UPDATE 2014-03-11: today, a new CTIVD oversight report was published, together with the Dutch cabinet’s response to the Dessens report. The report covers exercises of various telecom-related powers by the AIVD and MIVD. Concerning the undirected (bulk) collection of phone metadata from wireless sources, the CTIVD has now established that it has not been motivated as required by law: nothing is known about necessity, proportionality or subsidiarity of such collection. IMHO the new report — which only exists as a result of Snowden’s revelations — reemphasizes that up until today, oversight on Dutch SIGINT is broken.

UPDATE 2014-02-10: here (.pdf, in Dutch) are the answers from the Minister of the Interior and the Minister of Defense to the Parliamentary Questions concerning the metadata and the incorrect information supplied by the Minister of the Interior in October/November 2013. These will be debated in Parliament tomorrow.

UPDATE 2014-02-09b: post updated with citations from CTIVD report Nr. 28 and information about Article 26 WIV2002. If you see errors in my post, please report them to koot at cyberwar dot nl.

UPDATE 2014-02-09: also see this excellent post by Peter Koop (@electrospaces).

As reported on Dutchnews it was the Netherlands, not the U.S., who gathered info from 1.8 million phone calls. It concerns foreign intelligence, collected in the context of counter-terrorism and military operations abroad (e.g. Afghanistan). The legal powers exercised by (likely) the Dutch military intelligence & security agency MIVD in collecting the metadata involve Article 26 (SIGINT ‘search’) and Article 27 (SIGINT ‘selection’) of the Dutch Intelligence & Security Act of 2002 (WIV2002).

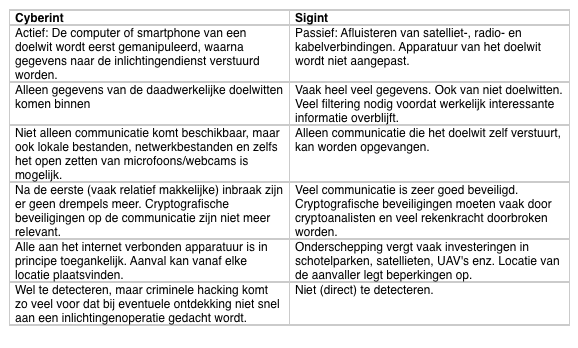

The MIVD published slides (.pdf, in Dutch), dated December 18th 2013, on the topic of interception, metadata and the WIV2002. Slide 5 lists Article 24-27 from the WIV2002 (italic parts are mine):

- Art. 24: directed penetration of automated work (requires permission from head of service or Minister)

- This is the power the AIVD exercises to hack jihadist internet fora.

- Art. 25: directed interception from the cablebound and non-cablebound (requires permission from Minister)

- E.g. directional microphone, telephone tap (landline, GSM), data tap (IP, email).

- One smartphone can technically involve two taps: one for voice, one for data.

- E.g. directional microphone, telephone tap (landline, GSM), data tap (IP, email).

- Art. 26: exploration of interception from the ether (=’SIGINT search’)

- source or destination must be foreign (i.e., domestic communication cannot be explored)

- exploring and determining whether data is relevant to the agency’s statutory duties

- Art. 27-1: undirected interception from the ether

- interception itself is undirected

- to see what to target, for instance through metadata analysis or encryption detection

- Art. 27-3 (=’SIGINT selection’)

- selecting and inspecting content (requires permission from Minister)

- 27-3-a: selection by identity (name of person or organization)

- 27-3-b: selection by technical characteristic (some identifying number, e.g. phone number or IP address)

- 27-3-c: selection by keywords. Minister annually approves list of topics -> AIVD/MIVD determine the exact keywords per topic.

The oversight carried out by the Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services (CTIVD) on lawfulness of exercise of the Article 27-3 power by the general intelligence & security service AIVD is structurally broken: this is evident from CTIVD oversight reports 19, 26, 31 and 35 that cover 2008 to 2013. A single-page extract of the relevant paragraphs is available here (.pdf, in Dutch). Key problem: the oversight is based on analysis of motivation expressed in permission requests that the AIVD sends to the Minister of the Interior to get permission for exercising the Article 27-3 powers, and those requests keep lacking proper motivation.

