Intelligence Support Systems (2005) by Paul Hoffmann (telecom expert; Germany) and Kornel Terplan (telecom expert; U.S.) is by far the best technically in-depth book on Lawful Interception (LI) in existence. It’s an expensive book, but used copies can be found that are more affordable (I bought one of those). In the remainder of this post I quote a selection of paragraphs from the following Chapters:

- Chapter 1: Setting the Stage

- Chapter 5: Extended Functions for Lawful Intercepts

- Chapter 10: Outsourcing Lawful Interception Functions

The term “intelligence support systems” (ISSs) is used throughout the text below, and is explained as follows in the book’s preface:

Intelligence support systems (ISSs), the focus of this book, are about intelligence as opposed to security. Security involves providing firewalls, anti-virus protection, and intrusion detection and prevention; in other words, security is about guarding against loss. Conversely, in ISS, information is gathered about illegal activities, and that knowledge is applied to increasing security where applicable. ISSs interface with, or are part of, billing, ordering, provisioning, and authenticating systems, as well as law enforcement systems.

The concepts, technology and issues presented in the book are varyingly relevant to the US, EU and beyond.

Chapter 1. Setting the Stage

[…]

The focus of intelligence support systems (ISSs) is on expanded infrastructure requirements of telecommunications service providers (TSPs), which are basically no different from the requirements of operations support systems (OSSs) and business support systems (BSSs). Intelligence plays two principal roles in this area. On one hand, it provides surveillance by collecting information on illegal activities, such as terrorism, criminal activities, fraud, and money laundering, and on the other hand, it provides the basic data that improve the bottom line of TSPs, such as revenue assurance, business intelligence (BI), and protection against telecommunications fraud. In short, ISSs are software elements or units that interface with, or are subsumed under, billing and ordering systems, provisioning and authentication systems, and outside parties such as law enforcement agencies (LEAs) (Lucas, 2003f).

TSP will be used as a generic term throughout the book for a number of different service providers, including access providers, network operators, communications service providers, electronic communications service providers, and licensed telecommunications service operators. Terms differ according to the standards for lawful interception of different countries and different LEAs.

1.1 Positioning Lawful Intercepts (LIs) and Surveillance

Information and intelligence must be differentiated from each other. Information in the context of surveillance consists of knowledge, data, objects, events, or facts that are sought or observed. It is the raw material from which intelligence is derived (Petersen, 2001).

Intelligence is information that has been processed and assessed within a given context, and it comprises many categories (Petersen, 2001). In the context of this book, communications intelligence — derived from communications that are intercepted or derived by an agent other than the expected or intended recipient or are not known by the sender to be of significance if overheard or intercepted — is the key focus. Oral or written communications, whether traditional or electronic, are the most common form of surveillance for communications intelligence, but such intelligence may broadly include letters, radio transmissions, e-mail, phone conversations, face-to-face communications, semaphore, and sign language. In practice, the original data that forms a body of communications intelligence may or may not reach the intended recipient. Data may be intercepted, it may reach the recipient at a date later than intended, or it may be intercepted, changed, and then forwarded onward. However, the process of relaying delayed or changed information is not part of the definition of communications intelligence; rather, the focus is on intelligence that can be derived from detecting, locating, processing, decrypting, translating, or interpreting information in a social, economic, defense, or other context (Petersen, 2001).

Information collection is usually used to support surveillance activities. Surveillance is defined as keeping watch over someone or something, and technological surveillance is the use of technological techniques or devices to aid in detecting attributes, activities, people, trends, or events (Petersen, 2001). Three typical types of surveillance are relevant to LIs:

- Covert surveillance: surveillance that is not intended to be known to the target. Covert wiretaps, hidden cameras, cell phone intercepts, and unauthorized snooping in drawers or correspondence are examples. Most covert surveillance is unlawful; special permission, a warrant, or other authorization is required for its execution. Covert surveillance is commonly used in law enforcement, espionage, and unlawful activities.

- Overt surveillance: surveillance in which the target has been informed of the nature and the scope of the surveillance activities.

- Clandestine surveillance: Surveillance in which the surveilling system or its functioning is not hidden but also is not obvious to the target.

