UPDATE 2015-11-14: de lijst van updates/actualiteiten is naar de bodem verplaatst.

De NCTV-website polarisatie-radicalisering.nl [archiefkopie hier] bevat “kennis en ervaring van vijf jaar beleid op het terrein van polarisatie en radicalisering”, bestaande uit een uitgebreid handelingskader [archiefkopie hier] voor wie met radicalisering te maken krijgt, en tientallen praktijkvoorbeelden [archiefkopie hier]. In deze post citeer ik een aantal fragmenten uit die informatie met het doel een weergave te geven van het preventieve gedeelte van de praktijkaanpak van radicalisering in Nederland (dus niet het repressieve: oppakken, uitreisverbod, nationaliteit afpakken, etc.). Het onderstaande leeft voort onder de door het kabinet in augustus 2014 aangekondigde versterkte integrale aanpak jihadisme en radicalisering (.pdf) (actiepunten 21 t/m 28).

Context, verdieping en verbreding kan worden gevonden via de links, of via het lijstje bij “Verder leesvoer” onderaan. Niemand pretendeert volledigheid of perfectie in de aanpak van radicalisering; daar is de menselijke wereld te complex voor.

Terug naar die NCTV-website. Het handelingskader beschrijft wat men kan doen indien geconfronteerd met polarisatie en (mogelijke) radicalisering. Nuansa (MinVenJ) en het Nederlands Jeugd Instituut schreven voor instellingen in onderwijs, jeugdzorg en welzijn de Handreiking radicalisering en polarisatie (.pdf, 2012). Fragmenten uit die handreiking staan in het handelingskader; ook is de handreiking terug te vinden in de toolbox extremisme, opgesplitst in tien ‘servicedocumenten’.

De handreiking bevat het volgende vraag-aanbod model ter illustratie van factoren die een rol spelen bij radicalisering:

In de handreiking wordt het model als volgt toegelicht (in vrij informele stijl):

- Vragen (geel): De jongere of jongvolwassen gaat opzoek naar zijn of haar identiteit: wie ben ik? Waar hoor ik bij? Wat moet ik doen? In contact met ouders, familie, vrienden, school etc. worden deze vragen beantwoordt. Hierdoor vindt identiteitsvorming plaats.

- Aanbod (oranje): Onderdeel van het aanbod aan antwoorden voor de identiteitsvorming kunnen ook radicale ideologieën zijn. Deze idealen en ideologieën kunnen aan jongeren en jongvolwassen op verschillende manieren worden aangeboden. Het internet is de meest uitgebreide en toegankelijke vindplaats van dit aanbod, maar ook door flyers, op het schoolplein en tijdens bezoeken aan de moskee kunnen jongeren en jongvolwassenen in aanraking komen met radicale ideeën.

- Voedingsbodem (groen): De voedingsbodem welke de aantrekkingskracht van radicale ideeën genereert bestaat uit:

- Gevoelens van achterstelling, discriminatie, vernedering of uitsluiting en het ervaren van onrecht. Deze gevoelens kunnen voortkomen uit eigen persoonlijke ervaringen maar kunnen ook voortvloeien uit vermeende ervaringen of gebeurtenissen in de media. Ook de integratieparadox speelt een rol: hoe meer migranten gericht zijn op de Nederlandse maatschappij en willen integreren, hoe groter hun verwachtingen worden ten aanzien van de maatschappij en hoe gevoeliger ze zijn voor cultuurconflicten en uitsluiting.

- Persoonlijke gebeurtenissen in het leven van een jongere of jongvolwassene waardoor ze onzeker worden over wie ze zijn. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn een scheiding van ouders, het verlies van een dierbare of een waardevolle vriendschap.

- Psychische problematiek (blauw): De laatste jaren tonen diverse onderzoeken aan dat personen met een psychische problematiek, zoals autisme, gevoeliger kunnen zijn voor radicale ideeën. Door psychische problemen kunnen ze verminderd in staat zijn gevoelens te tonen of empathie te tonen voor andersdenkenden.

- Cognitieve opening (rood): de combinatie van de aantrekkingskracht van een ideologie of gedachtegoed en de voedingsbodem bij het individu waardoor het proces van radicalisering kan worden verklaard.

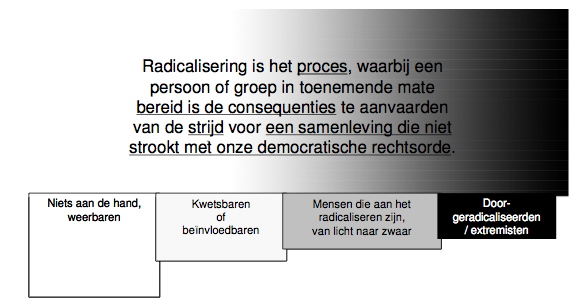

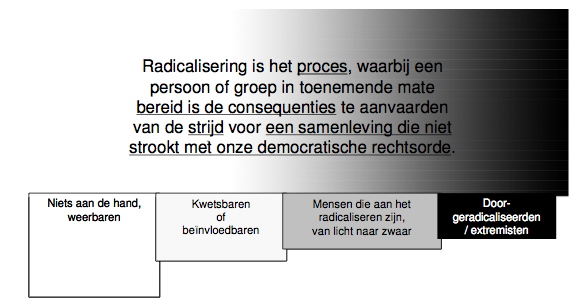

Vervolgens wordt het radicaliseringsproces als volgt geduid:

Zoals gezegd is radicalisering een proces; dat verloopt niet volgens een vast stramien. De te onderscheiden groepen, zoals hieronder weergegeven, overlappen elkaar. Het is daarbij niet gezegd dat als je links begint met stappen te zetten, je uiterst rechts eindigt. Het proces kan razend snel of juist langzaam gaan, stilvallen en weer terugtreden. Voor de meeste personen die een proces van radicalisering doormaken betekent het verkrijgen van regelmaat, structuur en verantwoordelijkheden (‘ huisje, boompje, beestje’) de doorloop naar de-radicalisering.

Daarbij wordt gesteld:

De eerstelijnsprofessional [=persoon werkzaam in onderwijs, jeugdzorg of welzijn] zal zelden of nooit met de uiterst rechtse fase te maken hebben. Interveniëren bij deze groep is veelal voorbehouden aan de politie, AIVD of de-radicaliseringsdeskundigen. Vooral de eerste twee fasen zijn voor de professional de grootste uitdaging om jongeren weerbaar te houden of te maken zodat ze niet meer beïnvloedbaar zijn of kunnen worden. De professional kan vanuit de zorg voor en betrokkenheid op de jongere een bijdrage leveren aan het tegengaan van radicalisering.

Over specifieke signalen waaraan radicalisering kan worden herkend wordt het volgende gesteld:

Hieronder volgt een handreiking bij het herkennen en duiden van radicalisering door:

- het verhelderen van signalen die mogelijk een aanwijzing kunnen zijn voor (dreigende) radicalisering;

- het stellen van controlevragen;

- het weten op te sporen van bedreigende factoren of omstandigheden, die de situatie zorgelijker zouden kunnen maken.

vooraf

Belangrijk voorafgaande aan gebruik van deze lijst is:

- Doe de duiding niet alleen: zoek contact met andere professionals, ouders of vrienden van de persoon waar u zich zorgen over maakt. Inventariseer of uw zorg gedeeld wordt, wat ervaren of zien zij?

- Pas op voor overhaaste, onterechte labels. Stel jezelf controlevragen.

- Ook als er geen sprake is van (dreigende) radicalisering kan een ‘niet-pluis-gevoel’ en een aantal signalen duiden op een zorgelijke situatie waarin iets moet gebeuren – ook als het niets met radicalisering te maken heeft.

ad 1. de signalen

Bij personen die in een proces van radicalisering zitten is vaak een aantal van de volgende mogelijke signalen van radicalisering te onderscheiden:

- Vervreemding en (zelf)uitsluiting: afstand nemen, persoonlijke relaties veranderen drastisch en contacten worden verbroken.

