be used by the intelligence services]. The AIVD finds it undesirable that the Netherlands is dependent on the hardware or software of companies from countries for which it has been established that they are conducting an offensive cyber program against Dutch interests for the exchange of sensitive information or for vital processes. We provide insight to involved parties such as ministries about the relationships between such companies and their government, so that they can weigh the risks. It is important to look at the possibilities, intentions and interests of the states involved and the national legislation. It is also important that the Dutch user ensures that he always has control over his own data.

In 2018, the AIVD and the MIVD jointly drew up the Cyber Intelligence Assessment [in Dutch: “Cyber Inlichtingenbeeld”]. This is a classified report written for almost the entire central government and contains an outline of the current threat assessment and expected developments.

With an extra allocated budget, we have strongly focused on recruiting new employees and technical experts for investigations into digital threats. The recruitment of high-quality technical staff and intelligence staff with technical affinity requires considerable effort, certainly in the current labor market.

In the international context, we have worked closely with foreign counterparts and exchanged knowledge with them about developments regarding foreign interference attempts. We were able to provide them with relevant information in specific cases.

Read more at aivd.nl/spionage [only available in Dutch].

(Jihadist) terrorism and radical islam

Within the area of terrorism, the AIVD pays most attention to jihadist terrorism, but terrorism is not solely related to jihadists. The breeding ground for jihadist-terrorist violence can be formed by radical Islam, of which salafism is the best-known variant.

Jihadist terrorism

Last year there was an increase in incidents in the Netherlands with a jihadist, terrorist or radical Islamic background. In the years before, the Netherlands remained unaffected in terms of attacks and there were mainly terrorist incidents in the countries around us. Randomly selected victims fell in stabbings at everyday & freely accessible locations, with apparently little preparation.

Incidents and arrests

Since the murder of Theo van Gogh in 2004, there have been no more incidents in our country by extremist and terrorist jihadists, until last year. A number of incidents took place in 2018 in which the perpetrator probably acted or wanted to act on the basis of a jihadist or radical Islamist motive.

On 5 May 2018 a Syrian man stabbed three people in The Hague. The Public Prosecution Service suspects the man, who has serious psychological problems, of attempted murder with a terrorist motive.

On 31 August 2018 a stabbing took place at Amsterdam Central Station in which a 19-year-old Afghan, who came from Germany, seriously injured two people. The man stated that he wanted to take revenge for a cartoon competition about the prophet Mohammed, which PVV [aka Freedom Party] leader Geert Wilders had announced in the spring.

A few days earlier, a Pakistani was arrested at The Hague’s central train station who wanted to attack the PVV leader for the same reason. The suspect turned to Geert Wilders because, in his eyes, the cartoon competition was insulting the prophet. The Public Prosecution Service charged him with preparing a terrorist attack.

In addition, various arrests were made of jihadists in the Netherlands. For example, the cooperation of the AIVD with various international and national partners on 17 June 2018 led to the arrest of three people in Rotterdam. Two of them are suspected of preparing a terrorist attack in France. It is not ruled out that they also considered Dutch targets.

Perhaps the most striking event in the Netherlands was the arrest of seven jihadists on 27 September 2018. Our investigations showed that they belonged to a jihadist network that originated in the city of Arnhem, and that they were preparing for a large-scale terrorist attack at an event in our country.

The AIVD has been investigating the people involved in a jihadist network in Arnhem for a long time. These members were part of the core of the jihadist movement in the Netherlands. On 25 April 2018 we issued a first official message to the National Prosecutor for Counterterrorism about preparations made by the group to carry out an attack on a large-scale event. In addition, they wanted to make as many victims as possible. It is very worrying that a part of the jihadist movement in the Netherlands has the intention to carry out a major attack on such “soft targets”. The cell is said to have been inspired by ISIS, but most likely operated independently for this attack. The members had contact with other jihadists at home and abroad, but did not share the plans for this attack with people outside their own group.

Jihadist threat against the West

The current jihadist threat is characterized by a constant threat of more complex and relatively simple attacks in and against the West. This is done by globally operating jihadist organizations, such as ISIS and Al Qaida, and smaller jihadist networks or individuals. The incidents of the past year and the many arrests show that the jihadist threat is still present in Western Europe.

