These priorities will guide activities and policy of the MoD in the coming years. The letter elaborates on these priorities, and addresses defensive, offensive, and intelligence aspects of cyber — and also mentions human and signal intelligence, for instance:

The remainder of this post consists of a translation of the Minister’s letter (some 4800 words).

Introduction

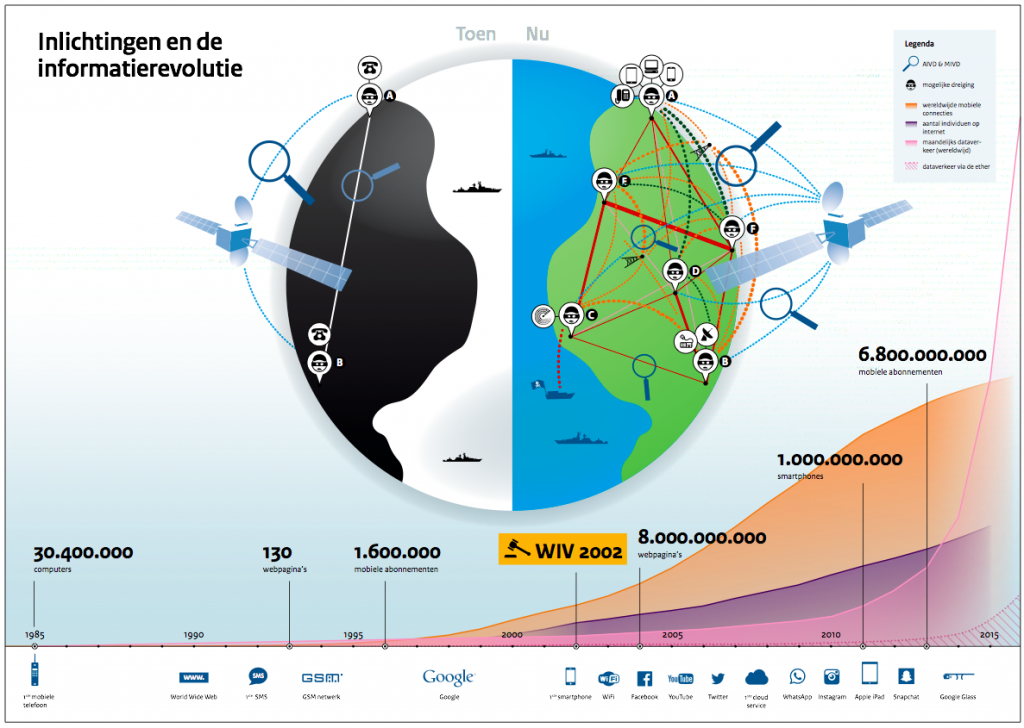

One of the most profound changes since the beginning of this century is the exponential development and the massive and global spread of digital technology. The Ministry of Defense is in many ways confronted with the consequences of this ‘digital revolution’. This ‘revolution’ offers opportunities for significantly improving the effectiveness and efficiency of military action, but at the same time introduces risks to uninterrupted functioning of the defense organization and national security that cannot be neglected. To stay ahead in the digital age, the MoD wants to join forces and deepen cooperation with its partners. The MoD will need to further develop to an effective and innovation-oriented organization, that manages to retain and stay of interest to cyber professionals. This revision of the Defense Cyber Strategy is aimed at that.

The Defense Cyber Strategy (Parliamentary Papers 33 321, nr. 2) of June 2012 has in recent years provided direction, coherence and focus to the integral approach of the development of military capabilities in the digital domain. This involves defense, offense and intelligence. Through this strategy, MoD recognized that digital means are increasingly an integral part of military acting. Since several years, the digital domain (cyberspace) is considered to be the fifth domain for military operations, besides land, air, sea and space. The MoD wants to use this domain optimally to increase her effectiveness. The Defense Cyber Strategy moreover emphasized that the wide dependency on digital means leads to vulnerabilities that need urgent attention.

