In het WODC-onderzoeksprogramma 2015 (.pdf) staan 70 onderzoeken gepland. Hierbij een selectie van onderzoeken die binnen m’n eigen interessegebied vallen.

Vanuit het Directoraat Generaal Jeugd en Sanctietoepassing:

25 Haalbaarheidsonderzoek dark number jeugdige cybercriminelen (extern)

In 2013 heeft het WODC een onderzoek uitgevoerd naar de bestaande kennis op het terrein van jeugd en cybercriminaliteit. De conclusie daarvan luidt dat de prevalentie meevalt. Tegelijkertijd wordt geconstateerd dat er nog veel onbekend is. De indruk bestaat dat bepaalde categorieën van jeugdige cybercriminelen mogelijk onderbelicht zijn in de beschikbare gegevens en dat er mogelijk sprake is van een hoog dark number. Dit haalbaarheidsonderzoek moet inzicht geven in methoden voor een goede inschatting van het dark number van cybercrime.

Vanuit het Directoraat Generaal Rechtspleging en Rechtshandhaving en Openbaar Ministerie:

33 Nationale Veiligheidsindex 2015 (intern)

De NVI is een methode om zo betrouwbaar mogelijk de ontwikkeling in criminaliteit, overlast en onveiligheidsbeleving op landelijk niveau te beschrijven. Het doel van de NVI is de veelheid aan bestaande indices te vervangen en te komen tot een politiek-bestuurlijk bruikbare, duidelijk te communiceren rapportage over de ontwikkeling van de sociale veiligheid in Nederland. In oktober 2014 is de eerste NVI verschenen. In 2015 zal een nieuwe NVI worden opgeleverd, die duidelijk moet maken of een uitbreiding met cybercrime mogelijk is.

[…]

37 Inventarisatie opsporingstechnologie (extern)

Opsporingstechnologie ontwikkelt zich snel. Politie en openbaar ministerie zetten bij de opsporing en vervolging van misdrijven diverse technieken in, zoals DNA-onderzoek, analyse van camerabeelden en dactyloscopisch onderzoek. Het scala van opsporingstechnieken is groot en het ontbreekt aan een goed overzicht, zowel van de beschikbaarheid als van het gebruik dat ervan wordt gemaakt. Daarnaast ontbreekt overzicht van technologische ontwikkelingen (innovaties). Inzicht hierin is van belang voor de sturing van opsporing en vervolging.

[…]

49 De huidige stand van zaken met betrekking tot het onderzoek ten behoeve van de waarheidsvinding aan inbeslaggenomen elektronische gegevensdragers en inbeslaggenomen geautomatiseerde werken (extern)

Op dit moment mag een opsporingsambtenaar onderzoek doen aan inbeslaggenomen (elektronische) gegevensdragers en geautomatiseerde werken, zoals smartphones, laptops, computers, tablets, usb-sticks, externe harde schijven etc. Hij behoeft hiervoor geen toestemming of machtiging van de officier van justitie of rechter-commissaris. Ook bevat het wetboek geen regels over notificatie, het bewaren en vernietigen van niet-relevante gegevens, het ontoegankelijk maken van gegevens enzovoort. Deze situatie vertoont een grote mate van onevenwichtigheid ten opzichte van de regeling van de andere bevoegdheden tot het vergaren van vastgelegde gegevens, waarbij in beginsel de officier van justitie beslissingsbevoegd is. Gelet op het nog steeds groeiende gebruik van computers en smartphones waarop steeds grotere hoeveelheden gegevens van verschillende aard kunnen worden opgeslagen en het belang dat wordt gehecht aan bescherming van de persoonlijke levenssfeer in verband met dergelijke opgeslagen gegevens, wordt overwogen dit onderwerp in het Wetboek van Strafvordering nader te normeren. Daarvoor is inzicht in de huidige praktijk gewenst.