Threat from ISIS and Al Qaida

Despite the disintegration of the so-called caliphate and the loss of territory, ISIS continues to pose a threat. In 2018, for example, the organization claimed responsibility in Europe for attacks in Liege (Belgium), Trèbes, Paris and Strasbourg (France). However, the decline of the caliphate and the loss of strength at ISIS have led to a reduction in the attraction to jihadists

Al Qaeda also wants to hit the West with attacks. In recent years it has been able to work on strengthening its organization in the shelter of ISIS. Networks and departments that are counted as Al Qaeda still focus on attack planning against the West.

Threats from foreign fighters

There are two aspects to the potential threat posed by travelers. On the one hand, there are fighters who have left who still choose to stay with terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda and ISIS in Syria and / or Iraq. They are in regular contact with the “home front” in the West. In this way they contribute to the further embedding of jihadist ideas in communities in the West. They use these contacts to encourage people to (support for) attacks.

On the other hand, considerable numbers of fighters from Syria and Iraq have since returned to Europe, including the Netherlands. At the end of 2018, there were around 55.

The returnees include women, with or without children, and men. For each person who returns, the Dutch government makes an assessment of the extent to which this constitutes a threat. At the end of 2018 some 135 jihadists with a Dutch background were among terrorist groups in Syria and Iraq.

The challenge for the AIVD, and for the entire Dutch government, is to find out the purpose for which people return. Have they been disillusioned by the harsh conditions, have they fled and are they missing in Dutch free society? Have they been traumatized by the confrontation with or participation in violence? Are they contacting jihadists in the Netherlands here and are they giving the movement an extra boost? Have they been sent by the organization there to commit an attack in the West or to support it?

Identified returnees are arrested and are on trial. We estimate that some of these jihadists will probably not abandon their ideas during their prison sentence and afterwards. They can join the jihadist networks from which they originate or form new networks.

The Dutch detention system where terrorism suspects and convicts are placed together and not among other prisoners, largely prevents non-extremist prisoners from being radicalized and recruited by jihadists. That does happen in other European countries. The Dutch system can lead to unwanted mutual influence and the formation of new networks. In addition, many detained jihadists will be released in Europe in the coming years. The AIVD expects detained jihadists and released (ex-) jihadists to form an important part of the threat assessment.

The jihadist movement in the Netherlands exists of some 500 persons

The jihadist movement in the Netherlands is a dynamic entity of individuals and groups that adhere to the jihadist ideology.This movement has no hierarchy or well-defined structure. Many jihadists are in contact with each other in both the real and the virtual world. Many undertake activities as a group. Various groups are in contact with each other or with jihadist groups and individuals abroad. In addition, there are jihadists who stand alone and live in isolation from like-minded people.

We count over 500 people as being part of the jihadist movement in the Netherlands.Several thousand people in the Netherlands sympathize with jihadist ideas without really belonging to the movement.

The jihadist movement in the Netherlands is mainly pro-ISIS, but there are also jihadists who align more with Al Qaeda. In recent years the movement has been very focused on the war in Syria and the caliphate of ISIS. More than 300 jihadis traveled to that region. Now that there is no longer a physical caliphate, that focus has decreased. There is a phase of reorientation in which the jihadists are now focusing more on spreading their teachings or ideology and on strengthening their networks.

Whether the movement becomes larger and more powerful depends on several factors. This includes the emergence of new leaders and new sources of inspiration, or issues that arise and can re-mobilize the movement. The war in Syria was such a momentum at the start of this decade. Even in the current phase of reorientation, the jihadist movement in the Netherlands is threatened, as demonstrated by, among other things, the arrests of the Arnhem network.

Unconventional means of attack

Last year, incidents took place that involved the possible use of unconventional means of attack in the form of biological substances, such as in Germany and Italy. We see that such knowledge is disseminated by including the manuals for making and using chemical agents and biological poisons in propaganda expressions.

Activities and results

In 2018 we published more than 100 intelligence reports on developments within jihadist and radical Islamic terrorism. We were able to provide the Public Prosecution Service with information about their criminal investigations via 35 official messages. In addition, we have issued official reports on this to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (8 reports), to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (3 reports) and to mayors (2 reports). We also issued a publication on the state of affairs with regard to ISIS and Al Qaeda in relation to the struggle in Syria. [FOOTNOTE 1: ‘De erfenis van Syrië, mondiaal jihadisme blijft dreiging voor Europa’, AIVD, November 2018.]

Cross-border threats require a cross-border response. International cooperation between colleges remains crucial in the fight against terrorism, as was proven again in 2018.