- Devotie en idealisme: verheerlijking van idealen, een ideale samenleving en het verlaten van instituties die deze idealen niet delen. Waar loopt hij of zij warm voor?

- Bedreigingen en vijanden: benoemen van bedreigingen van ‘de vijand’. Waar is hij of zij tegen of bang voor?

- Privaat is publiek: er wordt geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen private normen en de publieke normen.

- Uiterlijke kenmerken en andere uitingsvormen: kleding, profielsite en alias dienen niet om hip te zijn, maar hebben een ideologisch statement.

- Onderlinge loyaliteit: de gedeelde ideologie of groepsidentiteit wordt belangrijk. Radicalisering is vaak een sociaal proces, een soort van ‘nieuwe familie’. Uitzondering hierop zijn eenlingen welke radicaliseren binnen een (zelfverkozen) isolement.

- Actiebereidheid: Is het onrecht of de bedreigingen dusdanig dat de persoon voelt dat hij tot actie moet overgaan en zijn bijdrage aan de ‘strijd’ wil/moet leveren? Wordt geweld daarbij gerechtvaardigd of acties gelegitimeerd?

ad 2: controlevragen

Belangrijk is om als professional controlevragen te stellen:

- Kan het gaan om handelingen die lijken op radicale uitingen maar ook op iets anders kunnen duiden?

- Kan het gaan om radicale symbolen, leuzen en redeneringen die worden geuit zonder dat dit gedachtegoed of de ideologie ook wordt gedeeld?

- In hoeverre is er sprake van een ideologisch component? Of worden bepaalde argumentaties enkel provocerend gebruikt?

- Is het de eerste keer dat je dit gedrag of uiting waarneemt of heb je al eerdere, vergelijkbare ervaringen opgedaan? Is er sprake van gedragsverandering bij de persoon in kwestie?

- Ben jij de enige die ziet dat er sprake is van (geen) radicalisering, of kijken je collega’s en professionals van andere instellingen die de jongere kennen, er ook zo tegen aan?

- Hoe verhoudt het waargenomen gedrag zich tot het aangehangen gedachtegoed? In welke mate beïnvloedt het denken het doen?

ad 3: bedreigende factoren

Naast de signalenlijst en bij behorende controlevragen kunnen bedreigende factoren rond het individu in kwestie – ook wel voedingsbodem genoemd- tevens de zorgelijkheid van signalen doen toenemen:

- slecht sociaal netwerk, isolatie of vervreemding;

- problematische identiteitsontwikkeling (bijv. eenzaamheid, gepest worden etc.);

- aanwezigheid van radicale personen in de directe omgeving;

- persoonlijke crises (bijv. scheiding, ontslag, conflicten en crises);

- frustrerende gebeurtenissen (bijv. integratieparadox) ;

- persoonlijke gebeurtenissen die leiden tot schaamte/schande;

- slechte schoolprestaties, werkloosheid, slechte arbeidsmarktkansen;

- psychische problematiek;

- drank en drugs.

(Nota bene: er wordt gewaarschuwd geen “overhaaste, onterechte labels” te plakken, maar tegelijkertijd wordt aanbevolen iets te signaleren als er sprake is van een “niet-pluis-gevoel”. Het zal een blijvend aandachtspunt zijn: onder welke omstandigheden wordt iemand wel of niet in beeld gebracht, en met welke duiding? Bij de politie, of, al dan niet via de CT-Infobox, de AIVD? Daarbij zijn vervolgvragen te stellen: welke gevolgen heeft de labeling voor de betrokkene en diens sociale omgeving? En: worden persoonsgegevens bij gebleken onterechte registratie, of na succesvolle deradicalisatie, uit alle hoeken en gaten van de betrokken informatiesystemen gewist, of duikt informatie — al dan niet met context — in de toekomst weer op wanneer betrokkene een VOG of VGB nodig heeft, of een uitkering aanvraagt? Fout-positieven zijn denkbaar: pubers of adolescenten die niet worden ‘afgevangen’ door controlevragen of peer review, maar waarbij in werkelijkheid geen sprake is van een dreiging.)

Voor het registreren van radicalisering van personen t/m 22 jaar oud, kunnen gemeenten met een beroep op artikel 7.1.4.1 van de Jeugdwet zonder toestemming van betrokkene een melding plaatsen in de Verwijsindex Risicojongeren (Vir). Vereiste is dan dat de meldingsbevoegde (de gemeente) een redelijk vermoeden heeft dat “de jeugdige door een of meer van de hierna genoemde risico’s in de noodzakelijke condities voor een gezonde en veilige ontwikkeling naar volwassenheid daadwerkelijk wordt bedreigd”:

- de jeugdige staat bloot aan geestelijk, lichamelijk of seksueel geweld, enige andere vernederende behandeling, of verwaarlozing;

- de jeugdige heeft meer of andere dan bij zijn leeftijd normaliter voorkomende psychische problemen, waaronder verslaving aan alcohol, drugs of kansspelen;

- de jeugdige heeft meer dan bij zijn leeftijd normaliter voorkomende ernstige opgroei- of opvoedingsproblemen;

- de jeugdige is minderjarig en moeder of zwanger;

- de jeugdige verzuimt veelvuldig van school of andere onderwijsinstelling, dan wel verlaat die voortijdig of dreigt die voortijdig te verlaten;

- de jeugdige is niet gemotiveerd om door legale arbeid in zijn levensonderhoud te voorzien;

- de jeugdige heeft meer of andere dan bij zijn leeftijd normaliter voorkomende financiële problemen;

- de jeugdige heeft geen vaste woon- of verblijfplaats;

- de jeugdige is een gevaar voor anderen door lichamelijk of geestelijk geweld of ander intimiderend gedrag;

- de jeugdige laat zich in met activiteiten die strafbaar zijn gesteld;

- de ouders of andere verzorgers van de jeugdige schieten ernstig tekort in de verzorging of opvoeding van de jeugdige, of

- de jeugdige staat bloot aan risico’s die in bepaalde etnische groepen onevenredig vaak voorkomen.