Vanuit de Cluster Secretaris Generaal:

52 Procedurele en inhoudelijke criteria voor wetsevaluaties (intern)

Wetten worden periodiek geëvalueerd. Volgens Aanwijzing 164 lijkt een evaluatietermijn van vijf jaar in de rede te liggen. Een evaluatiebepaling in deze Aanwijzing zegt dat – indien wenselijk – een wet éénmalig of periodiek wordt geëvalueerd en verslag wordt gedaan over de doeltreffendheid en de effecten van deze wet in de praktijk. In aanmerking komen zowel de mate van verwezenlijking van de doelstellingen en de neveneffecten als de evenredigheid, subsidiariteit, uitvoerbaarheid, handhaafbaarheid, afstemming op andere regelingen, eenvoud, duidelijkheid en toegankelijkheid. Voor een effectief wetsevaluatiebeleid is van belang dat wetsevaluaties aan bepaalde criteria voldoen. Maar welke zijn dat dan? Er is behoefte aan een handreiking of model om een goede wetsevaluatie op te zetten.

53 Gebruik, waardering en effect van internetconsultatie (extern)

De kwaliteit van het wetgevingsproces wordt verhoogd door burgers, bedrijven en organisaties tijdig te informeren over wetgeving in voorbereiding en hen uit te nodigen daaraan een bijdrage te leveren en zo voorstellen te toetsen aan de praktijk. Ook wordt de kwaliteit van wetgeving versterkt door gevraagde of ongevraagde adviezen van adviesorganen. De vraag is of op dit moment het volle potentieel uit consultaties wordt gehaald. Dit onderzoek moet uitwijzen wat de aard, omvang én het effect zijn van het gebruik van internetconsultatie. Hoe waarderen gebruikers internetconsultatie en wat is er te zeggen over de relatie tussen internetconsultatie en het draagvlak van de regeling in kwestie?

Vanuit de NCTV:

54 Cyber-vitaal (extern)

Het is wenselijk om meer inzicht te krijgen in de vitale processen en diensten in het cyberdomein, in de (onderlinge) afhankelijkheden en in het risico dat deze processen en diensten een doelwit worden van cyberaanvallen. De wijze waarop andere landen omgaan met deze vraagstukken kan hierbij worden betrokken. Het achterliggende doel van deze risicobenadering is het verhogen van de weerbaarheid van vitale processen en diensten en het inzetten op een effectieve gezamenlijke respons: publiekprivaat, civiel-militair en met behulp van internationale partners.

55 Evaluatie Nationale Cybersecurity Research Agenda (extern)

Onder de vlag van de Nationale Cybersecurity Research Agenda (NCSRA) zijn meerdere miljoenen euro’s bijeengebracht om onderzoek te doen op het gebied van cybersecurity. In 2013 is de tweede NCSRA verschenen. In dit onderzoek wordt bekeken wat er tot dusver met deze onderzoeksgelden is gedaan en tot welke resultaten dat heeft geleid.

[…]

57 Wisselwerking en mogelijke confrontaties tussen extreemrechts en jihadisme (extern)

In het Verenigd Koninkrijk en Duitsland zijn al vaker fysieke confrontaties geweest tussen extreemrechtse groeperingen en radicale moslims. Soms is dit zelfs geëscaleerd tot voorgenomen (maar verijdelde) moordaanslagen op de leiders van de respectievelijke groepen. In Nederland hebben we dit soort escalaties tussen extreemrechts en radicale moslims nog niet gezien. Welke factoren en dynamiek hebben in landen als het Verenigd Koninkrijk en Duitsland tot de genoemde confrontaties geleid en in hoeverre zijn onderscheiden factoren ook voor Nederland relevant?

58 Effectiviteit van counter narratives (extern)

In het kader van preventiebeleid worden door de Nederlandse overheid gematigde tegengeluiden tegen extremistische vertogen gestimuleerd met als doel om radicalisering tegen te gaan. Het gaat hier hoofdzakelijk om initiatieven die het gewelddadige jihadistische vertoog scherp tegen het licht houden en deconstrueren. Ook in andere (niet-Westerse) landen worden dergelijke geluiden door de overheid gestimuleerd of zelfs door de overheid geformuleerd. De vraag is welke methode effectief is en bij welke (elementen uit de) buitenlandse aanpak de Nederlandse overheid baat zou hebben.