In the last two years, the MoD made significant steps forward. The intensification that was started by policy letter `MoD after the financial crisis’ of April 28th 2011 (Parliamentary Papers 32 733, nr. 1) and its accelerated continuation in the memo `In the interest of the Netherlands’ (Parliamentary Papers, 33 763 nr. 1), are currently put into effect. The expansion of the Defense Computer Emergency Response Team (DefCERT), the strengthening of the intelligence position in the digital domain of the Military Intelligence & Security Service (MIVD), the establishment of the Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU) jointly with the AIVD (Parliamentary Papers 29 924, nr.113), and the launch of the Defense Cyber Command (DCC) in 2014, are the basis for the functioning and operating of the MoD in the digital domain. The intensification in the budget of 2015 of structurally 100 million euro (as of 2017) will, as is known, partially be used to strengthen the activity of the MoD in the digital domain. This is an annual investment that increases to 9 million euro as of 2017.

At the same time it is clear that the nature, speed and intensity of developments in the digital domain necessitate periodical revision and, if necessary, change of the strategy. Moreover, since the publication of the Defense Cyber Strategy in 2012, the security context has significantly changed as result of the destabilizing nature of Russia on the European continent, the conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa and the significant terrorism threat that comes with that. The cabinet policy letter `International Security Strategy’ (Parliamentary Papers 33 694 nr.6) emphasizes that the cabinet sees cyber threats as one of the most important future topics in this new security context.

In the General Meeting on digital warfare of March 26th 2014 I promised to revise the Defense Cyber Strategy. With the present letter I fulfill that promise. This revision is meant to give direction to the further development of and investment in digital means at the MoD in the coming years. The National Cyber Security Strategy 2 (NCSS 2) [.pdf] of October 2013 (“From aware to competent”) has served as a government-wide framework for this. The MoD, too, wants to improve its competence and effectiveness in the digital domain. On the basis of this revision, the MoD will in the coming months take the necessary next steps, including on the area of personnel, acquisition and innovation in the cyber domain. Deepening and connecting are keywords in that.

Priorities for the coming years

The principles underlying the Defense Cyber Strategy of 2012 remain relevant. Now that the foundations for defensive, offensive and intelligence means have been built, the present revision is about shifting accents, settings new objectives, and reformulating priorities.

Considering the necessary further strengthening of her digital means, the MoD in the coming years wants to focus on creating the right conditions for success in the digital era. Priorities are:

1. attracting, retaining and developing cyber professionals;

2. increasing the possibilities within the MoD to quickly innovate in the digital domain;

3. joining forces at the MoD and intensifying the cooperation with partners;

4. widening and deepening knowledge of the digital domain within the MoD (including the strengthening of cyber awareness of the entire organization).

By actively working on these priorities in the coming years, the MoD wants to maximally support the strengthening of her digital means. The priorities for the further strengthening of the digital means of the MoD are:

5. digital defensibility of the MoD;

6. intelligence capability of the MoD in the digital domain;

7. development and use of cyber capabilities as an integral part of military operations (defense, offense, and intelligence).

These seven priorities are explained below. They replace the priorities laid down in the Defense Cyber Strategy of 2012.

CREATING CONDITIONS FOR SUCCESS IN THE DIGITAL ERA

1. attracting, retaining and developing cyber professionals

Smart, competent and motivated cyber professionals are the most important ‘capabilities’ that the MoD must possess in the digital domain. To be successful in the digital domain, deep knowledge is indispensable, and this knowledge primarily is held by individuals. The MoD will have to put in much effort in the coming years to be of interest to and be able to retain sufficient people with specific knowledge. Because of shortage on the labor market, competitive recruitment and a flexible approach to employment requirements are necessary. Also, alignment is important of the MoD’s personnel policy for cyber professional with the public and private partners. The MoD will furthermore need to leverage the unique significance of her work and the meaning that employees derive from it.

To be attractive to cyber professionals, and to take into account the specific characteristics of this field, the MoD will be flexible with personnel policy. The `Agenda for the future of MoD personnel policy’ (Parliamentary Papers 34 000 X) and the measures that follow from the final report of the temporary committee on government IT projects [.pdf] serve as a basis as much as possible. Because specific knowledge and competences are important in the cyber domain, restrictions that follow from the placement policy of military personnel (such as limited placement period, function assignments, and the system of ranks) must be avoided as much as possible. The MoD will also have to be flexible in salaries to attract and retain cyber professionals.