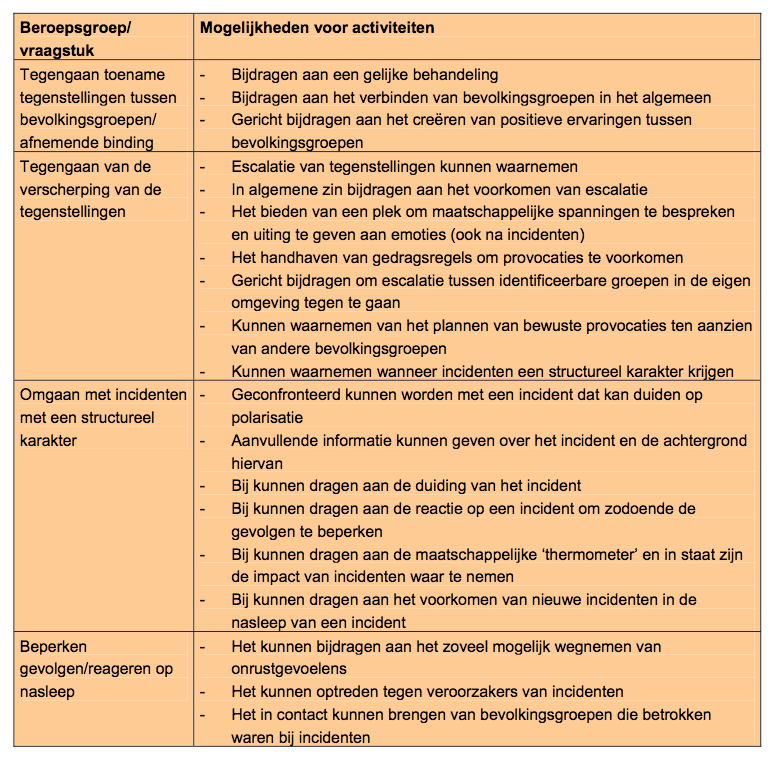

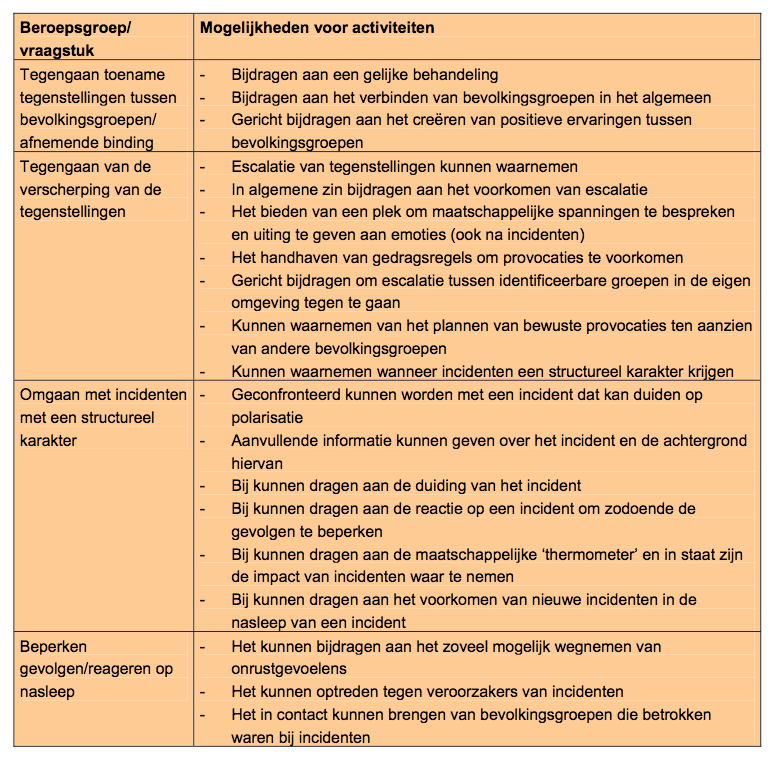

Voor wat betreft polarisatie geeft de handreiking het volgende handelingsperspectief, afkomstig uit de publicatie De rol van eerstelijnswerkers bij het tegengaan van polarisatie en radicalisering (.pdf, 2008) van COT, het Instituut voor Veiligheids- en Crisismanagement:

Volgens COT kan deze tabel “als handvat dienen bij het doordenken van de rol van de eerstelijnswerker”. In de COT-publicatie worden vervolgens mogelijke rollen uitgewerkt voor gemeenten, politie, justitie, onderwijs, welzijnswerk en jeugdhulpverlening. Daarbij is ook gekeken naar de beperkingen en mogelijkheden die per rol (dus: per context) bestaan ten aanzien van bijdrage aan het voorkomen van radicalisering.

Voor al het bovenstaande geldt dat effectiviteit zich lastig laat meten: er zijn veel variabelen en er kan moeilijk met controlegroepen worden gewerkt. Causale verbanden vaststellen is dan moeilijk — je weet bijvoorbeeld niet of personen die niet radicaliseren, zonder deze maatregelen wél zouden zijn geradicaliseerd. Er is wel anecdotaal bewijs: de praktijkvoorbeelden die zijn gedeeld. En men zou kunnen stellen dat het voor de uitkomst niet uitmaakt: minder radicalisering is minder radicalisering, en wie weet is een gedeelte van de uitkomst daadwerkelijk het gevolg van de geleverde inspanningen, niet alleen van veranderingen elders in de wereld.

Verder leesvoer:

- Toolbox extremisme (NCTV) + besluit Wob-verzoek (nov 2015; 750+ pagina’s)

- Actieplan Integrale Aanpak Jihadisme (.pdf, Rijksoverheid, 2014-08-29)

- Handreiking democratisch weerwoord. Deel 1 Praktijkboek (.pdf, COT, 2013)

- Handreiking democratisch weerwoord. Deel 2 Verdieping (.pdf, COT, 2013)

- Handreiking deradicalisering (.pdf, 2013)

- Terrorismebestrijding en mensenrechten: het SECILE-project (dit blog, 2014-01-25)

- Why We Can’t Just Read English Newspapers to Understand Terrorism (Kalev Leetaru in Foreign Policy, 2015-04-15)

- Radicx – Vroegtijdige signalering van radicalisering (.pdf, APS / KPC Groep, 2010)

- Radicalisation Awareness Network (Radar Advies iov Europese Commissie, 2012-2016)

- CoPPRa: Community policing preventing radicalisation & terrorism (EU-project; 2010-2013)

- SAFIRE: Scientific Approach to Finding Indicators & Responses to Radicalisation (EU-project; 2009-2013)

- TTSRL: Transnational Terrorism, Security & the Rule of Law (EU-project; 2006-2009)

- The RecoRa report: Recognising and Responding to Radicalisation – Considerations for policy and practice through the eyes of street level workers (.pdf, 2009)

- Ideologie en strategie van het jihadisme (.pdf, 2009, NCTV)

- Radicalisation in Rotterdam III (.pdf, 2008)

- Radicalisation in the Digital Era (2013, RAND)

- Amsterdam against radicalisation (.pdf, 2007)

- Narcis.nl (wetenschappelijke publicaties; zoek naar “radicalisering”, “polarisatie”, “extremisme”, “terrorisme”, etc.)

- FORUM-publicaties (voor wat betreft radicalisering vanuit religieuze hoek)

- AIVD-tekstfragmenten over extremisme

- Boek: Terrorisme (2012, eds. Muller, Rosenthal en De Wijk)

- The Radicals’ City: Urban Environment, Polarisation, Cohesion (.pdf, 2013), door Ralf Brand en Sara Fregonese “[brings] together comparative case studies from Belfast, Beirut, Amsterdam and Berlin, this book examines the role of the urban environment in social polarisation processes.”

- Burgers in veiligheid. Een inventarisatie van burgerparticipatie op het domein van de sociale veiligheid (WODC-onderzoek, 2014)

- The way out: A handbook for understanding and responding to extreme movements (3.2MB .pdf, 2009, Niklas Odén / EXIT Fryshuset)

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police Guide on Radicalization (2015, via Public Intelligence)

- ISIL’s Online Offensive: Challenges in Countering ISIL in Cyberspace (18 juni 2018, door David Fidler, hoogleraar in de rechten aan Indiana University )

- The Virtual ‘Caliphate’: Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda Strategy (.pdf, 2015) h/t @krypt3ia

- Protecting children from radicalisation: the prevent duty (July 2015, UK govt)