Concerning the MIVD, CTIVD oversight report 28 (.pdf, in Dutch, 2011) describes problems in (among others) the exercise of Article 26 and Article 27 between 2007 and 2010. For oversight on the exercise of the Article 27 selection powers by the MIVD the same problem exists as for the AIVD: requests for permission (sent to the Minister of Defense in case of the MIVD) are insufficiently motivated, withholding the CTIVD from making a statement about legality. The Article 26 searching power is intended to identify the radio/satellite channels to include in bulk data collection. The report states the following concerning the exercise of Article 26 by the MIVD:

“The CTIVD notes that the reason for and purpose of conducting a SIGINT search focused on SIGINT selection can vary. At least the following common practices can be distinguished:

- The searching of the bulk of communication to determine whether it is possible to generate the desired data using the selection criteria for which permission has been granted;

- The searching of the bulk of communication to identify targets;

- The searching of the bulk of communication for data from which, in the context of an expected new area of investigation, future selection criteria can be derived. “

Original Dutch: “De Commissie constateert dat de aanleiding voor en het doel van het uitvoeren van een searchactiviteit gericht op selectie gelegen kunnen zijn in meerdere zaken. Zij onderscheidt in ieder geval de volgende gangbare praktijken:

1. Het searchen van de bulk aan communicatie om te bepalen of met de selectiecriteria waarvoor toestemming is verkregen de gewenste informatie kan worden gegenereerd

2. Het searchen van de bulk aan communicatie om potentiële ‘targets’ te identificeren of te duiden;

3. Het searchen van de bulk aan communicatie naar gegevens waaruit, in het kader van een verwacht nieuw onderzoeksgebied, toekomstige selectiecriteria kunnen worden afgeleid.”

The CTIVD stated that (1) is permissible and that (2) and (3) are not permissible (hence: unlawful); and that all three variations were observed in daily practice at the MIVD.

None of the above means that the bulk metadata collection by the NSO or the sharing of the data with the NSA is unlawful. It does mean that the Dutch Parliament should pay real close attention to the matter of oversight on the exercise of special powers, notably Article 24-27, in the upcoming debate on the renewal of the WIV2002. That debate will likely result in expansion of the legal power of undirected interception to cablebound communications, enabling the Dutch services to carry out TEMPORA-like programs. To my knowledge, the CTIVD has never investigated the lawfulness of the exercise of the hacking power provided by Article 24 WIV2002 — the article cited by the AIVD as being the power exercised to hack jihadist internet fora. The Dutch Parliament should also specifically pay attention to oversight on Article 24 WIV2002, considering that no public oversight information exists concerning the exercise of this power over the last decade.

The remainder of this post provides details and background on last week’s revelation that it was not the Americans, but the Dutch who collected the 1.8M telephony metadata records.

On February 4th 2014, a short letter (.pdf, in Dutch) was sent to the Dutch parliament by the minister of Defense (responsible for military intelligence & security agency MIVD) and the minister Interior (responsible for general intelligence & security agency AIVD). My translation of the letter:

On August 5th, the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel published a graph that would originate from one of the documents brought out by Snowden. The data available at that time made it likely that the number of 1.8 million would point to metadata of telephone traffic between the United States and The Netherlands. [Note: that graph published by Der Spiegel originates from BOUNDLESS INFORMANT. It shows “Netherlands – last 30 days” and the number “1.831.506”. The minister of the Interior claimed on Dutch television (October 30th 2013) and in Parliament (November 6th 2013) that it was not the Netherlands, but the U.S. who collected this data, and hence that such data had not shared by the AIVD with the NSA. He warned the U.S. that spying on allies is `unacceptable’. (Although in intelligence circles it is a widely known and accepted fact that friends do spy on friends to a certain extent.)]