Finally, there are various categories of surveillance devices (Petersen, 2001): (1) acoustic (audio, infra and ultrasound, and sonar), (2) electromagnetic (radio, infrared, visible, ultraviolet, x-ray), (3) biochemical (chemical, biological, and biometric), and (4) miscellaneous (magnetic, cryptologic, and computer). In different contexts, including some of those described in this book, a combination of such devices might be used (e.g., a combination of acoustic, electromagnetic, and miscellaneous devices). Appropriate chapters will clearly highlight the technologies and devices in use.

1.2 ISS Basics and Application Areas

[…]

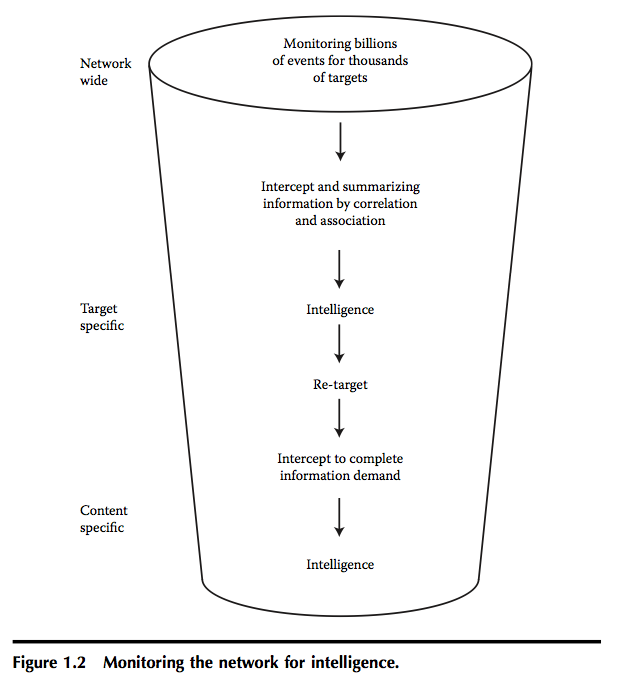

As indicated in Figure 1.2, there are three different types of intelligence (Cohen, 2003):

- Summary intelligence: An ISS that provides this level of information needs to capture all key summary data in a manner that is lawful and protects the rights of individuals. For instance, an ISS may be programmed to capture information on everyone who visits a particular suspect Web site without capturing individual names. The ISS may then take this information and see if any of the IPs visiting this Web site have also been communicating via e-mail or chatting with another known target. If so, a legal authorization may be obtained to look at the individual in question in more detail.

- Target intelligence: Once a target has been identified on the basis of summary intelligence or other information sources and lawful authorization has been received, it may be necessary to look at any and all of that particular individual’s communications on all networks, including e-mail, Web sites visited, chatting, instant messaging, short message service (SMS), and multimedia messaging service (MMS) mobile phone messages, Voice-over-IP (VoIP) broadband connection calls, and so forth. Specific details can then be obtained from this information.

- Content intelligence: Content intelligence may be needed to lawfully review specific content, for example, all e-mail communications of the target. The ISS should make it possible to look at this detailed content information in all forms (e.g., e-mail, VoIP, Web site replay, and chatting replay).

[…]

1.6 Framework of LIs

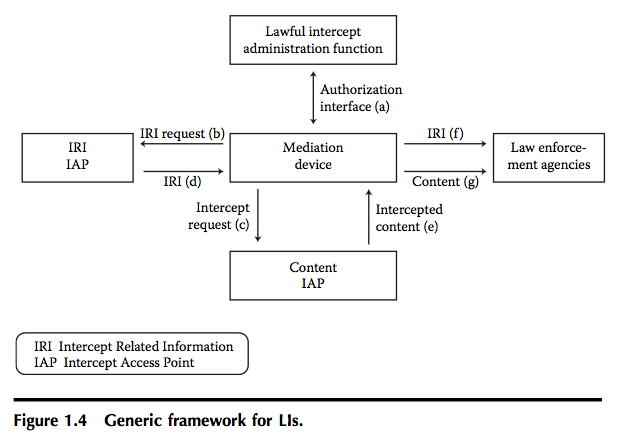

Figure 1.4 shows a generic framework of LIs (Baker, 2003) derived from a draft model commissioned by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). This draft streamlines principal functions, components, and key players. This generic framework shows a high level of compliance with North American and European standards regarding lawful interception.