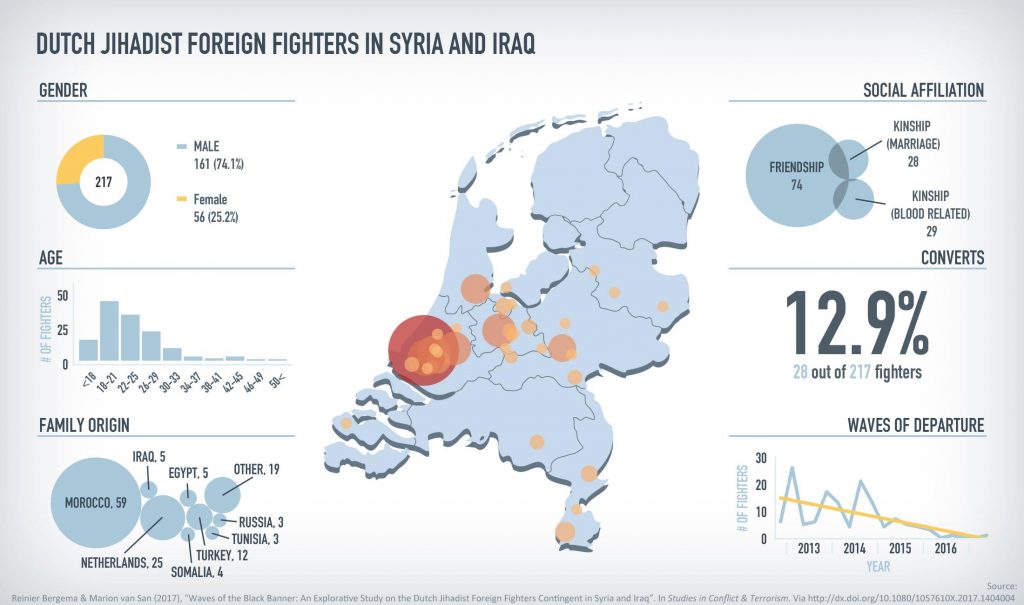

- Nederlandse jihadisten in Syrië en Irak: een analyse (Bergema en Koudijs, Internationale Spectator 10, 2015)

- Sektarische strijd nu ook in Nederland? (Heintzbergen, Van der Heide en Weggemans, Internationale Spectator 10, 2015)

- Risk Assessment Decisions for Violent Political Extremism 2009-02 (Canadese overheid, 2009)

- RadicalisationResearch.org (wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar radicalisering; About)

- Toward a Behavioral Model of “Homegrown” Radicalization Trajectories (Klausen et al. in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Volume 39, Issue 1, 2016; Open Access)

- In Conversation with Morten Storm: A Double Agent’s Journey into the Global Jihad (Bonino, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol 10, No 1, 2016; Open Access)

- Designing and Applying an ‘Extremist Media Index’ (Holbrook, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol 9, No 5, 2015; Open Access)

- Perspectives on Terrorism (tijdschrift, Open Access)

UPDATES (van recent naar oud)

UPDATE 2023-07-31: Cults and Online Violent Extremism (rapport van Global Network on Extremism & Technology / GNET)

UPDATE 2022-04-15: Radicalization in the Ranks: An Assessment of the Scope and Nature of Criminal Extremism in the United States Military

UPDATE 2022-03-25: Journal for Deradicalization, No. 30: Spring 2022 (open access)

UPDATE 2022-03-04: Understanding Youth Radicalisation: An Analysis of Australian Data (Open Access-artikel in Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 2022, v. 14, no. 2)

UPDATE 2019-08-26: Toolkit helpt gemeenten bij tegengaan radicalisering (NCTV). Directe link naar de toolkit: https://www.socialestabiliteit.nl/si-toolkit

UPDATE 2019-08-14: My encounters with CSISRamz Aziz: CSIS arbitrary outreach to Muslim students does everything but identify risk factors for radicalization (opiniestuk van Ramz Aziz o.a. nav contact dat de Canadian Security Intelligence Service aka CSIS met hem zocht)

UPDATE 2019-07-20: A Review of Transatlantic Best Practices for Countering Radicalisation in Prisons and Terrorist Recidivism (.pdf, Europol; 15 pagina’s). Abstract: “Counter terrorism practitioners in Europe and North America have long considered radicalisation within prison systems and the release of incarcerated terrorist offenders as major challenges. The problem has worsened during the past half-decade, as the number of extremist offenders in Western prison systems has metastasised, and previously incarcerated extremists were responsible for attacks that rank amongst Europe’s deadliest. Significant barriers remain to developing effective radicalisation prevention and disengagement programmes in prisons, jails and parole systems, as well as inculcating prison authorities within the counter terrorism infrastructure. Nonetheless, some innovative programmatic responses, albeit on a small scale, are currently in effect. This paper reviews efforts in the European Union and the United States of America to combat extremism in prison and parole systems, highlighting the guidelines, methods and practices which have proven effective or ineffective in certain circumstances.”

UPDATE 2019-07-08: White Supremacist Online Incitement: White Supremacist Neo-Nazi Group Works To Recruit New Members On Gab, Twitter, Instagram, And BitChute – With Intent To Take Violent Action (MEMRI, Special Dispatch No.816. Wikipedia-entry over MEMRI: hier)

UPDATE 2019-06-25: Getting off: The Implications of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Issues Among Former ISIS Fighters for Counterterrorism and Deradicalization. Artikel van dr. Daniel Koehler & dr. Peter Popella, vandaag verschenen bij Small Wars Journal.

UPDATE 2019-06-07: Encrypted Extremism: Inside the English-Speaking Islamic State Ecosystem on Telegram (.pdf, 62 pagina’s; mirror) — nieuw rapport van George Washington University. Begeleidend schrijven/persbericht: Report Details How Islamic State Supporters Use Telegram.

UPDATE 2019-04-03: A Public-Health Approach to Countering Violent Extremism (Michael Garcia, at Just Security)

UPDATE 2019-03-26: Politicoloog Bassam Tibi: ‘Het gaat om het verschil tussen een moslim en een islamist’ (Volkskrant). Introductie: “Achter de rel rond het salafistische Cornelius Haga Lyceum gaat een fundamentele strijd schuil onder moslims in Europa, waarschuwt islamgeleerde Bassam Tibi. ‘Als Europa zijn eigen verlichte moslims niet steunt, geeft het ruimte aan islamistische ondermijning.’ […]”. Over de kwestie rondom Cornelius Haga, zie ook: AIVD: Omstreden shariageleerde op Cornelius Haga Lyceum voor heimelijke bijeenkomsten (AT5) en/of de bron daarvan: AIVD: Britse prediker heimelijk op Haga (NRC Handelsblad; NRC heeft het vertrouwelijke ambtsbericht aan de burgemeester van Amsterdam ingezien).

UPDATE 2019-03-xx: Psychopathologie en terrorisme – Stand van zaken, lacunes en prioriteiten voor toekomstig onderzoek (WODC-onderzoeksrapport). De (volledige) conclusie: “Prevalentiestudies naar psychopathologie bij terrorisme laten zien dat er geen enkelvoudig specifiek profiel is voor terroristen. Psychopathologie lijkt een beperkte rol te spelen bij lone actors en niet specifiek bij groepsterrorisme. Psychische stoornissen zijn bovendien in het algemeen ook niet bruikbaar om statistisch te voorspellen wie wel of niet een terroristische daad zal plegen. Voor iedere stoornis, zelfs als deze relatief vaker bij lone actor terroristen is geconstateerd, geldt dat de overgrote meerderheid van de personen die eraan lijdt, zich nooit aangetrokken zal voelen tot radicalisering of terroristische activiteiten.Toekomstig onderzoek zal nader moeten duiden welke psychische stoornissen vaker voorkomen bij bepaalde specifieke types terrorisme, en met welke geweldsondersteunende factoren deze stoornissen kunnen samenhangen. Kwalitatieve kennis over (behandel)protocollen zal verder op internationaal niveau klinische experts en professionals kunnen assisteren bij gedegen case-management.”

UPDATE 2019-01-23: Veelgestelde vragen radicalisering en polarisatie (Rijksoverheid / JEP).

