In March 2015, Dutch Freedom of Information (FOI) expert Roger Vleugels (Twitter: @RogerVleugels; LinkedIn: Roger Vleugels) sent a mailing about his upcoming FOI courses. That mailing had attached an English leaflet entitled “The Netherlands: a freedom of information toddler”, that contains reflections by Vleugels on the state of play of FOI in the Netherlands. Here are the contents of that leaflet (published with permission):

The Netherlands: a freedom of information toddler

A country with a FOIA paradox: few requests, lots of obstruction and lots of successQuite contradictory to its image, the level of transparency in the Netherlands is poor. Within the government bodies the urge to improve the transparency is even poorer.

However, especially in the eyes of the Dutch themselves, the image of the Netherlands is one of a transparent country.For sure, we are one of the first countries with a FOIA, a Freedom of information act in power. Worldwide the seventh. The first FOIA, the Wob, came into power in May 1980 after nine years of parliament and cabinet obstructions. This Wob in itself is a quite liberal FOIA.

Almost no use was made of the Wob in the first ten years of its existence. On national level, the use grew from a couple of hundred requests per year in the early nineteen nineties, via 1.000 at the turn of the millennium, to about 2.000-2.500 per year today.

On local level, almost no requests were filed in the last centuries. Serious requesting at a local level started some fifteen years ago and has stabilized at about five or six thousand requests per year, for all the about 400 municipalities combined.Compared to its use in comparable countries, like the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian ones, the use of the Wob is poor. Per capita, the Netherlands file 5 to 10 times fewer requests.

The reason why we file so little requests is the same reason why the Dutch parliament has a poor inquiry performance: We simply have no inherent cultural desire to be or to have govern- ment watchdogs. We tend to believe our ministers and civil servants, with little questions asked. Despite that, one of our export products is transparency.

There are more paradoxes. Using the Wob, verb: wobbing, meets obstruction on an above average level. And, a paradox again, the success rate is also above average.

Obstruction is fierce. Lots of time delay; copious misuse of exemptions; idiotic exemptions like ‘disproportionate disadvantage’; a very broad definition of ‘personal deliberations’; Wob-offices are understaffed and have fairly unskilled civil servants. There are almost no courses for Wob- officials. This obstruction has grown bigger in recent years, largely as a result of a more and more imperious government style.

On the other hand: The few Dutch requesters that do attempt to free information using the Wob, are fairly high skilled, and generally very persistent. They file relatively many complaints and court appeals, on average resulting in over than ten major disclosures each month. Month after month, year after year.

In 35% of the cases, the first decision after filing a Wob request results in a satisfactory level of disclosure. This figure rises to 45% after an administrative complaint, to 65% after a court appeal, and to 75% after a high court appeal.

Since 1986 I filed for or with my clients 5,000 requests, 2,500 administrative complaints, 800 court appeals and 100 high court appeals. Most of my clients are mainstream Dutch press organizations. Among my clients are also special interest groups, NGO’s, researchers and private persons.

In this leaflet you find a selection of the successful ones, to give you an impression of the topic range. Not included are, of course, operational cases.

Regards, Roger

Vleugels publishes two free-of-charge monthly journals, funded by himself and voluntary donations from subscribers (suggested donation: EUR 42 per year):

- Fring Intelligence: “Fringe Intelligence offers a selection of dozens of articles on not yet established intel news or on intel news next to mainstream. There are special sections on Natural resources intelligence and on Intelligence 2.0.”

- Fringe Spitting: “Fringe Spitting provides news and tools for FOIA and Wob specialists with a focus on litigation.”

The journals “have 3,000+ subscribers in 115 countries: 55% intelligence specialists, 30% press, 15% FOIA/Wob specialists”. To receive samples, send a mail with subject “FRINGE SAMPLES” to . To subscribe, send one with subject “START FRINGE”.

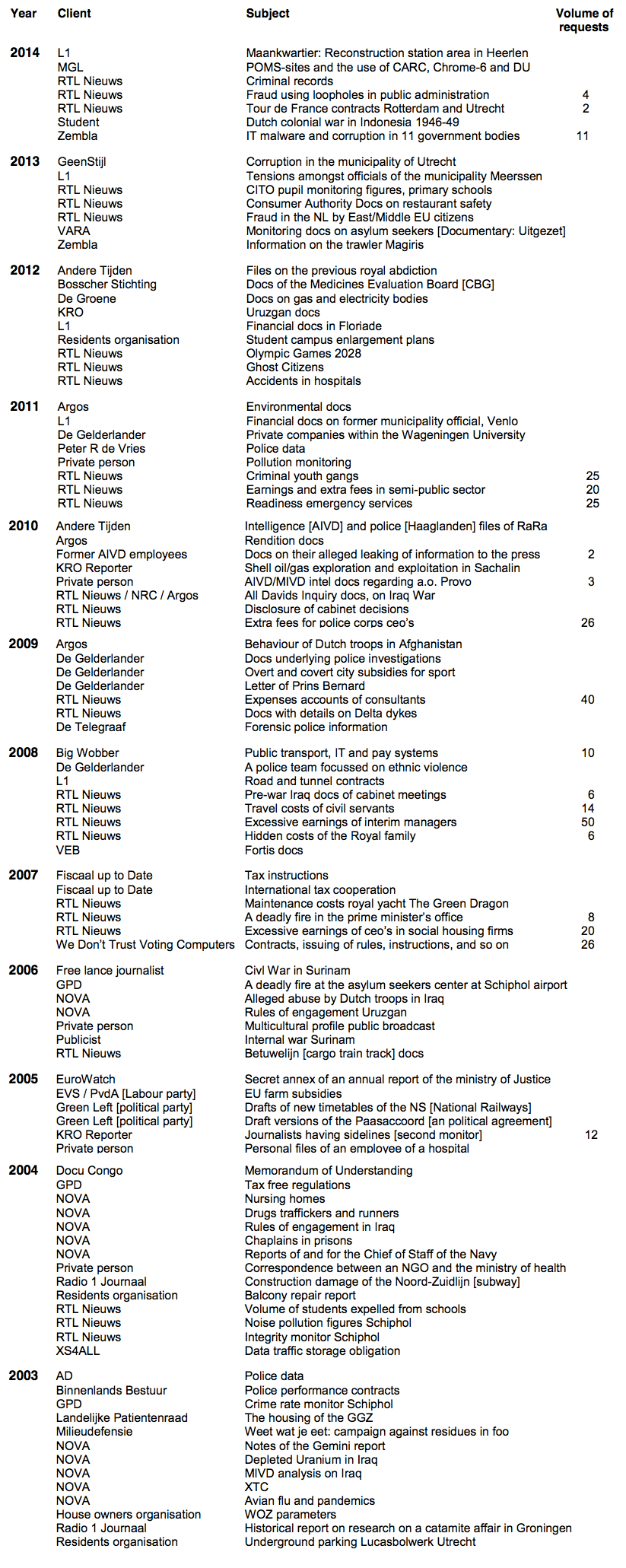

Vleugels’ provides the following overview of his activities between 2003 and 2014 (note: he lectures on FOI since 1986):

Related:

- 2014-08-21: [Dutch] Roger Vleugels’ reactie op de internetconsultatie Wet voorkomen misbruik Wob

- 2014-08-16: [Dutch] Mijn reactie op de internetconsultatie Wet voorkomen misbruik Wob

2014-02-23: [Dutch] Roger Vleugels: Wobben in 10 minuten

EOF