UPDATE 2015-04-10: today, a week earlier than announced, the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR) published (.pdf, in English; mirror) WRR-Policy Brief 2, entitled “The public core of the internet: an international agenda for internet governance”.

The Dutch Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR) sent a report (.pdf, in Dutch) regarding internet-related foreign policy to the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bert Koenders. The report is a call to action for the Minister to implement three recommendations:

- “Promote the establishment and spreading of the norm that the public core of the internet — the central protocols and infrastructure that are a global public good — must be free of government interference.”

- This considers the establishment of neutral zones that governments are not allowed to interfere in for the purpose of pursuing national interests, and argues that non-interference is in the interest of all countries.

- “Promote that different forms of security in relation to the internet are distinguished from each other nationally and internationally and are addressed by separate actors.”

- This considers the undesired blend of “security” in terms of CERTs that have a public health-like function for networks vs. “security” in terms of national security, the domain of intelligence services and military cyber units.

- “Make expansion of the diplomatic field a part of the agenda for internet diplomacy.”

- This considers the upcoming participation from countries in the East and South that have economical and political views different from those held by the current powers that be.

These recommendations are unrelated to, but not inconsistent with, the recommendations made in December 2014 by the Dutch Advisory Council on International Affairs (AIV) concerning internet freedom.

Alas, no English version is available of the new WRR report (yet?). According to the WRR website, a Policy Brief on this report will be published on April 16th 2015, during the Global Conference on Cyber Space (GCCS) 2015. The website further states:

International protection of the internet is a matter of urgency

The growth and health of our digital economies and societies are dependent on the backbone protocols and infrastructure of the internet. This backbone is now in need of protection against unwarranted interference to sustain the growth and the integrity of the internet. The internet’s backbone of key protocols and infrastructure can be considered a global public good that provides benefits to everyone in the world. Growing state interference with this backbone underlines the need to set a new agenda for internet governance that departs from the notion of a global public good.

Here is a translation of the report’s summary (~2100 words):

Summary

This report intends to contribute to creating the Dutch agenda for a foreign policy regarding internet. The core thought is that the central protocols and infrastructures of the internet must be considered a public good globally. This public core of the internet must remain free of inappropriate interventions by states and other parties who harm and undermine public trust in the internet.

States strengthen their control over the internet

Internet has become indispensable in our daily lives. It is interwoven with our social lives, consumption, work, relation to the government, and increasingly with objects that we use on a daily basis, from the smart meter to the car we drive and the drawbridge we travel across. For a long time, the administration of the internet was the exclusive domain of what is called the “technical community” in internet circles. That community laid down the foundation for the current social-economic interweaving of the physical and digital life. But the management of the foundation, with the Internet Protocol as its most prominent part, has become controversial. Because of the many interests, opportunities and vulnerabilities of the internet, many governments have gotten involved in it. The policy focus has shifted from a primarily economical view on the internet (the internet economy, telecommunications and networks) to a view determined by (national) security: the internet of cybercrime, vulnerable critical infrastructures, digital espionage and cyber attacks. Moreover, an increasing number of countries want to regulate citizens’ behavior on the internet for varying reasons: from protection copyright and addressing cybercrime to censorship and control over their own population.

The fact that national states demand their space and role on the internet, can have consequences for the crucial foundation of the internet. The internet has been made to function internationally, without regard of persons or nationalities, a basic principle that serves all users. It is mostly the deeper technological layers of the internet, consisting of protocols and standards, that enables information to find its way, and arrives in all parts of the world. When these protocols and standards do not function properly, the functioning and integrity of the entire internet is under pressure. The internet can “break” if we cannot rely on information we send to arrive at its destination, that we find the sites we are looking for, and that they are accessible. Recently, more states have started specifically using the deeper layers of the internet to serve national interests.

Considering the huge stake that is the internet, national and international interests of states must be given more weight within the governance structure. At the same time, it is necessary to be careful that the technological core — on which the growth of the internet is built — is not damaged, and to protect it against inappropriate use. The question how national interests and the governance of the internet as global public good can be balanced, must of course be answered internationally. That requires a clear standpoint from the Netherlands.