UPDATE 2019-01-18: Lancering e-magazine Platform JEP: Aandachtsfunctionarissen radicalisering in het jeugddomein (Rijksoverheid / JEP). Directe link: JEPzine 01. (NB: “Platform JEP” = Platform Jeugd preventie Extremisme en Polarisatie)

UPDATE 2018-12-06: Vlaamse aanpak deradicalisering werkt contraproductief: “Vroeger waren we Belgen, nu zijn we moslims” (HLN.be). Inleiding: “Het Vlaamse deradicaliseringsbeleid heeft contraproductieve effecten op kwetsbare jongeren in het jeugdwelzijnswerk. Dat stelt een onderzoek aan de Arteveldehogeschool. Zo worden radicale opinies bij jongeren te vaak geproblematiseerd, terwijl ze horen bij een normale ontwikkeling in de puberteit. De islam wordt dan weer al te vaak gezien als een “gevaarlijk” geloof, wat bij moslimjongeren het gevoel versterkt dat ze tweederangsburgers zijn. ”

UPDATE 2018-10-15: Three reasons why it is difficult to recognize signs of radicalization (post van Marieke van der Zwan op het Leiden Safety and Security Blog; over de recent verijdelde plannen voor een aanslag in Nederland)

UPDATE 2018-09-28: OM: grote aanslag in Nederland verijdeld, verdachten wilden kalasjnikovs en bomvesten gebruiken (Volkskrant). Meer: hier & hier.

UPDATE 2018-07-14: Wanneer is het beleid tegen radicalisering een succes? (artikel in Trouw, door Niels Markus en Kristel van Teeffelen)

UPDATE 2018-06-26: Vroegsignalering van extremisme? De lokale veiligheidsprofessional over risico’s en duiding bij jongeren (.pdf) — rapport van Annemarie van de Weert & Quirine Eijkman (werkzaam bij de Hogeschool Utrecht) over hoe in de Nederlandse Countering Violent Extremism (CVE)-praktijk wordt omgegaan met signalen van (vermeende) radicalisering. Thans zou te veel afhankelijk zijn van onderbuikgevoelens bij lokale veiligheidsprofessionals, wat ongewenste gevolgen kan hebben voor — op de eerste plaats — jongeren. Er wordt aanbevolen om te werken aan bewustzijn onder professionals over normale processen bij identiteitsvorming (waarin ook extreme maar niet-gewelddadige posities normaal kunnen zijn) etc. en aan specifiekere definities van radicalisering en van de doelen die met de CVE-inspanningen worden beoogd. (P.S.: de ‘Handreiking radicalisering en polarisatie’ v/d NCTV in 2012 benoemt het begrip “niet-pluis-gevoel” in de instructie voorafgaand aan de lijst van signalen. Ter opfrissing; “Ook als er geen sprake is van (dreigende) radicalisering kan een ‘niet-pluis-gevoel’ en een aantal signalen duiden op een zorgelijke situatie waarin iets moet gebeuren – ook als het niets met radicalisering te maken heeft.”)

UPDATE 2018-01-29: Haagse ronselorganisatie in hoger beroep voor de rechter (Openbaar Ministerie. Ook beschikbaar in Engels: Dutch terrorist recruitment organisation appears before the Court of Appeal)

UPDATE 2017-12-23: Countering Terrorist Narratives — rapport dd november 2017 door LIBE-commissie v/h Europese Parlement.

UPDATE 2017-12-14: Jihadist Dehumanisation Scale: an interesting way to assess radicalisation (gepost door onderzoekers van de University of Nantes, France)

UPDATE 2017-11-20: NCTV: Dreigingsbeeld Terrorisme Nederland 46 + Rijksoverheid-nieuwsbericht Blijvende dreiging van uitgereisde en lokale jihadisten.

UPDATE 2017-11-17: AIVD-publicatie ‘Jihadistische vrouwen, een niet te onderschatten dreiging’ + AIVD-nieuwsbericht Vrouwen factor van betekenis binnen jihadisme.

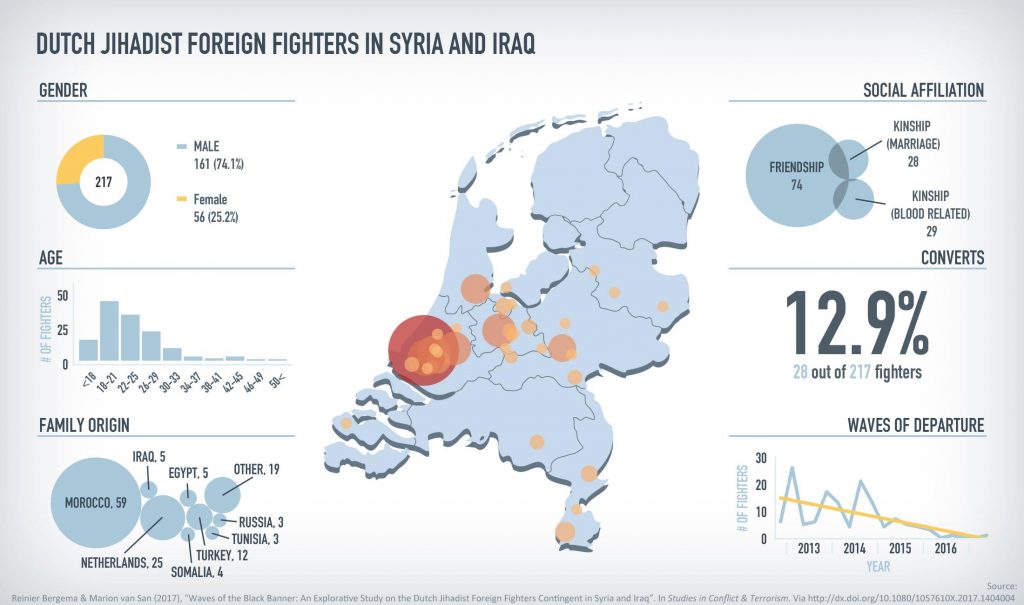

UPDATE 2017-11-13: Waves of the Black Banner: An Exploratory Study on the Dutch Jihadist Foreign Fighter Contingent in Syria and Iraq (wetenschappelijk artikel van Reinier Bergema en Marion van San, gepubliceerd in Journal of Studies in Conflict & Terrorism). Infographic:

UPDATE 2017-11-07: de conceptversie van de “Regeling OCW uitgereisde personen” is in consultatie gebracht. Toelichting bij de consultatie (citaat van website): “De Wet beëindiging uitkeringen, studiefinanciering en tegemoetkoming bij deelname aan terroristische organisatie voorziet in een beëindigingsgrond in de WSF 2000, de WTOS, en de WSF BES voor personen die worden aangemerkt als uitreizigers. In de regeling wordt de wijze waarop de gegevensuitwisseling tussen DUO en de bevoegde veiligheids- en opsporingsdiensten en (I)SZW over uitgereisde personen naar terroristische gebieden plaatsvindt, geregeld”.

UPDATE 2017-11-06: Deradicalizing, Rehabilitating, and Reintegrating Violent Extremists (U.S. Institute of Peace / USIP)

UPDATE 2017-11-02: ‘Betrek militair bij opsporing jihadgangers’ (opiniestuk Bibi van Ginkel, in Trouw)

UPDATE 2017-10-18: Crime as Jihad: Developments in the Crime-Terror Nexus in Europe (Rajan Basra and Peter R. Neumann) + CTC Sentinel Vol 10 Issue 9 (.pdf, oktober 2017, 37p). Abstract: “Throughout Europe, criminal and extremist milieus are merging, with many jihadis and ‘foreign fighters’ having criminal pasts. An individual’s criminality can affect his process of radicalization and how he operates once radicalized. The Islamic State’s recent propaganda suggests that the group is aware of this reality. It has positively framed the crime-terror nexus by encouraging crime ‘as a form of worship,’ and has been lauding those from criminal backgrounds. This has been reflected on the streets of Europe, where perpetrators have used their criminal ‘skills’ to make them more effective terrorists. While understanding of the crime-terror nexus has developed, there are many knowledge gaps that have practical implications for countering terrorism”. Dit issue van CTC Sentinel bevat ook een artikel over gebruik van internet voor ondersteuning van terrorisme: “The Cybercoaching of Terrorists: Cause for Alarm?” (John Mueller).