Original Dutch: “Op 5 augustus jl. heeft het Duitse weekblad Der Spiegel een grafiek gepubliceerd die afkomstig zou zijn uit één van de documenten die door Snowden naar buiten zijn gebracht. De toen beschikbare gegevens maakten het aannemelijk dat het getal van 1,8 miljoen zou wijzen op metadata van telefoonverkeer tussen de Verenigde Staten en Nederland.”

However, additional information and according to further research and analysis of the published data have led to the following conclusion. The graph in question points out circa 1.8 million records of metadata that have been collected by the National Sigint Organization (NSO) in the context of counter-terrorism and military operations abroad. It is therefore expressly data collected in the context of statutory duties. The data are legitimately shared with the United States in the light of international cooperation on the issues mentioned above.

Original Dutch: “Aanvullende informatie en vervolgens nader onderzoek en analyse van de gepubliceerde gegevens hebben echter geleid tot de volgende conclusie. De bedoelde grafiek wijst op circa 1,8 miljoen records metadata die door de Nationale Sigint Organisatie (NSO) zijn verzameld in het kader van terrorismebestrijding en militaire operaties in het buitenland. Het betreft dus uitdrukkelijk data verzameld in het kader van de wettelijke taakuitoefening. De gegevens zijn rechtmatig gedeeld met de Verenigde Staten in het licht van internationale samenwerking op de hierboven genoemde onderwerpen.”

According to this WikiLeaks-disclosed cable of 2007 the NSO “will be comparable to the NSA in the U.S.” Some 120 people are currently reportedly involved in the NSO. The Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of the Interior are responsibly for the NSO. The NSO is governed by the Ministry of Defense and directed by the head of the MIVD and the head of the AIVD. The NSO is absorbed by the Dutch Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU) that will have some 350 employees. The NSO has two stations for interception: 1) satellite traffic is intercepted in Burum; 2) high-frequency radio traffic is intercepted at a Dutch military base in Eibergen. The NSO itself has no legal ground for sharing the data they collect: the data must have been shared by either the AIVD or the military MIVD. Considering that the letter mentions “military operations abroad”, the MIVD is likely the sharing party.

In Snowden-documents, the Netherlands is listed as a Third Party member of the (14 Eyes group that form the) SIGINT Seniors Europe (SSEUR). Peter Koop notes:

“Being a 3rd Party means that there’s a formal bilateral agreement between NSA and a foreign (signals) intelligence agency. Probably the main thing that distinguishes this from other, less formal ways of cooperating, is that among 3rd party partners, there’s also exchange of raw data, and not just of finished intelligence reports or other kinds of support. Also both parties have a Special Liaison Officer (SLO) assigned at each others agency.

It’s not quite clear what the initial 3rd Party agreements are called, but we know that later on specific points are often laid down in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). An example is the Memorandum of Understanding between NSA and the Israeli signals intelligence unit, which was published by The Guardian on September 11, 2013.”

In the full Signal Profile diagram (.pdf) from BOUNDLESS INFORMANT about the Netherlands that was published today by NRC Handelsblad, the Sigint Activity Designator (SIGAD) “US-985Y” allegedly refers to the metadata that the MIVD provides to the NSA. Next to “US-985Y”, we see “1.831.506 Records” mentioned. The metadata concerns PSTN traffic, which can concern both mobile and landline communications. [UPDATE: the Minister stated that it did involve metadata about mobile calls, but about radio traffic and calls made via satellite phones.] Considering that the current Dutch law only permits undirected interception of non-cablebound communications (satellite and HF radio), landline traffic can only be legally intercepted if the end-to-end communication with the landline contains at least one wireless hop (e.g. Inmarsat).

The Dutch Parliament submitted a list of questions (.doc, in Dutch) that must be answered by the minister of the Interior (Ronald Plasterk / @RPlasterk) by February 10th, with the support of the minister of Defense (Jeanine Hennis / @JeanineHennis). On February 11th, the minister of the Interior will have to discuss these matters — and notably, explain the incorrect claims he made last October and November.

EOF