The public core of the internet

To that end, this report first argues that parts of the internet have the characteristics of a global public good. In global public goods it is about benefits for everyone in the world that can only be realized and maintained by direct action and cooperation. These benefits mostly follow from the core protocols of the internet, such as the “TCP/IP protocol suite”, various standards, the domain name system (DNS) and routing protocols. The internet as public good only functions if it ensures the core values of universality, interoperability and accessibility, and if it supports the core objectives of information security, namely confidentiality, integrity and availability. It is crucial that we — the users — can rely on the functioning of the most fundamental protocol of the internet, because the trust we have in the social-economic structure built on top of it, depends on it. Although it is inevitable that national states want to shape “the internet” to their own image, ways should be found to ensure the general functioning of this “public core” of the internet.

Two forms of internet governance

To provide insight into this tension, two forms of internet governance are distinguished in this report. In the first place, governance of the internet infrastructure. This involves the governance, organization and development of the deeper layers of the internet, that give direction to the development of the internet. The interest of the internet as collective infrastructure is paramount in this. Opposing this, is the governance that uses internet infrastructure. In this case, the internet is used as a means to control contents and behavior on the internet. That can vary from protecting copyrights and intellectual property to the censoring and surveillance of citizens by governments. Increasingly often, the infrastructure and the central protocols themselves are considered to be legitimate instruments to pursue national or economical interests. Whereas internet governance used to be primarily governance of the internet — in which administration and functioning of the internet is put first —, there now increasingly is governance via or using the internet.

Threat within the governance of the internet

The administration of the public core of the internet — the governance of the internet — resides at a number of organizations that are often together referred to as “technical community”. Although it is in principle in good hands, pressure is building from various angles. Political and economical interests, and differences of opinion — sometimes combined with new technological possibilities — challenge the collective character of the internet:

- Large economic interests — such as the protection of copyright and business models for data transport — put large pressure on politics to eliminate net neutrality, formerly a default of the internet, are in fact protect it through legislation.

- The administration of names and numbers of the internet (the IANA function) has become politicized. For reasons of international political legitimacy, there is large pressure to remove that administration from the immediate sphere of influence of the US: after all, it is of vital importance to nearly all countries. The Netherlands is served by an “agnostic” shaping of the IANA function, in which administrative tasks remain in the hands of the technical community, and that more political tasks allow room to accommodate the political and economical interests.

- The discussion about ICANN (which carries out the IANA function) is also an important test case for the Dutch and European internet diplomacy to bring the formation of international coalitions beyond “the usual suspects” of the transatlantic axis.

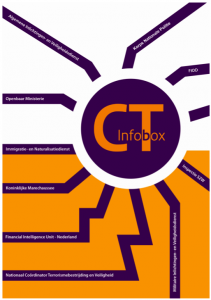

- Another challenge is the rise of national security thinking on the internet. The engineers approach of the CERTs (aimed at keeping the network “healthy”) and the international cooperation therein are hindered by actors focused on national security, such as intelligence services and military cyber units. A mixture of these views is undesirable, because the partial interest of national security opposes the collective interest of the security of the network as a whole.

Threats resulting from governance via the internet

States also directly target the public core of the internet, for various interests. They sometimes affect central protocols. Such practices undermine the reliability and security of the functioning the entire internet. Firstly in technical sense, but in extension of that also in economical and socio-cultural sense: if we cannot rely on the integrity, availability and confidentiality of the internet, that has consequences to the manner in which we want and can use it. The tension between political and economical interests on the one hand, and the interests of the internet as a public infrastructure on the other hands, become clear in dossiers such as:

- Legislation that should protect copyrights and uses protocols and the DNS as a means, such as the American legislative proposals SOPA and PIPA and the ACTA design treaty.

- Various forms of censorship and surveillance that use vital protocols and the “services” of internet intermediates such as ISPs.