UPDATE 2017-09-26: Improving Understanding of the Roots and Trajectories of Violent Extremism: Proceedings of a Workshop–in Brief (verslag v/e workshop in Parijs op 20-21 juni 2017, 8 pagina’s; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. .

UPDATE 2017-08-14: IS comes from modern reality, not seventh-century theology (door Jad Bouharoun, column in Middle East Eye)

UPDATE 2017-08-04: Trump Signals Cuts to Unpopular “Countering Extremism” Programs, But Worse Could Be Coming (The Intercept)

UPDATE 2017-07-19: Salafi Jihadism – An Ideological Misnomer (door Sajid Farid Shapoo, in Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2017-07-09: Marketing to Extremists: Waging War in Cyberspace (door Andrew Byers en Tara Mooney, in Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2017-07-04: Philippines’ biggest Muslim rebel group, supports ‘fatwa’ against violent radicalism (Straits Times; op 8 juli 2017 ook op de newsticker van al Jazeera).

UPDATE 2017-07-04: EU LIBE concept-opinie met aanmoediging voor “programmes targeting ‘home-grown terrorists’ and de-radicalisation programmes”: Draft report – EU Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation (Eurojust) – PE 606.167v02-00 – Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (.pdf, dd 4 juli 2017)

UPDATE 2017-07-xx: Europe’s ‘new’ jihad: Homegrown, leaderless, virtual (.pdf, 7 pagina’s; door Thomas Renard, gepubliceerd in Security Policy Brief 89 van Egmont Institute)

UPDATE 2017-06-29: Counter-terrorism was never meant to be Silicon Valley’s job. Is that why it’s failing? (The Guardian) Subtitle: “Extremist content is spreading online and law enforcement can’t keep up. The result is a private workforce that’s secretive, inaccurate and unaccountable”.

UPDATE 2017-06-27: Drie jihadisten bij verstek veroordeeld tot zes jaar (NOS)

UPDATE 2017-06-27: Differential Association Explaining Jihadi Radicalization in Spain: A Quantitative Study (Reinares et al., Combating Terrorism Center / West Point)

UPDATE 2017-05-26: Exploring the Role of Instructional Material in AQAP’s Inspire and ISIS’ Rumiyah (dr. Alastair Reed & dr. Haroro J. Ingram, ICCT; gepresenteerd tijdens de 1st European Counter Terrorism Centre (ECTC) conferentie over online terrorist propaganda, 10-11 april 2017, Europol HQ, Den Haag)

UPDATE 2017-06-16: Countering ISIL’s Digital Caliphate: An Alternative Model (door Bradford Burris, op Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2017-06-15: The Roots of Violent Extremism (door Troy E. Mitchell, op Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2017-06-09: Deconstruction of Identity Concepts in Islamic State Propaganda (.pdf, J.M. Berger, ICCT / Europol)

UPDATE 2017-05-28: tweeluik van Andreas Kouwenhoven in NRC Handelsblad: Overheden maken nieuwe afspraken over privacy potentiële radicalen en Op een ‘watchlist’ – ook als je niets misdaan hebt

UPDATE 2017-05-17: Jihad Joris: Dutch Converts Waging Jihad in Syria and Iraq (door Reinier Bergema, op Bellingcat)

UPDATE 2017-05-11: Belgian fighters in Syria and Iraq – A Closer Look at the Converts (door Guy Van Vlierden en Pieter Van Ostaeyen, op Bellingcat)

UPDATE 2017-05-01: nieuw boek: Nederlandse jihadisten – van naiëve idealisten tot geharde terroristen (door Edwin Bakker en Peter Grol; betreft acht casusbeschrijvingen van jongeren die een radicaliseringsproces doormaakten)

UPDATE 2017-04-25: Lessons Learned from Countering Violent Extremism Development Interventions (door Steph Schmitt, in Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2017-04-18: A Psycho-Emotional Human Security Analytical Framework: Origin and Epidemiology of Violent Extremism and Radicalization of Refugees (door Patrick J. Christian et al., in Small Wars Journal).

UPDATE 2017-03-22: Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories (door Randy Borum, in Journal of Strategic Security Volume 4, No. 4, Winter 2011: Perspectives on Radicalization and Involvement in Terrorism)

UPDATE 2016-10-04: Analyse der Radikalisierungshintergründe und -verläufe der Personen, die aus islamistischer Motivation aus Deutschland in Richtung Syrien oder Irak ausgereist sind (.pdf, 2016, 61 blz; door Bundeskriminalamt, Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz en Hessisches Informations- und Kompetenzzentrum gegen Extremismus)

UPDATE 2016-10-02: Joint Staff Strategic Assessment: Counter-Da’esh Influence Operations Cognitive Space Narrative Simulation Insights (document van de Amerikaanse Joint Staff J39 uit mei 2016 inzake PSYOPS/INFOOPS; beschikbaar gesteld via Public Intelligence)

UPDATE 2016-08-23: Veroordeling voor via social media verspreiden van bestanden waarin tot een terroristisch misdrijf wordt opgeruid (Crime & Tech): voorwaardelijke gevangenisstraf van 6 maanden, met een proeftijd van twee jaren. Volledige uitspraak hier.

UPATE 2016-08-22: Why Europe Can’t Find The Jihadis In Its Midst (door Mitch Prothero, Michael Hastings Fellow). Via /r/intelligence.

UPDATE 2016-08-16: Countering the Narrative: Understanding Terrorist’s Influence and Tactics, Analyzing Opportunities for Intervention, and Delegitimizing the Attraction to Extremism (Jordan Isham en Lorand Bodo, in Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2016-07-11: Kamerbrief voortgang Actieprogramma Integrale Aanpak Jihadisme (Rijksoverheid.nl) van Minister van der Steur (VenJ) en minister Asscher (SZW)

UPDATE 2016-06-14: EU proposes new steps against radicalisation (EU Observer). Citaat: “(…) The EU executive presented on Tuesday (14 June) a communication with propositions (.pdf) to extend current programmes in education, social inclusion, counter-propaganda, cooperation with third countries or addressing radicalisation in prisons. (…)”

UPDATE 2016-06-08: Nederlandse banken krijgen lijst met namen van vermoedelijke jihadisten (Nu.nl). Citaat: “De vier grootste banken van Nederland krijgen van de Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), een overheidsinstantie, een lijst met namen van vermoedelijke jihadisten. De banken kunnen die personen dan controleren op ongebruikelijke transancties. (…)”

UPDATE 2016-06-01: Meer gemeenten ontvangen versterkingsgelden voor de aanpak van radicalisering (NCTV) –> MinV&J trekt in totaal € 2.2 miljoen uit voor de gemeenten Almere (€ 197.320), Amersfoort (€ 117.190), Culemborg (€ 9.100), Gouda (€ 335.000), Haarlemmermeer (€ 131.200), Hilversum (€ 39.455), Leiden (€ 36.275), Maastricht (€ 646.552), Nijmegen (€ 120.000), Nuenen (€ 285.675), Schiedam (€ 168.345) en Zwolle (€ 161.070). In 2015 trok MinV&J € 4,4 miljoen uit voor de gemeenten Den Haag, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Rotterdam, Delft, Arnhem, Zoetermeer en Huizen.