Several entities are included in this LI model:

- LI administration function: This function provides the provisioning interface for the intercept stemming from a written request by an LEA. It can involve separate provisioning interfaces for several components of the network. Because of the requirement to limit accessibility to authorized personnel, as well as the requirement that LEAs not be aware of each other, this interface must be strictly controlled. The personnel who provide the intercepts are especially authorized to do so and are often employed directly or indirectly by the TSPs whose facilities are being tapped. In many cases, the identity of the subject received from the LEA has to be translated to one that can be used by the networking infrastructure to enable the intercept.

- Intercept access point (IAP): An IAP is a device within the network that is used for intercepting lawfully authorized information. It may be an existing device with intercept capability (e.g., a switch or router), or it may be a special device (e.g., a probe) provided for that purpose. Two types of IAPs are considered here: those providing IRI and those providing content information.

- IRI IAP: This type of IAP is used to provide IRI, that is, information related to the traffic of interest. There is currently no standardized definition of IRI for IP traffic. IRI is the collection of information or data associated with telecommunications services involving target identity, specifically communication-associated information or data (e.g., unsuccessful communication attempts), service-associated information or data (e.g., service profile management), and location information.

- Content IAP: A content IAP is one that is used to intercept the traffic of interest.

- LEA: The agency requesting the intercept and to which the TSP delivers the information.

- Mediation device (MD): These devices receive the data from the IAP, package it in the correct format, correlate them with LI warrants, and deliver it to the LEA. In cases in which multiple LEAs are intercepting the same subject, the MD may replicate the information multiple times.

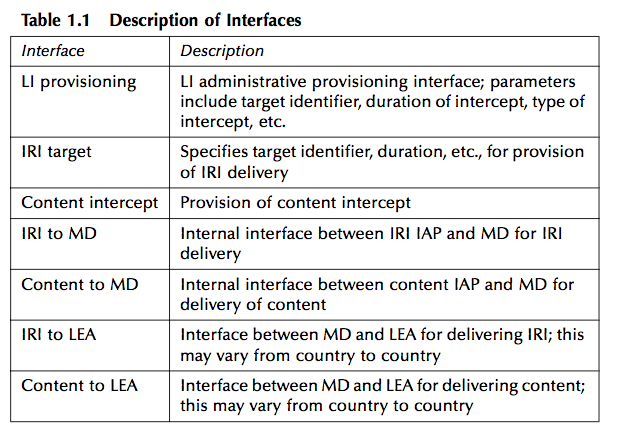

This generic reference model contains a number of interfaces, as can be seen in Table 1.1, and it can be deployed in many different ways. More details are presented in Chapter 3.

[…]

1.7 Challenges

Supporting lawful interception in various geographical areas is not without challenges. This concluding section concentrates on technical, economical, and privacy challenges due to lawful interception.

[…]

In summary, the technical challenges relating to ISSs are as follows:

- Enormous volumes of dispersed data:

- Data volumes of various services are much higher than with voice-related data.

- Data throughout the networks (not just at the device) must be correlated.

- Data can be missed or lost because of these huge volumes.

- Data is too voluminous to be stored in a database without real-time processing and reduction of data.

- Need for real-time data:

- Dispersed data requires real-time processing and correlation to produce information.

- Network speeds make it difficult to capture and process information in real-time.

[…]

In summary, the following are the economic challenges associated with ISSs:

- Costs of point solutions for intercepts are high.

- Scalability is not guaranteed.

- Necessary skills and procedures are lacking.

- It is difficult to guarantee ROI with surveillance only.

- Using existing technology with modifications for surveillance seems to be a viable option, but its cost justification is still difficult to support with hard numbers.

[…]

In summary, privacy challenges relating to ISSs are as follows:

- Legal rules differ in different countries.

- Technological issues are different for voice and data networks.

- Current technology does not support LIs and privacy laws simultaneously.

[…]

5. Extended Functions for Lawful Intercepts

[…]

5.3 Handover Interfaces (HIs)

[…]

5.3.2 Handover Protocols

[…]

IPDR Streaming Protocol is a new, reliable, real-time protocol that (1) leverages IPDR foundations, (2) uses XDR-based compact binary encoding and TCP/IP transport, (3) is applicable to a broad set of services and domains, and (4) is specifically designed to address requirements for data exchange applicable to the area of LIs. The attributes of this protocol are its reliability, flexibility, efficiency, and manageability; the fact that it provides real-time streaming; and the fact that it leverages overall IPDR technology benefits.

5.3.2.1 Reliability

Why is reliability important?

