On December 16th 2015, the Dutch government submitted a “year plan letter” to the House of Representatives that covers the outlines of the General Intelligence & Security Service (AIVD) priorities in 2016. It is a follow-up to, and references, the first-ever year plan letter, submitted on June 23rd 2015. A translation of that earlier letter is available here.

The remainder of this post consists of a translation of the paragraphs that describe the focus areas regarding intelligence. Links, parts in [], typos and translation errors are mine.

[…]

National security and the role of the AIVD

Security is a core task of the government. The AIVD ensures national security by timely identification of threats, (political) developments and risks that are not immediately visible. To this end, the AIVD carries out domestic and foreign investigations, taking into account the safeguards of the Dutch Security & Intelligence Act of 2002 (.pdf) (Wiv2002). Collecting and interpreting intelligence is not an objective on and by itself. It is an essential condition to thwart terrorist attacks, disrupt terrorist traveling, detect espionage, and, more generally, support government policy to protect the democratic rule of law and other important state interests. The AIVD shares specific knowledge and information with its partners (for instance public administrators, policy makers, the National Police) and instigates other organizations to act.

Integrated Intelligence & Security Policy [Dutch: “Geïntegreerde Aanwijzing I&V”]

On June 23rd 2015 I informed the House of Representatives about the priorities and accents of the AIVD in 2015 (Parliamentary Papers 30 977, nr. 119), for the first time on the basis of an Integrated Intelligence & Security Policy. This Integrated Policy describes the intelligence needs of various intelligence consumers and is the basis for the year plans of the AIVD and the Military Intelligence & Security Service (MIVD). The Integrated Policy also takes into account prior budgets increases appointed by the government for the multi-year budget of the AIVD. The priorities and accents laid down in my letter of June 23rd are largely continued in 2016, because the Integrated Policy lays down the intelligence need for multiple years. At the same time it must be observed that worrying developments keep taking place within various existing areas of interest. The threat concerning jihadist terrorism, the instability at the borders of Europe, the large increase of migration flows and the changes in global power relations require undiminished attention and efforts within the AIVD’s investigations.

Priorities and accents of AIVD investigations

Concerning the legal tasks of the AIVD, insight is given below into the (changed) priorities and accents that are put central in 2016 in each focus areas:

Jihadist terrorism

The Netherlands has a terrorist threat level that is qualified as “substantial” since March 2013. In my letter of June 23rd I describe the current developments concerning jihadist terrorism, such as regarding the threat from jihadists from the Netherlands that have traveled abroad, jihadist groups that have an international agenda, and the increasing role of old transnational networks. I also state that different, unrelated elements can come together, such as mavericks, sympathizers, diffuse local networks, and relations or inspirations with other networks and groups. These threats remain current. The tragic events in Paris on November 13rd emphasize this. The efforts of the AIVD therewith remain focused, undiminished, on the timely identification of said national and international jihadist threats, to provide relevant government organizations with perspectives to act. Furthermore, the efforts are focused on preventing Dutch youngster from traveling to conflict zones and on the timely identification of the threat from (returned) jihadist fighters. In addition, the AIVD attempts to disrupt the supportive and recruiting activities regarding participation in violent international jihad. Especially concerning this topic, active cooperation takes place with domestic and foreign organizations, including the NCTV, the National Police, the Public Prosecution Service, municipalities, and Child Protective Services. International cooperation takes place with various foreign intelligence & security services, and within Europe, operational information is frequently exchanged within the Counter Terrorist Group (CTG). In the Spring of 2016, the AIVD chairs the CTG, and the AIVD has prioritized the further intensification of this cooperation.

Migration flows

The AIVD investigates possible security risks for the Netherlands and Dutch interests as result of the strongly increased migration flows to Europe. This investigation takes place from the perspectives mentioned above, including (jihadist) terrorism, radicalization, left-wing and right-wing extremism and tensions between groups inside the Netherlands. Investigation into specific countries also takes place. Where necessary, the progress of these investigation is discussed at the national and international level with the AIVD’s partners.

Radicalization

In the coming years, radicalization of various groups inside the Netherlands remains a cause for concern. The persisting international tensions provide a breeding group that, in combination with the national situation and personal circumstances, in the near future keeps resulting in a climate in which radicalization takes place. The recent AIVD/NCTV publication “Salafism in the Netherlands, diversity and dynamics” provides the most recent insight in the anti-democratic and intolerant character of parts of the salafist spectrum, combined with the risks for the democratic rule of law that is associated with their growth as observed by the AIVD.

The AIVD emphasized that the threat that stems from (the growth of) radical islam in the Netherlands is twofold: on the one hand, it can result in violence in the form of jihadist terrorism. On the other hand, it can by itself pose a threat to the democratic rule of law, because of the intolerant and anti-democratic thoughts that are spread. The AIVD investigates both types of threats. The investigation of persons and organizations that propagate jihadist thoughts helps in getting timely insight into jihadists, and thereby facilitates the AIVD’s investigation of jihadist terrorism. The investigation into non-jihadist radical islam helps, among others, the NCTV, the local governments, and other relevant organizations in taking measures against individuals who instigate others into anti-integrative and intolerant isolationism.