This collaboration is partly anchored in the Counter Terrorism Group (CTG). This is a collaboration between the security services from the EU countries plus Norway and Switzerland. The platform, based in our country, that directly shares information about jihad fighters, simplifies cooperation and contributes to gaining a better understanding of transnational and international connections.

This cooperation strengthens our intelligence position and that of the affiliated partners. Specifically, this cooperation leads to the earlier recognition, identification and arrest of potential jihadist perpetrators in Europe.

Read more at aivd.nl/terrorisme [only available in Dutch].

Radical islam

The AIVD’s investigation into radical Islam focuses on two types of threat that can arise from radical Islam. On the one hand there is the threat of further radicalization towards the (violent) jihadist ideology. On the other hand, there is a threat to the democratic legal order from an intolerant religious ideology. We are dealing here with a phenomenon that is at odds with our democratic legal order, but is still moving within the legal frameworks. Our research focuses largely on certain driving factors in the Salafi spectrum.

Unwanted foreign investments

The AIVD investigates the extent to which Islamic institutions receive financial support from abroad, including the Gulf States. This support can be accompanied by interference on an ideological level. If this foreign influence poses a threat to the democratic legal order, it has our attention. We work closely together on this issue in a European context.

Radical influence within education

The AIVD notes that radical Islamist promotors are able to position themselves strongly within the range of education for young Muslims. For example, after-school lessons in Arabic and Islam. Such educational programs are also attractive for pupils with a moderate background.

This is partly due to the fact that they often have few or no good alternatives to after-school Islamic education.

At first glance, these educational initiatives appear to be easily accessible and innocent. However, we believe that children and young adults are alienated from society by this interpretation of education and may be hindered in their participation in society. This is caused by the intolerant and anti-democratic ideas of the initiators. In the long term, this can put social cohesion under pressure and thereby undermine the democratic legal order.

In the past, only a few established mosques and educational institutions spreaded this philosophy, but the offer has now become widespread. A new generation of eloquent preachers has been trained and is developing their own initiatives to spread their message. Online drivers also see opportunities to reach their target group quickly and easily. Our research also shows the influence of a few individuals who adopt a dual attitude towards (violent) jihadist ideology, because they are not directly opposed to it. This may create a breeding ground for jihadism.

Activities and results

Six official messages and 12 intelligence reports were issued on developments regarding radical Islam.

The AIVD collaborates on this with the NCTV, various ministries and local authorities. We support both national and regional governments based on concrete examples.

In this way we offer tools with regard to a phenomenon that is at odds with the democratic legal order, but that is (still) mainly lawful. In the past year we have given presentations to various municipalities and other government partners.

Read more at aivd.nl/radicalisering [only available in Dutch].

Non-jihadist terrorist organizations

The AIVD notes that in 2018 the Kurdish Workers Party PKK did not intend to carry out attacks in Europe. The PKK’s primary goal is to be removed from the EU list of terrorist organizations. The use of force in Europe would not contribute to that. However, the organization does have the potential for violence and is able to mobilize PKK supporters in a short time.

The PKK organized solidarity demonstrations in Europe – also in the Netherlands – for the victims who fell as a result of the Turkish military action in the Syrian Afrin. Under the name #fightforAfrin, arson attacks against Turkish targets were committed in a number of European countries – particularly in Germany – resulting in property damage. The call for this came from a youth group that is not officially covered by the PKK, but possibly linked to it.

Activities and results

In the context of the investigation into non-jihadist terrorist organizations, we issued 4 intelligence reports and 2 official messages in 2018.

Read more at aivd.nl/terrorisme>[only available in Dutch].

Extremism

Extremism is the active pursuit and/or support of profound changes in society that can endanger (the continued) existence of the democratic legal order. This can happen with undemocratic methods, such as violence and intimidation, which can undermine the functioning of the democratic legal order.

Although the themes within extremism in general still have a “left” and “right” signature, that subdivision can no longer always be made. Indeed, there are beliefs about which both “left” and “right” are concerned. This is often the result of discontent and mistrust of the government.

In most cases, civil disobedience is involved, such as during protests against nature policy in the Oostvaardersplassen and against gas extraction in Groningen. These protests usually do not transcend activism and therefore there is no immediate threat to the democratic legal order.

We do, however, consider it conceivable that splinter groups or loners will be inspired by activism and seek refuge in extremism. The AIVD has the task of identifying when this activist anger degenerates into extremist activities.

Hate of the foreign/unknown, preference for own race

For certain right-wing extremists, immigration is still synonymous with Islamization. In their view, immigration and Islamization pose a danger to Dutch identity.