- Support of critical applications

- Avoidance, through high availability, of additional availability costs

- Compliance with regulatory requirements

How can reliability be increased?

- Use of data-capturing systems that provide scalable availability

- Use of application-level acknowledgment for information exchange

- Use of reliable transport, such as TCP/IP

- Use of built-in fallover and fallback mechanisms

- Use of redundant probes and hot standby support

- Use of cost-effective deduplication mechanism

- Use of tunable keep-alive messages

5.3.2.2 Flexibility

Why is flexibility important?

- All services are supported, including emergency services

- Reductions in proliferation of other surveillance-related protocols

- Support of a wide range of LI models

- Support of a variety of OSSs/BSSs, including billing, fraud, performance management, and fault management

- Investment protection

How can flexibility be increased?

- Use of readable XML schema definitions of record structures

- Negotiation of upgrades (“future-friendly”)

- Specified transformations to and from XML or XDR IPDR files

5.3.2.3 Efficiency

Why is efficiency important?

- Minimizes effects on network and service elements, on the network itself, and on data-capturing systems

- Reduces costs

- Allows large amounts of data to be handled

How can efficiency be increased?

- Compute and export only the data requested by collectors (e.g., LEAs)

- Export data only with collector subscription

- Use entire bandwidth via windowed application-level acknowledgment

- Minimize fall-over times by keeping hot standby ready with “keep-alives”

- Compact (XDR) data representation

5.3.2.4 Manageability

Why is manageability important?

- Supports a global, heterogeneous environment

- Supports plug-and-play for large multivendor deployments

How can manageability be increased?

- Built-in negotiation of protocol version, data capturer and exporter capabilities, templates, and fields

- Support by exporter and collector of one or multiple versions of protocols

- Use of back-end-friendly interfaces

5.3.2.5 Real-Time Streaming

Why is real-time streaming important?

- Allows hot surveillance-related applications

- Allows real-time reaction to activity (e.g., target identification, fraud, and security breaches)

- Supports other real-time applications

How can real-time streaming be implemented?

- Immediate transmission of intercepted data with minimal latency and avoidance of periodic batch closes

- Continuous stream of events sent from IAPs

- Presence of hot backup allowing a secondary option to receive data in the case of configurably defined criteria

5.3.2.6 Leverage of Overall IPDR Technology Benefits

IPDR technology benefits are leveraged via the following:

- Use of information model-based service descriptions, applicable regardless of encoding or transport method

- Availability of open source implementations without the need to pay royalties

- Uniform applicability in network data collection

- Open standards-based format

- Availability of certified products

The IPDR protocol is broadly applicable to Voice-over-IP (VoIP), CPEs, data over cable, media and application servers, and traffic analyzers.

[…]

5.7 Receiver Applications

[…]

5.7.1 Support for Recognizing Criminal Activities

5.7.1.1 Search for Criminal Activities

This area falls under strategic surveillance owing to the fact that there are no specific targets at the initiation of the process. Observation of communication directions and paths, and evaluation of the contents of various applications, may help narrow lists of potential targets. However, large amounts of data must be evaluated, filtered, analyzed, sorted, classified, and selected to reach conclusions regarding individuals, groups, locations, or suspect activities.

5.7.1.2 Communication Analysis

Collection of actionable intelligence requires in-depth analysis of communication activities. This process involves correlation of time stamps, locations, communication relationships, authentications, directions, and communications forms and volumes. Location tracking, geographical information systems, and data mining are some of the methods under consideration to support such analyses.

5.7.1.3 Content Analysis

In-depth analysis of communicated content is necessary as well. This involves analyzing and correlating application identifications, language recognition, speaker recognition and identification, word spotting, topic recognition, optical character recognition, logo recognition, and image recognition. Both text-based and audio-based analyses are frequently used.

5.7.1.4 Automated Intelligence Support

Content is created from text- and audio-based documentation elements. Results are generated by combining and correlating multiple inputs, including faxes, TIFF files, image files, eDoc files, HTTP, e-mail, chat, and sound files. Figure 5.10 shows an example of such a combination and correlation (Axland, 2004). In a further step, languages and speakers may be recognized by using combined forms of intelligence.

[…]

10. Outsourcing Lawful Interception Functions

[…]

10.1 Forces Driving Outsourcing

Several principal forces drive the outsourcing of LI functions (Warren, 2003b):

- In-house provisioning, administration, and security surveillance have become too expensive; in particular, personnel costs are increasing rapidly.