UPDATE 2016-05-07: Wijkagent als geheim wapen tegen radicalisering (NOS)

UPDATE 2016-05-xx: Psychologische Erklärungsansätze zum brutalen Vorgehen der Jihadisten in Syrien und im Irak (BfV, Duits)

UPDATE 2016-04-26: Niet elke salafist is een jihadist; Over salafistische contranarratieven (.pdf, dr. Ineke Roex / UvA, in Magazine nationale veiligheid en crisisbeheersing 2016 – 2)

UPDATE 2016-03-16: Complex dreigingsbeeld reden tot onverminderd grote zorg (NCTV) + Samenvatting Dreigingsbeeld Terrorisme Nederland 41 + TK-brief beleidsimplicaties

UPDATE 2016-02-21: FBI Preventing Violent Extremism in Schools Guide (Public Intelligence; FBI-document van januari 2016)

UPDATE 2016-02-11: Lawsuit Demands Information on Shadowy “Countering Violent Extremism” Programs in U.S. (Murtaza Hussain in The Intercept inzake $69M budget voor CVE-programma’s bij DHS en DOJ)

UPDATE 2016-02-11: Verslag van een algemeen overleg, gehouden op 10 december 2015, over Preventie radicalisering (Tweede Kamer)

UPDATE 2016-01-31: U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory White Paper on Countering Violent Extremism (Public Intelligence,, betreft een in juli 2015 geüpdatete versie van een USAF-rapport uit 2011; 202 pagina’s)

UPDATE 2016-01-29: citaat uit Magazine Nationale Veiligheid en Crisisbeheersing Nr.1 2016 (p.40): “Er komt op korte termijn een digitaal platform www.risicovolleeenlingen.nl om ervaringen en succesvolle oplossingen rondom de problematiek van risicovolle eenlingen te delen”.

UPDATE 2016-01-25: Changes in modus operandi of Islamic State terrorist attacks (.pdf, Europol; mirror; key findings)

UPDATE 2016-01-24: The Country Club Jihad: A Study of North American Radicalization (Alex Reese, in Small Wars Journal)

UPDATE 2016-01-22: Nationaal Actieprogramma tegen discriminatie (Minister van BZK aan Tweede Kamer; incl. vier bijlagen)

UPDATE 2016-01-xx: Spreekverbod zeven imams in Eindhoven tegen radicalisering (Kees-Jan Dellebeke’s blog)

UPDATE 2015-12-09: Eric Schmidt Proposes ‘Hate Spell-Checker’ For Radical and Terrorist Content (Slashdot)

UPDATE 2015-12-08: Minister van der Steur vindt verplichte deradicalisering geen goed idee, zo blijkt uit deze regeringsbrief: Verplichte deradicalisering en administratieve detentie (incl. overzicht van de bevoegdheden). En: Gemeenten akkoord met delen gegevens radicale inwoners (met zinsnede “Het reglement moet voorkomen dat er bij een acuut geval eerst overlegd moet worden of delen van gegevens wel rechtmatig is”; h/t PrivacyNieuws).

UPDATE 2015-12-03: To Thwart Radicalisation, France Is Tightening Security (i-HLS; Frankrijk trekt clearance in van 57 v/d 86,000 cleared medewerkers van de Charles de Gaulle-luchthaven in Parijs vanwege verdenkingen van ‘Islamist radicalism’)

UPDATE 2015-11-24: Besluit Wob-verzoek over toolbox extremisme (uitkomst van Wob-verzoek dat aan NCTV is gestuurd; 750+ pagina’s/slides vrijgegeven)

UPDATE 2015-11-18: EU Parliament to vote on contentious anti-radicalisation Resolution (door Maryant Fernández Pérez, in EDRi-gram)

UPDATE 2015-11-17: NOS besteedt aandacht aan de hulplijn radicalisering (Twitter: @HulplijnRadical) van het Samenwerkingsverband van Marokkaanse Nederlanders (Twitter: @StichtingSMN).

UPDATE 2015-11-16: Samenwerkingsverband Marokkaanse Nederlanders: Maak vuist tegen jihadisme (RTV Utrecht)

UPDATE 2015-11-14: sinds augustus 2015 is het Rijksopleidingsinstituut tegengaan Radicalisering (ROR) operationeel, een- samenwerking tussen NCTV het het opleidingsinstituut van de Dienst Justitiële Inrichtingen (DJI).

UPDATE 2015-11-04: Inside the jihadi lifestyle magazine wars (Madison Pauly, in Hopes&Fears)

UPDATE 2015-10-19: Rachida Dati on the radicalisation of EU citizens: “A truly European response is needed” (Europees Parlement)

UPDATE 2015-10-12: Aanbieding onderzoeken quickscan gemeenten en triggerfactoren radicalisering (Tweede Kamer)

UPDATE 2015-10-10: citaten uit antwoorden op kamervragen aan de Staatssecretarissen van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport en van Veiligheid en Justitie over het bericht dat jeugdzorg niet toegerust is op Syriëgangers:

“Tot en met 1 juli 2015 zijn circa 200 Nederlanders met jihadistische intenties uitgereisd naar Syrië of Irak met het doel zich aan te sluiten bij een terroristische organisatie in de strijdgebieden aldaar. Van deze groep zijn er circa 35 naar Nederland teruggekeerd en circa 37 gesneuveld. Dat betekent dat er op dit moment nog circa 130 Nederlanders met jihadistische intenties in Syrië of Irak verblijven. Over individuele gevallen of verdere uitsplitsing doet het kabinet geen mededelingen. In de periode februari 2013 tot 24 juni 2015 zijn bij de Raad voor de Kinderbescherming 49 unieke aan jihadisme gerelateerde kindzaken in onderzoek genomen. Het ging om 32 kinderen in gezinsverband en om 17 individuele minderjarige potentiële vertrekkers.

[…]

Er is op dit moment geen gescheiden opvang voor geradicaliseerde jongeren. Mij zijn geen signalen bekend dat daar binnen de jeugdhulp behoefte aan is. Instellingen voor jeugd- en opvoedhulp bieden een pedagogisch leefklimaat. Bepalende aspecten daarvoor zijn de relatie tussen de groepsopvoeder en de jongere, de opvoeding en verzorging, en de bejegening, de behandeling en sfeer in de groep. Het risico van overdracht van radicale denkbeelden bestaat, maar is beheersbaar. Op dit moment vindt de opvang en behandeling plaats binnen reguliere programma’s en waar nodig betrekken de instellingen kennis en kunde van buiten. De Raad voor de Kinderbescherming, die voor deze jongeren vaak de instantie is die de machtiging aanvraagt, is voortdurend in gesprek met de jeugdhulp om te bezien wat de beste aanpak is voor deze jongeren binnen de jeugdhulp.

[…]

In het Actieprogramma Integrale Aanpak Jihadisme (29 augustus 2014, bijlage bij Kamerstuk 29754, nr. 253) is een faciliteit aangekondigd die trajecten aanbiedt voor geradicaliseerde jongeren die openstaan voor een alternatief om te re-integreren in de samenleving buiten het jihadistische netwerk: “Een nieuw op te richten Exit-faciliteit in Nederland. Personen die uit het jihadisme willen stappen worden onder strenge voorwaarden begeleid door deze exit-faciliteit. Hiermee wordt hen onder andere een (beter) toekomstperspectief geboden. Ondersteuning door middel van psychologische hulpverlenging kan hier onderdeel van zijn.” (Maatregel 13 uit het Actieprogramma).

In de afgelopen maanden is de organisatie van deze faciliteit verder uitgewerkt. Momenteel worden de medewerkers geworven en in september dit jaar zal de faciliteit operationeel zijn.

De trajecten zullen op maat gemaakt zijn en kunnen bestaan uit – een combinatie van – individuele mentoring (bijvoorbeeld coaching op relatievaardigheden en zelfreflectie), psychologische of psychiatrische support, counseling, groepsbijeenkomsten (bijvoorbeeld ‘anger management’) en praktische ondersteuning van het individu. Deze ‘exit-faciliteit’ gaat zorg dragen voor een geselecteerde pool van experts. De effectiviteit van ingezette trajecten zal worden gemonitord.