For these right-wing extremists, it feels like the government is selling Dutch culture by admitting refugees from Islamic countries. A visible representative of that philosophy is, for example, the group Identitair Verzet [in English: Identity-based Resistance].

The anti-Islam position has many supporters inside extremism, with men becoming less and less exclusive as before. The anti-government sentiment that prevails within this group also attracts sympathizers who have no history of right-wing extremism. They also have distrust of (European) politics and sometimes also of science and (mass) media.

It goes without saying that the AIVD does not consider criticism of Islam, immigration or the government itself as a form of right-wing extremism. After all, such opinions are protected by the freedom of expression. We view such expressions as extremist when they turn into hate speech, intimidation and threats.

Some of the extremists even argue for the prevention of mixing of races. This ethnic-nationalistic ideology is heard within the circle of supporters of the alt-right ideology, such as the “study society” Erkenbrand. In themselves, they say they have nothing against the existence of multiple races, but the Netherlands is for the Dutch.

There are also extremists who are convinced of white supremacy. These people take an anti-democratic position and pursue a racist society in which people are not considered equal. This is contrary to the democratic legal order.

Resistence against ’cause’ of migrant flows

From the “left” there has traditionally been opposition to immigration and asylum policy. The policy is considered to be too strict.

Within the opposition to the immigration and asylum policy, a shift of attention can be seen towards defense industry companies. These are companies that deliver goods to the Ministry of Defense. The reasoning is as follows: without defense order companies there would be less war, so fewer refugees and therefore fewer migrant flows. Companies are also charged for supplying materials to the European Border Guard to stop migrants at the European external borders. The Anti-Fascist Action (AFA) last year joined a number of non-violent campaigns against these types of companies.

In addition, attention is also paid to the “traditional” targets, such as the makers and implementers of the immigration and asylum policy, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the National Agency of Correctional Institutions and the construction companies of detention centers. Actions against asylum policy were conducted less strongly last year than a few years ago.

Ideology based on own identity

A notable development within activism and extremism is the fragmentation of ideologies that fall back on one’s own identity.For example, there are organized anti-racists based on their own identity who oppose the — in their eyes — colonial legacy of the Netherlands and who reject the support of “white” supporters.

Activities and results

Based on official messages from the AIVD, the Public Prosecution Service has launched a criminal investigation into an extremist who wanted to use violence against Muslims. This ultimately led to a conviction by the court in early December 2018.

In 2018 we issued a total of 21 official messages related to extremism and prepared 8 intelligence reports. On the developments within right-wing extremism we published “Right-wing extremism in the Netherlands, a phenomenon in motion” in October 2018. [FOOTNOTE 2: “Rechts-extremisme in Nederland, een fenomeen in beweging“, AIVD, October 2018.]

Read more at aivd.nl/extremisme [only available in Dutch].

For a secure Netherlands

The chapters above deal with the threats that we see for national security and the risks that exist for Dutch interests. We inform various partners with unique information relevant to them from our investigations. With this we enable them to take their responsibility for national security. We call this the creation of an action perspective.

The AIVD itself has limited possibility to take action. But with an official message, for example, we offer the Public Prosecution Service handles to start a criminal investigation into activities that pose a threat to national security and that can also be prosecuted.

In addition, this concerns information for, for example, ministries, executive organizations, mayors, educational institutions and also companies. The latter are especially important when they play a role in vital processes in our society. Think of companies from the energy sector or civil aviation. We want to promote the resilience of the Netherlands by informing, informing and, where possible, advising all these authorities about threats that could affect them and therefore anyone in the Netherlands.

There is also frequent cooperation with Dutch parties that play a role in export control, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and customs. We are regularly asked for advice regarding an application for an export license. In addition, we have informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs several times about unsolicited acquisition attempts that have been identified. This often concerns goods that can be used for the development or production of weapons of mass destruction or their means of delivery.

We also provide information to relevant parties about the risks of involvement in the dissemination of knowledge and goods for weapons of mass destruction (proliferation). We advise them on what they can do to identify suspicious transactions. In this way we have been able to recognize and prevent various acquisition attempts.

In 2018 we issued 32 official messages to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with regard to proliferation and export control.

Read more at aivd.nl/massavernietigingswapens [only available in Dutch].

“Safe” people in trusted/essential functions

At various places in society, positions of trust exist where an employee can harm national security. These positions exist among others at the central government, the National Police and companies involved in critical infrastructure.