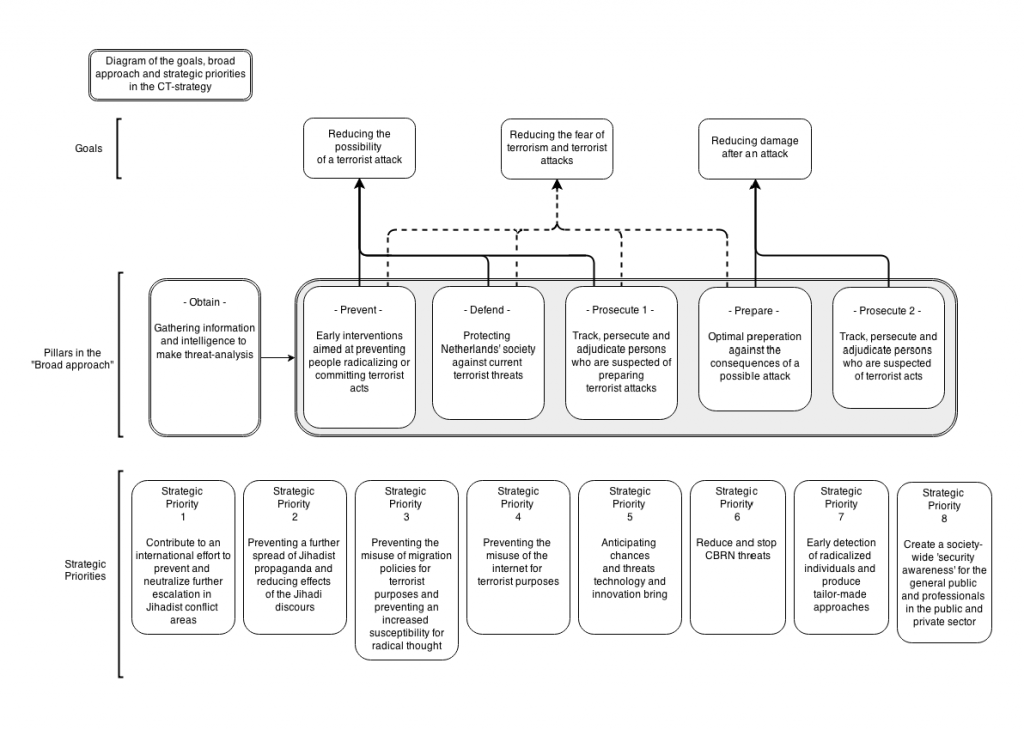

59 Evaluatie Nationale Contraterrorisme Strategie 2011-2015 (extern)

De doelstelling van de Nationale Contraterrorisme Strategie is het verminderen van het risico op een terroristische aanslag en de vrees daarvoor, evenals het beperken van de mogelijke schade na een eventuele aanslag. De strategie wordt periodiek geëvalueerd; de eerstvolgende evaluatie start in 2015. Het onderzoek moet uitwijzen of de strategie op de genoemde terreinen effectief is geweest en daarnaast een overzicht geven van de kosten van de maatregelen voortvloeiend uit de strategie. Hoe verhouden deze kosten zich tot de resultaten?

60 Toegang en invloed van buitenlandse investeerders in de Nederlandse vitale sectoren (extern)

De (mogelijke) overname van, c.q. investering in enkele voormalige Nederlandse nutsbedrijven door buitenlandse partijen heeft het thema van buitenlandse investeringen op de beleidsagenda gezet van de ministeries van EZ en VenJ. De vraag daarbij is hoe nationale veiligheidsbelangen kunnen worden gewaarborgd wanneer voormalige nutsbedrijven in handen komen van staatsbedrijven uit landen waarmee Nederland niet direct dezelfde internationale belangen nastreeft. Meer in het bijzonder spelen daarbij issues als hoe ver de inzage reikt van (toekomstige) buitenlandse aandeelhouders in vertrouwelijke informatie van bedrijven in de Nederlandse vitale sectoren, de toegang tot vertrouwelijke publiek/private samenwerkingsverbanden en de eventuele invloed op cruciale besluitvorming ten aanzien van safety/ cybersecurity. Welke impact kunnen dergelijke aandeelhouders in theorie hebben op de wijze waarop het Nederlandse veiligheidsbestel is ingericht? En zijn er al voorbeelden van daadwerkelijk gebruik door buitenlandse aandeelhouders van mogelijkheden tot toegang, inzage en invloed in Nederland, Europa of daarbuiten?

[…]

EOF