- The online activities of intelligence & security services and military cyber units that undermine the integrity of the public core of the internet by compromising hardware, software, protocols and standards, and keeping vulnerabilities in hardware and software secret.

- Some forms of internet and/or data nationalism in which states seek to shield off a part of their internet.

On the basis of these findings, this report concludes that governments must act with serious restrain regarding policy, legislation and operational activities that affect the core protocols of the internet. This also applies to private parties that fulfill a key role considering this public core.

Towards a foreign internet policy

What contribution can the Netherlands deliver? The overarching interest of internet security firstly assumes a diplomatic approach in which the internet — explicitly and independently — is raised to a spearhead. Next to traditional spearheads such as trade, human rights and peace & security, the government should prioritize and develop a foreign internet policy. For a small, but relatively influential diplomatic actor in this field such as the Netherlands, “practice what you preach” must be the most solid basis to act as a role model. In new national legislation, the question whether the Netherlands can justify it internationally, must be an important consideration. On the area of fundamental rights and internet policy, the Netherlands should consistently get a passing grade to really claim a leader’s role.

This role entails a diplomatic effort aimed at protecting the public core of the internet. The protection of the public core of the infrastructure thus requires, in addition to political action in states, also a large restraint from those same states. To achieve that, new forms of power and dissent must be organized. The principles of mixture, separation and restraint, three classic principles of bonding power, must therefore be translated to the international context.

Recommendations

The central recommendation that the internet must explicitly be a spearhead of the foreign policy is further developed in this report into three recommendations:

- Promote the establishment and spreading of the norm that the public core of the internet — the central protocols and infrastructure that are a global public good — must be free of government interference.

Firstly, it is about an international norm in which the central protocols of the internet are marked as a neutral zone, in which government interference on behalf of national interests is not allowed. In five year, a much larger group of countries have the technical capabilities that are now only in the hands of a few superpowers. If meanwhile also the norm arises that national states can freely determine whether they want or don’t want to intervene in the central protocols of the internet for reasons of national interest, that has a very damaging effect on the internet as a global public good.

A number of important fora are available to the Netherlands for establishing and spreading this norm. Firstly, the EU, and via the EY also trade agreements in which such a norm could be included as a clause. Fora such as the Council of Europe, the OECD, the OSCE and the UN also provide possibilities to anchor this norm. A seed can be planted that can grow to a wider regime over time.

- Promote that different forms of security in relation to the internet are distinguished from each other nationally and internationally and are addressed by separate actors.

Secondly, it is about making distinction between various forms of security related to the internet. That requires a strict demarcation and a separation of duties and organizations, and mostly also a restraint of the tendency of states to make national security the dominant view of the internet. Notably the technical approach by CERTs, who have a more “public health”-like approach of the security of the network as a whole, and the approach from national security, in which national interests are put before the interest of the network, must remain separated.

- Make expansion of the diplomatic fielda part of the agenda for internet diplomacy.

A demographic shift is taking place on the internet: away from North and West, towards the East and South. Other voices than the European and American one will in the near future speak louder, and will contain different economical and political ideas. It therefore is important to pursue a wide diplomatic effort to convince the so-called swing states that leaving the public core alone is in the interest of all states. Also, private parties must explicit be made part of the diplomatic effort regarding internet governance. Considering the great power of internet giants such as Google and Apple, governments can no longer ignore these parties in diplomatic sense. These companies are more than possible investors or privacy violators: they are parties that need serious diplomatic attention because of their crucial role in digital life, with all the contradictions that come with diplomacy. And lastly, the expertise of NGOs and other private parties must be made productive, without creating false expectations about their role in the administration of the internet. A lot can be whole here, especially regarding thinking about the consequences of internet governance for the technical functioning of the internet as a whole.

Related:

- 2014-12-30: Dutch Advisory Council on International Affairs (AIV) advises on internet freedom

- 2015-03-20: concerning “interference”, also see Open Right Group’s submission to the UK Home Office consultation for the Draft Equipment Interference Code of Practice.

EOF