Preventing the acquisition of knowledge and goods

Countries such as Iran, Pakistan and Syria are looking towards the Netherlands and other Western countries for the knowledge and goods they need for the development of weapons of mass destruction. In a joint unit of AIVD and MIVD we are investigating how these countries are trying to obtain the required knowledge and goods and we are trying to prevent this. To this end, intensive knowledge was exchanged with fellow foreign services in the past year.

The positions of trust are designated by the relevant minister. We conduct security investigations to assess whether we can issue a “declaration of no objection” (VGB) to a (candidate) trust officer. We also enable the relevant authorities to take responsibility for national security by conducting security investigations.

The Ministerial Regulation on Security Investigations Unit entered into force on 1 October 2018. [FOOTNOTE 3: Ministeriële regeling over taken van de Unit Veiligheidsonderzoeken, Staatscourant, nr. 53581, September 2018.] This creates the framework for merging the AIVD’s Security Investigations business unit and the MIVD’s Security Investigations Office Safety investigations (UVO). In anticipation of this cooperation, the policy of the MIVD and AIVD in the field of security investigations was aligned per March 2018. [FOOTNOTE 4:

Beleidsregel Veiligheidsonderzoeken, Staatscourant, nr. 10266, 21 Februari 2018.] First steps were taken in 2018 to also standardize the work processes of both organizations. The idea behind merging is: one policy, one system, one location.

Also in 2018, the electronic Personal Information Form (eOPG) became available for some of the employers. This is currently only available for investigations carried out by the AIVD. The process has been fully digitized for this group. This concerns the application that the employer makes and the personal information that the employee must enter for the investigation. The people who have to undergo a safety investigation log in with DigiD in a secure environment.