The MoD also wants to position as an MoD-wide field, by promoting the development of career paths and the exchange of personnel between organizational parts of the MoD. The cooperation and exchange with public partners, such as theNational Cyber Security Center (NCSC), and with private partners are of importance. The cyber chair at the Netherlands Defense Academy (NLDA), the Cyber Education Designation by the Chief of Defense (CDS) and the development of cyber education by the Defense Cyber Expertise Center (DCEC) will contribute to an education and training policy tailored to cyber professionals. Cooperation with international partners, such as the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence (CCD COE) in Tallinn, will in that context have a significant place. The MoD also seeks cooperation with external partners such as universities, renowned educational institutes and the private sector. Lastly, the MoD will expand the number of cyber reserves in the coming years.

2. Effective innovation and acquisition

To be able to effectively innovate and acquire, the MoD will adjust regular process where necessary to the specific characteristics of this dynamical domain. The development and production of weapon systems usually take year. In the digital domain, however, developments are moving rapidly and there is an innovation cycle of months instead of years. Moreover, the development of digital technology is often difficult to predict. To quickly meet an operational need, it is necessary that the MoD can itself develop digital means using commercially acquired digital technology (‘rapid tool development’). The development of digital means for offensive use requires self-developing capability (supported by Concept Development & Experimentation). The MoD will also introduce faster en simpler acquisition and innovation procedures for the digital domain.

3. Joining forces and cooperating

The MoD’s cyber strategy entails an integrated, MoD-wide approach, in which the scarce cyber knowledge, means, personnel and capabilities will be joined as much as possible. Furthermore, close cooperation with national and international partners is of the essence to achieve the MoD’s objectives in the digital domain.

Within the MoD

For the protection of our defense networks, the use of cyber means in military operations, or the gathering of intelligence, often the same knowledge, skills, techniques and materials are used. Therefore it is important that various sections of the MoD work as integrated as possible. This leads to synergy, necessary knowledge sharing, and an effective and efficient use of scarce means and expertise.

The extent and way in which various organizational sections cooperate in the digital domain, is related to the MoD’s tasks on this terrain. This can vary from exchange of employees and the establishment of highly classified connections, to the use of common sensors and supporting information systems. The way in which knowledge and means are bundled also is influenced by legal frameworks and obligations. The Intelligence & Security Act of 2002 (Wiv2002) provides special powers to the MIVD, and a framework for (inter)national cooperation and confidential information exchange. The Royal Military Police (KMar) carries out its tasks on the basis of the Police Act of 2012 (Pw2012). Nonetheless, taking into account the legal framework, more intensive cooperation within the MoD on the area of knowledge and innovation, personnel policy, education and training is possible. The synergy between various parts of the MoD will therefore be actively promoted. In that context, the MoD will also promote co-location of cyber experts.

Together with other parts of government

Due to the interconnectedness in the digital domain, the effectiveness and security of the MoD on this terrain are closely related to the digital defensibility of partners. The classical distinction between military and civil, public and private, and national and international dimensions is less sharp in the digital domain. For instance, national security may be threatened by a large-scale digital attack on one or more public or private organizations. To enhance national digital defensibility, structural cooperation between public and private partners is of the essence. Agreements exist with the National Cyber Security Center (NCSC), that acts as national coordinator, about mutual support and military assistance in the cyber domain. The MoD and NCSC will keep cooperation closely in the interest of a joint view of digital threats and optimal coordination of operational activities. For instance, joint exercises are carried out to further improve the crisis management structure and deepen the civil-military cooperation.

Concerning the KMar, the MoD, as force manager, cooperates closely with the Ministry of Security & Justice and the Public Prosecution Service. The KMar carries out its task on the basis of the Police Act of 2012 and under the authority of, among others, the Public Prosecution Service and the Minister of Security & Justice. Digital technology is increasingly important here as well, for instance in the context of information-driven operations. For the MoD, the police tasks of the KMar within the armed forces are important for safeguarding a responsible military use of the digital domain. The KMar must for instance be able to review the legality of the use of cyber in national and international military operations, and investigate possible criminal offenses in the cyber domain against the armed forces. In addition, the KMar must be able to investigate possible criminal offenses in the digital domain by defense personnel and at defense locations. The digital domain will become more important in all legal tasks of the KMar. Therefore, the MoD will together with the Ministry of Security & Justice and the Public Prosecution Service examine what is needed to equip the KMar for this.