- There is a chronic shortage of skilled personnel.

- TSPs must comply with LEA requirements, and legal interpretations must be clear and quick in today’s changing legal environment.

- Supporting LIs in-house may result in a loss of focus on strategic issues that help increase revenue and generate profit.

- Service expectations may be defined and supervised more effectively with an outsourcer than in the case of an insourced solution.

TSPs must contend with several other issues as well:

- Technology has simplified access to network elements and information.

- LEAs are now demanding access to digital storage of customer-related information.

- LEAs are demanding Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) and ETSI compliance.

- Most ISPs do not have the personnel or business support systems (BSSs) in place to handle broad record production searches and electronic surveillance demands.

Another important factor to consider is the increasing personnel burden and high costs involved in support of LEAs’ demands for records and technical assistance. For example, growing workloads increase the potential for mistakes. Also, as workloads increase and backlogs grow, there are greater legal risks stemming from the possibility of errors, thus potentially leading to greater risk of damage to a TSP’s public image.

Finally, in terms of business challenges, more is being demanded of TSPs, and business realities show that the LI function is not a revenue-generating one. In addition, today’s economic conditions require cost reductions on the part of TSPs. TSPs must weigh two fundamental options:

- Building an internal infrastructure: obtaining legal assistance in developing policies and procedures, hiring and training personnel with expertise in legal matters, implementing compliance programs and audit procedures, and investing in technology to support operations

- Outsourcing surveillance-related activities: using an outside law firm for deploying policies and procedures and implementing an end-to-end solution with a service bureau

Before deciding for or against outsourcing, TSPs should carefully evaluate the following criteria:

- Present or expected end-to-end costs of supporting LIs: All effects should be quantified in terms of both capital and operational expenses.

- Efficiency of existing processes, tools, and human resources: This area is essential in determining which functions, if any, to outsource.

- Extent of dependence on speed: The real-time requests of LEAs must be met.

- Grade of service and applications required: These needs may dictate the type of outsourcing used.

- Level of security for the handover interface (HI) between SPs and LEAs.

- Cost effectiveness: Is it more cost-effective to concentrate on the provider’s core business than to build a full infrastructure to support lawful interception.

- Capital investment required: If the company must invest substantial amounts in lawful interception, it should favor outsourcing; if not, outsourcing may still be considered but should receive lower priority.

- Current and future need for skilled personnel: The most sophisticated LI technology will be useless if the company cannot find employees to run it.

- Potential acquisitions, mergers, sales of business units, as well as changes in service portfolio: These elements should be carefully evaluated, given that each may affect contracts with outsourcers.

- Whether it is possible to negotiate acceptable outsourcing contracts: Contract terms are of paramount importance considering the long durations of contracts in this sensitive area.

- Careful evaluation: Determination of all services and functions offered by the outsourcer, as well as knowledge levels and experience.

- Careful review of the proposed transitioning warranty: This must be done on behalf of the outsourcer.

10.2 The LEA Model

In this case, LEAs take full responsibility for all principal functions. If required, they initiate all necessary processes including on-the-fly provisioning of networking equipment and facilities. TSPs are expected to provide physical access to equipment and facilities. Occasionally, the physical presence of subject matter experts of TSPs is required during surveillance.

In addition to obvious benefits in the area of legal expertise, benefits of this model are LEAs’ extensive knowledge regarding the targets of and reasons for surveillance, their high motivation to prosecute criminals, and the possibility of enhanced collection results. Disadvantages included limited technical know-how in regard to networking technologies, the limited (and most likely obsolete) surveillance tools available, lack of experience with the access and delivery functions (AF and DF), and shortages in terms of human resources.

10.3 The ASP Model

In this case, application service providers (ASPs) take full responsibility for providing the application software necessary to support all principal surveillance functions. ASPs are represented by TSPs or third parties. Benefits of this model include the following:

- Good scalability of solutions

- Usage-based billing

- Lower number of personnel required

- Flexibility in instances in which networking technology changes are required

Disadvantages include:

- Security risks due to shared applications

- Dependence on the ASP

- Contractual risks

- Limited legal background of the ASP

10.4 The Service Bureau Model

The requirements associated with this model can be summarized as follows:

- The service bureau must provide comprehensive record production.

- It must adhere to professional legal and service standards.

- It must support effective coordination with LEAs.