Left-wing and right-wing extremism

With regard to the investigation of left-wing and right-wing extremism, the developments and related priorities and accents described in my letter of June 23rd remain in place. The investigatory efforts regarding this area of interest will be continued in 2016. The interpretation of the factual threat that the AIVD attributes to left-wing and right-wing extremism is essential in providing the NCTV and local and national authorities with perspectives for acting.

Proliferation of WMDs

WMDs are potentially a great threat to international peace and security. The Netherlands has signed international treaties focused on preventing the proliferation of such weapons. The joint Unit Counter-Proliferation of the AIVD and MIVD investigates countries that are suspected of developing WMDs and means of transmission, or already posses those, in violation of these treaties. The priorities for the (joint) investigation by both services remain in place for 2016.

Investigation of countries

The AIVD’s investigation of countries is carried out to provide the government with background information and perspectives for acting and to use in discussion on topics that affect the Dutch national and international political interests. This investigation is increasingly closely related to the AIVD’s security tasks. Countries regarding which a joint intelligence need is laid down for the AIVD and MIVD in the Integrated Policy are investigated in close (operational) cooperation and consultation with the MIVD. The intelligence need laid down in the Integrated Policy for investigation of countries remains unchanged in 2016.

(Digital) espionage and cyber threats

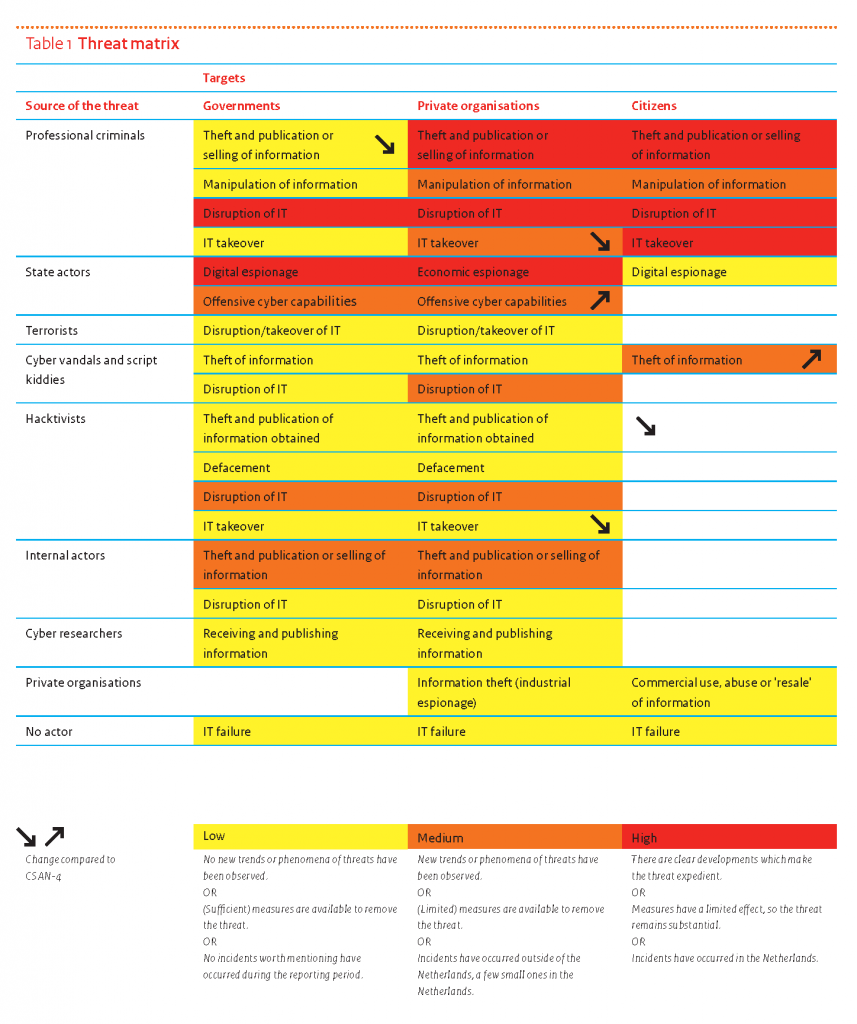

The intelligence need concerning foreign intelligence activities inside the Netherlands (espionage) or aimed against the Dutch interests remains unchanged in 2016. The investigation is aimed at identifying undesired activities and disrupting those, or by providing perspectives to act to the relevant authorities. Concerning digital espionage, anonymity and profitability of digital attacks provides unprecedented new possibilities for perpetrators and their clients to serve their political and/or economical interests. Examples of observed digital attacks, aimed at espionage and gathering sensitive and valuable information, are numerous and the threat and (potential) damage is great. It can also involve digital attacks aimed at sabotage or societal disruption. The AIVD investigates such cyber attacks and works closely together with the MIVD, the National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) and the NCTV.

[…further paragraphs omitted from translation concern the recruitment of new employees, the draft Dutch intelligence bill, security screenings, budget stuff, co-location of AIVD & MIVD at Frederikskazerne in The Hague, IT and accountability…]

(signed by Ronald Plasterk, the Minister of Internal Affairs & Kingdom Relations)

EOF