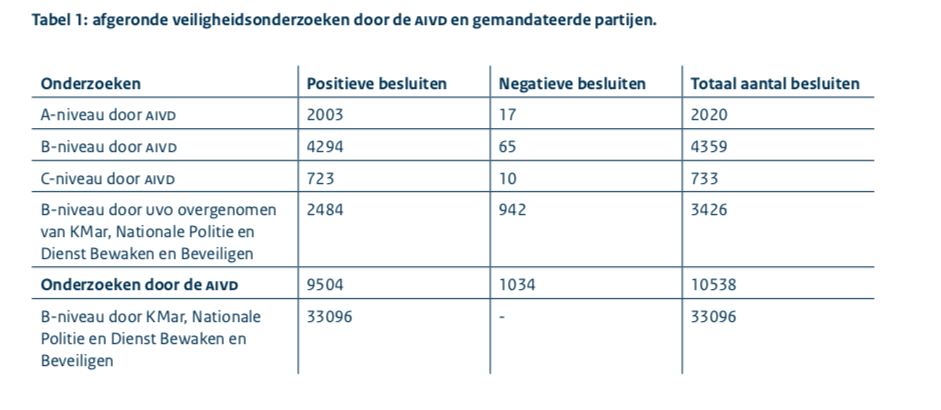

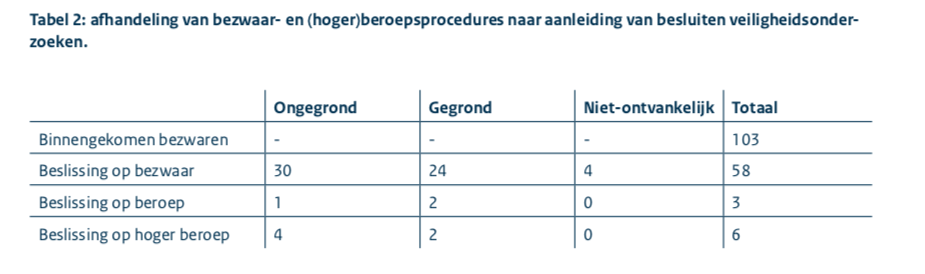

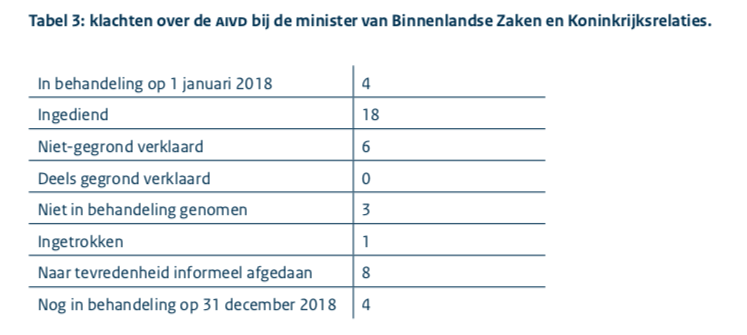

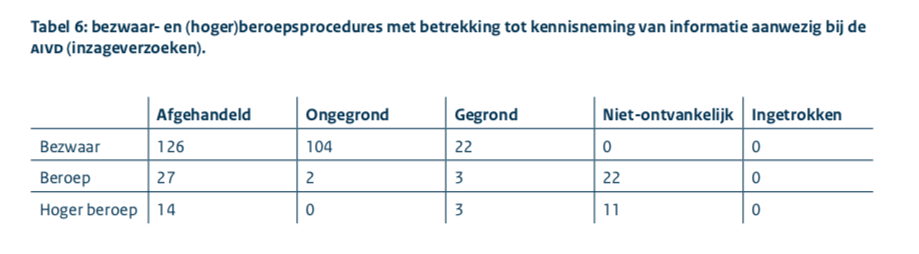

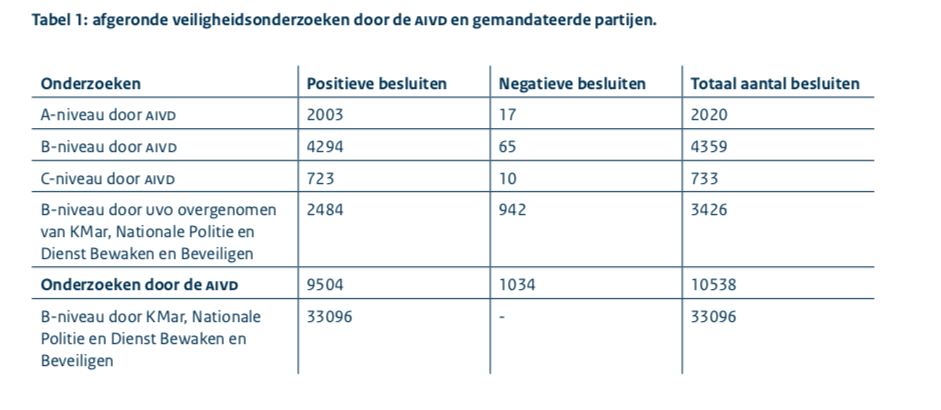

In 2018, the AIVD and the mandate holders (National Police and Royal Netherlands Marechaussee) jointly carried out nearly 44,000 security investigations into persons who (wanted to) assume a position of trust. That number hardly deviates from the number of investigations (more than 45,000) conducted in 2017.

The point of departure is that 90% of the security investigations conducted by the AIVD itself must be completed within the maximum legal decision period of 8 weeks. With nearly 89%, this goal was almost achieved.

The main cause of this is the substantially increased inflow of the number of security investigations. The AIVD completed almost 20% more investigations in 2018 than in 2017. This increase is almost entirely due to the increased demand for investigations in civil aviation, which we had to handle. In addition, preparation for the joint Security Investigations Unit also used available resources.

Screening of a person at the request of others

In addition to the security investigations, another type of screening is part of our duties. In those cases we look up information about specific persons in our own systems. This is done at the request of others. An example of this is a request from the Prime Minister for a reference screening of a candidate-minister of government.

This type of screening via our own systems was not explicitly laid down as a task in previous law, i.e., the Wiv2002. With the introduction of the Wiv2017 law this has become an explicit task.

In 2018 we conducted 31 reference screenings and issued official messages about the results to the relevant authorities.

Read more at aivd.nl/naslag [only available in Dutch].

Role in the protection of persons

Just like the MIVD, the National Police and the NCTV, the AIVD has a role in the Monitoring and Protection System for the protection of certain persons. This system is aimed at the safe and undisturbed functioning of dignitaries such as politicians and members of the Royal Family, diplomatic representations and international organizations.

The essence of the system is that it not only looks at the concrete threat of, for example, jihadist terrorists and left and right extremists, but also at conceivable threat. With risk analyses, threat analyses and threat assessments we enable the NCTV to decide on possible security measures.

In the past year, we have drawn up a total of 1 risk analysis, 10 threat analyses and 51 threat assessments in the context of the Monitoring and Protection System.

Read more at aivd.nl/bewakenenbeveiligen [only available in Dutch].