- It should provide technology that is trusted by both SPs and LEAs.

- It must ensure high scalability for increasing data volumes.

- It must minimize legal risks in both civil and criminal terms.

- It must protect the public image of the SP.

- It must represent a cost-effective alternative to an SP internal structure.

- It is expected to be staffed by subject domain experts with extensive field experience.

The benefits of the service bureau model are:

- Focus on core business opportunities

- Reductions in operating costs

- Conservation of capital; risk and up-front investments in personnel and surveillance technology assumed by service bureau

- Support of future-proof services

- No concern about operations for TSPs

Disadvantages include:

- Legal dependency on outsourcer

- Technological dependency on outsourcer

- Security risks with HI

- Possible internal resistance

- Potential loss of subject matter experts

- Need for minimal (critical) mass of staff as backup

- Need for continuous supervision of contracts

- Possible lack of cost savings

- Transitional problems

- Risk of losing control over LI-related information

- Risk of outsourcer not representing the interests of the SP

Supporting the Service Bureau Model, Trusted Third Parties (TTP) are gaining a lot of attention these days.

The value proposition of TTP includes the following items:

- Independence is key to trust by enhancing privacy with Calea and Etsi

- TTP has freedom to employ a range of architectures, such as internal, external, and adjunct

- TTP can generally follow safe harbor standards

- TTP offers value-added services, such as authentication of trust systems, legal analysis and verification of orders, proof of performance, and subpoena processing

Comparing costs, outsourcing most likely outperforms self-deployment of lawful intercept technologies from year one.

Outsourcing of lawful intercept in service bureau form offers the following additional values to LEAs and TSPs:

- Reduces operations expenses including staffing needs

- Minimizes capital expenditures for future network services

- Minimizes LEA-related network interference

- Alleviates risk of stranded investment in rapidly changing network infrastructure

- Most cost-effective way to meet LEA needs at the right time

- Faster time to market, easier entrance to new markets, generates compliance rapidly

- Allows carriers to focus on their core business

Table 10.1 shows options in the functions for outsourcing supporting LI activities.

Outsourcers should be rated according to the following criteria, among others:

- Financial strength and stability over a long period

- Excellent security record and clearance for highly sensitive assignments

- Outstanding business reputation

- Outstanding legal background

- Demonstrated ability to support lawful interceptions

- Number of employees, along with their clearance level and level of experience in supporting lawful interception

- History of using and implementing state-of-the-art technology, frameworks, and tools

- Ability to customize tools to networking technologies

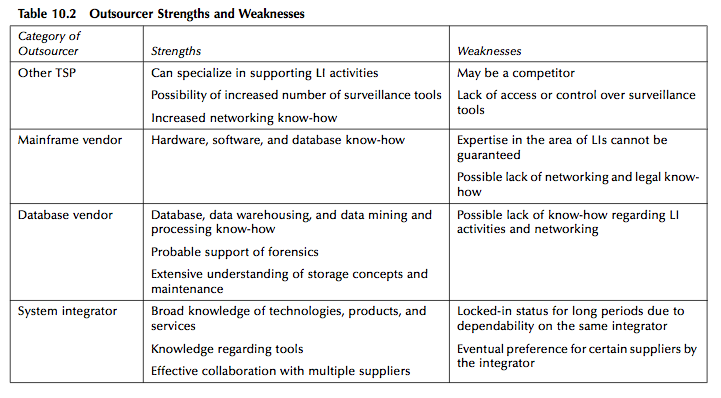

The strengths and weaknesses of each category of outsourcers are summarized in Table 10.2.

[…]

10.6 Who Are the Principal Players?

Because of the sensitivity of LIs, participating entities are careful about sharing responsibilities with external companies. As a result, outsourcing trends are not yet visible. If they so desire, professional outsourcers in the telecommunications field can extend their services toward LI activities. Also, outsourcers from the legal side can offer services in regard to at least the collection function. This section considers a few early examples of outsourcing options:

- LEAs: Typical example is the FBI in the United States

- ASPs: Forensics Explorer

- Service bureau providers: VeriSign

- LI-monitoring centers: Siemens solution with a number of add-on functions, in cooperation with GTEN, Datakom, and Utimaco System integrators: VeriSign and GTEN

- Consulting companies: Neustar/Fiducianet, Inc., in the United States

It is expected that this short list will grow rapidly in the near future.

[…]

EOF