In de volgende Voortgangsrapportage (voorzien op 9 november 2015) zal uw Kamer uitgebreider worden geïnformeerd over deze faciliteit en de werkwijze. Daarbij zal ook worden ingegaan op de doelgroepen, de financiering en welke organisaties een beroep kunnen doen op de faciliteit.”

UPDATE 2015-09-30: Rijksopleidingsinstituut Radicalisering: Alle opleidingen over het tegengaan van radicalisering onder één dak (NCTV)

UPDATE 2015-09-24: Radicalisation awareness information kit (Australische overheid, gaat over alle variaties/thema’s van radicalisering; er is enige controverse over verbanden die in de kit zouden worden gelegd tussen groene politiek, alternatieve muziek en terrorisme)

UPDATE 2015-09-24: AIVD: geen signalen voor golf van IS-strijders in Nederland (Volkskrant)

UPDATE 2015-09-23: Invloed salafisme in Nederland toegenomen (NCTV, nieuwsbericht bij publicatie (.pdf) en beleidsreactie (.pdf)). Bijhorend: Salafisme in Nederland: diversiteit en dynamiek (AIVD). Die laatste bevat een vereenvoudigde weergave van het salafistisch landschap:

UPDATE 2015-09-23: EU Parliament’s “radicalisation” draft report – lost in translation (Joe McNamee in EDRi-gram)

UPDATE 2015-08-26: de daders van de aanval op Charlie Hebdo zijn niet online geradicaliseerd, aldus (in Frans) Le Monde. (via)

UPDATE 2015-08-20: gemeente Almere: ‘Informatie bij mogelijke radicalisering makkelijker inzichtelijk’ (h/t PrivacyNieuws.nl)

UPDATE 2015-07-01: EU Observer meldt: “The EU’s police agency Europol on Wednesday launched its web unit tasked to hunt down online extremist propaganda. Europol’s director Rob Wainwright said the unit is “aimed at reducing terrorist and extremist online propaganda.” The unit consists of over a dozen Europol officials and experts from national authorities.”

UPDATE 2015-07-xx: Rethinking countering violent extremism: implementing the role of civil society (Anne Alya, Anne-Marie Balbia en Carmen Jacquesa, in Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism, Volume 10, Issue 1, 2015; Open Access)

UPDATE 2015-06-29: de NCTV heeft de openbare versie van het Dreigingsbeeld Terrorisme Nederland 39 gepubliceerd., samen met een voortgangsrapportage inzake het actieprogramma Integrale Aanpak Jihadisme. In beide is onder meer aandacht voor radicalisering.

UPDATE 2015-06-23: in de hoofdlijnen van het Jaarplan AIVD 2015 wordt radicalisering genoemd (Minister van BZK)

UPDATE 2015-06-18: CBP: Anti-jihad-software op school gaat te ver (BNR Nieuwsradio)

UPDATE 2015-06-07: gepubliceerd onderzoek naar 140 (!) Nederlandse politiedossiers over radicale islamisten, uitgevoerd door de Landelijke Eenheid van de Nederlandse politie in de periode februari en november 2014, laat zien dat de helft van de Syriëgangers waarover een politiedossier bestaat, kampt met psychische problemen; en dat één op de vijf te maken heeft (of heeft gehad) met ernstige gedragsproblemen, of met een vastgestelde stoornis zoals schizofrenie. In geen van de onderzochte gevallen zou sprake zijn van een afgeronde hogere opleiding, en in geen van de gevallen van een ‘stabiele loopbaan’. De uitkomsten van de studie staan haaks op beeldvorming waarin Syriëgangers worden neergezet als in het algemeen normale, gezonde, hoogopgeleide individuen. Waarschijnlijk bestaan er normale, gezonde, hoogopgeleide Syriëgangers die niet in politiedossiers voorkomen en dus buiten het blikveld van deze studie vallen; mogelijk zijn de effecten van die eventuele selection bias verwaarloosbaar. De studie doet uitspraak over afgeronde hogere opleidingen, maar niet over studenten aan hogere opleidingen: in juni 2014 — dus tijdens deze studie — stelde (.pdf) de AIVD dat “sommige jihadisten” een hbo-opleiding doen, of studeren aan een universiteit; en in november 2014 verscheen een mediabericht over een Syriëganger die hbo-student zou zijn.

UPDATE 2015-06-03: Kamerbrief van Minister Bussemaker van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap over aanvullende aanpak onderwijs en radicalisering: de Rijksoverheid afspraken maakt met de 18 gemeenten waar de problematiek van radicalisering het meest speelt. Die afspraken passen bij bestaande activiteiten op lokaal niveau. Gemeenten wordt gevraagd op basis van hun inzicht en kennis onderwijsinstellingen uit het VO en MBO uit te nodigen die voor deze extra ondersteuning in aanmerking zouden komen, en “[het] ondersteuningsaanbod zal hoofdzakelijk bestaan uit trainingen voor schoolbesturen en onderwijsprofessionals. Aanvullend ondersteunend aanbod bestaat uit burgerschaps- en debatactiviteiten voor leerlingen. In het najaar van 2015 start deze complementaire aanpak in twee pilotgemeenten en vanaf januari 2016 volgt deze aanpak in de overige zestien gemeenten.”

UPDATE 2015-05-28: Verslag van het werkbezoek van de Minister Asscher van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid op 24 en 25 maart 2015 aan Marokko inzake gesprekken over onder andere integratie en (de)radicalisering (.pdf).

UPDATE 2015-05-26: 1) Antwoorden van Minister Bussemaker van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap op kamervragen over de kritiek vanuit het onderwijsveld op huidige aanpak op het voorkomen van radicalisering onder jongeren, en 2) antwoorden op kamervragen over het bericht «Kritiek op aanpak radicalisering».

UPDATE 2015-05-23: sancties zijn een obstakel voor deradicaliseren, stellen Beatrice de Graaf en Daan Weggemans in het onderzoeksrapport Na de vrijlating (.pdf, 2015).

UPDATE 2015-05-11: new from EU LIBE Committee: Working document on prevention of radicalisation and recruitment of EU citizens by terrorist organisations (.pdf, rapporteur: Rachida Dati)

UPDATE 2015-04-07: Voortgang Actieprogramma Integrale Aanpak Jihadisme (.pdf, Rijksoverheid).

UPDATE 2015-04-09: Notitie antidemocratische groeperingen (Tweede Kamer, verslag AO + de notitie)

UPDATE 2015-04-xx: Online Radicalization (.pdf, artikel uit het april/juni 2015-nummer van Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin / US Army)

UPDATE 2015-03-16: Antwoorden van de Minister Bussemaker & Stas Dekker van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap op kamervragen over aanpak radicalisering op scholen.

UPDATE 2015-03-04: “Government agencies are using models of radicalization which don’t reflect reality”, zegt dit artikel in The Intercept inzake de gebroeders Tsarnaev van de Boston Marathon Bombing. [Addendum: Boston Bomber Tsarnaev laat zien dat we dogma’s moeten loslaten, door dr. Teun van Dongen.]

UPDATE 2015-02-26: het Magazine Nationale veiligheid en crisisbeheersing, 2015 nr. 1 (.pdf) bevat artikelen over jihadisme en radicalisering.

UPDATE 2015-02-17: Public Intelligence bericht over een rapport (.pdf; mirror) van de US Army Asymmetric Warfare Group getiteld “Psychological and Sociological Concepts of Radicalization” (2010). Dat rapport bevat een heldere en beknopte uiteenzetting van theorieën t.a.v. gedragingen (bijv. relative deprivation, groepsdynamica, psychoanalyse) en mechanismen van radicalisering (massa, groep, individu).

EOF