Information security

One expertise of the AIVD is advising the central government on the protection of confidential and state-secret information. We also develop means ourselves to keep such information secure.

One of the contributions to better information security is the preparation of the National Cryptovision and Strategy, which was initiated in 2018. This is done together with other departments. The business community and knowledge institutions also provide input for this. The National Cryptovision and Strategy describes how cryptographic security measures to protect sensitive information will continue to be available in the future.

A lot of oral presentations were given to stakeholders from the National Communication Security Agency [NBV, aka NL-NCSA] of the AIVD last year. In addition, 44 written threat intelligence products were released.

Read more at aivd.nl/informatiebeveiliging [only available in Dutch].

A new law

On 1 May 2018 the new Intelligence and Security Services Act, Wiv 2017, entered into force. The law is a consequence of the report of the Dessens commission from 2013 that concluded that a change to the old Wiv (from 2002) was necessary because it was no longer adequate. [FOOTNOTE 5: ‘Evaluatie Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 2002’, 3 December 2013.] In order to continue to carry out our duties, modernization of our investigatory powers was necessary. In addition, the law offers a considerable reinforcement of privacy guarantees.

Modern investigatory powers

The speed of technological developments was not taken into account in the Wiv 2002. Nowadays, everyone uses Internet applications for communication and other data exchange. This leads to data traffic that rages across the world in large quantities and with great speed via cables. Regarding communication transported “on the cable”, the old law only allowed interception based on a specific selector/characteristic of a specific person or organization.

The essence of the AIVD’s work is to make unprecedented threats visible. Without access to digital data streams, it is not possible to identify new threats. An example: if we know that digital attacks on the Netherlands are being carried out frequently from a certain part of the world and we have been able to find out via which fiber optic traffic that traffic is running, then we can investigate that data flow for characteristics that we extract from the attacks. In this way we can determine in time what the attack is aimed at, not after the malicious software has already reached the target and caused damage.

The technology for this research assignment-oriented (OOG) interception on internet cables requires extensive technical preparation. In 2018 we have therefore not yet exercised this power.

Safeguards

The use of internet technology results in large amounts of communication data, and all types of such data are mixed. This means we can potentially make bigger infringements on privacy and regarding more people.

For example, when intercepting and investigating certain data flows through research assignment-oriented (OOG) interception, there is a risk that we will also intercept traffic from people who do not mean any harm. Intercepted data that is determined to be irrelevant to our investigation is immediately destroyed. This concerns approximately 98% of the data collected.

Under the Wiv2002, the use of a large number of special powers required permission from the minister of the Interior. With the Wiv2017, after the minister’s approval and prior to exercise of powers, approval is also required from the independent Review Board for the Use of Powers. Moreover, the Wiv2017 prescribes stricter retention periods than its predecessor.

In the advisory referendum of 21 March 2018 on the Wiv2017, 49.4% of the voters voted against and 46.5% voted in favor of the law.

After the referendum, the government promised extra guarantees to address the outcome of the referendum. For example, it was promised that the consideration notes on foreign cooperation partners would be completed earlier than prescribed by the law (1 May 2020), namely before 1 January 2019. For all foreign services that we have a cooperation with, the written considerations have been completed. A consideration note assesses the extent to which a foreign counterpart and the country in question meets legal criteria and to what extent cooperation is possible.

Furthermore, wee will also ask the minister for approval on an annual basis for (further) retaining the data we collected via research assignment-oriented interception. There was no such interim assessment prescribed in the original law. We have to substantiate whether, and if so, why we still want to save them in order to determine relevance at a later date. After 3 years, the data will be destroyed regardless, except of course for the data that we have determined to be relevant to our investigation.

A policy rule is drawn up that, when requesting approval for the use of a special power, we must state explicitly how we want to use a power “as targeted/focused as possible”, in addition to the standing requirements of necessity, proportionality and subsidiarity.

The government virtually excludes that OOG interception will be used in the coming years for research into cable communication that has its origin and destination in the Netherlands [NOTE: this refers to domestic-domestic communication. Communication between Dutch citizens that takes place via foreign providers, such as Facebook and the like, travels via the US and is considered domestic-foreign communications under the Wiv2017]. An exception to this is research into digital attacks in which the Dutch digital infrastructure is abused. OOG interception may be needed to detect such threats.

Processing of medical data is permitted only if it occurs in addition to the processing of other data, that is, if someone is the subject of an ongoing investigation and the medical data forms the final piece of information that AIVD needs to properly identify a threat. If the AIVD encounters medical data that we are not allowed to view, we will immediately remove it.

Careful consideration is always given when sharing data about a journalist with foreign services. This also takes into account the [societal] function of an individual and the protection of their privacy and security. If the services determine that a journalist is present in data collections, they will not share that data unless it is necessary for national security. [FOOTNOTE 6: Kamerbrief met reactie op raadgevend referendum Wiv, dossier 34588, nr. 70]

Impact on our work

The core of our work consists of acquiring and processing data. The new law and the additional safeguards for citizens in the form of, among other things, independent ex ante oversight and stricter retention periods have led to extra efforts for us.

As is apparent from this annual report, the geopolitical developments and the threat assessment also demanded great commitment from our employees. It has proved difficult to combine implementation of the new law with a non-decreasing commitment to operational task performance. The impact of the implementation was greater than initially anticipated.

For example, the ex ante approval process by the TIB required habituation. In an interim report from the TIB in November 2018, the TIB indicated that they rejected approximately 5% of the requests for approval. [FOOTNOTE 7: Voortgangsbrief Toetsingscommissie Inzet Bevoegdheden, TIB, 1 November 2018.]

In addition, at the request of the government, the Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services (CTIVD) carried out a baseline measurement and published a report on it. This critical progress report, released in early December, gave a first insight into progress of the implementation of the new law. [FOOTNOTE 8: Voortgangsrapportage Commissie van Toezicht op de Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdiensten over de werking van de Wiv 2017; CTIVD, 4 December 2018.]

The CTIVD’s investigation focused on elements of modernized powers such as the duty of care, responsible limitation of data processing, and OOG interception (including automated data analysis).

The committee also looked at the other parts of the law that provide for the protection of citizens. The CTIVD investigated the available possibilities for submitting a complaint or reporting abuse.

The CTIVD indicated in its progress report where the service ran the risk of unlawful acts. She based her judgment on the policy and procedures as they were designed and set up at that time. The CTIVD did not find actual cases of an illegal act.

The committee also described in its report that many parts of the law are very complex, such as the principle of data reduction. This involves the destruction of data that appears to be irrelevant. This requires the necessary adjustments in the system and in technical implementation.

The reports from the TIB and the CTIVD gave us the signal to establish implementation of all facets of the law as a priority for 2019, in addition to our primary duties. We seek a considerable reduction of the risks identified by the TIB and CTIVD in their next reports.

Read more at aivd.nl/nieuwewiv [only available in Dutch].

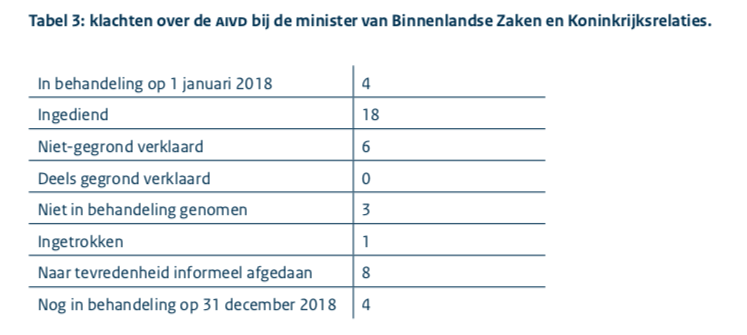

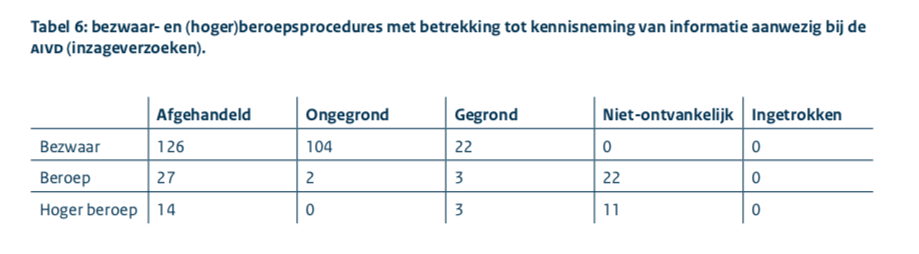

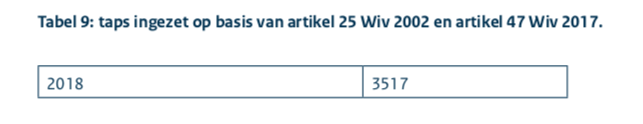

Appendix: statistics [in original Dutch; not translated]