Private sector

The private sector is an important driver of knowledge development and innovation in the digital domain. The Netherlands Defense Industry Strategy (DIS) also shows this. Active cooperation with the private sector is of great importance. Joint research programs. developments of capabilities, and cooperation in education and training are central in this. These can provide important impulses for the development of the various digital means at the MoD.

International partners

Internationally, the MoD specifically seeks cooperation with like-minded countries. The Netherlands sees an important supporting role for the NATO, among others by establishing security standards for member countries, promoting interoperability, and better information and knowledge exchange. The cooperation between NATO and the private sector in the context of the NATO Industry Cyber Partnership (NICP) is relevant to the MoD. In the EU, cooperation within the European Defense Agency (EDA) is important, in which the focus is given to joint research into methods and techniques.

4. Knowledge and cyber awareness: widening and deepening

The pace of technological developments and the variability and unpredictability of the digital domain emphasize the necessity to keep investing in the knowledge level at the MoD. Cooperation and knowledge management are central. The Netherlands Defense Academy, the Defense Cyber Expertise Center (DCEC) and the Defense Staff will promote an innovative and experimental working climate at the MoD. The JSCU, too, will actively contribute to this. Lastly, education and training ensure that cyber knowledge is embedded in the entire defense organization. The DCC will initiate and facilitate education and training that is important at all levels of the organization. The themes will vary from cyber awareness to expert-level skills, depending on the target audience. The DCC intensively cooperation with the warfare centers of other parts of the armed forces, the knowledge elements within the MIVD, the Joint Communications & Information Services Command (JIVC) (including DefCERT), the Chief Information Officer (CIO) and the MoD’s Security Authority.

Structural approach of cyber awareness

It is necessary that defense personnel at all levels of the organization are aware of the possibilities and dangers of the digital domain. Employees can unintentionally pose a risk for the MoD’s digital security through improper or careless use of IT means. To counter this, the MoD will structurally address this in all educations and training. For instance, the Defense Security Authority had already developed course materials and a “digital driver’s license” for defense personnel. Education and training will also be increasingly focused on the possibilities that digital means provide for carrying out defense tasks. Cyber operations will be increasingly important in the design, planning and execution of exercises. The MoD will also train employees and military units to operate under circumstances in which they temporarily cannot use the (full) functionality of networks and systems. Lastly, the MoD will invest in the training of all IT and CIS employees, so that they can detect cyber attacks faster and take the right measures.

Cyber awareness is not only of great importance to the MoD. The same holds for national and international partners. Therefore, the MoD cooperates with (security) partners, such as in the annual Alert Online campaign (aimed at citizens, the government, and the private sector), that will be coordinated by the NCSC.

FURTHER STRENGTHENING OF DIGITAL MEANS

5. Strengthening digital defensibility

The armed forces are increasingly dependent on the reliability of information. They also strongly rely on high-end communications and information systems, networked weapon systems and logistical systems. Both in military operations and overall operations, the MoD strongly depends on these systems to ensure deployability of the armed forces. The amount of data generated by sensors, weapon systems and command systems (SEWACO systems) and networks is increasing exponentially. Defense networks and systems are furthermore vulnerable to manipulation during development, production, transport and maintenance. Not only the security of systems and networks, but also the security of information itself is thus of the essence. Exclusivity (only authorized access), integrity (no unauthorized changes) and availability (access) of information are paramount.

The Cyber Security Assessment Netherlands 4 (CSBN-4) shows that digital threats are increasing and are becoming more complex and advanced. The MoD and partners increasingly deal with increasingly aggressive forms of espionage, crime and other activities such as cyber sabotage. This not only involves known and common malware. A more urgent problem are targeted, advanced and covert digital breaches, often carried out by by state actors, that cannot be adequately countered through regular security measures. This threat is significant. Non-state actors are an increasingly large risk as well. The knowledge, means and techniques to carry out advanced digital attacks are becoming accessible to everyone.

The use of digital means in military operations has also increased, and is being developed. A cyber attack on IT, sensor, weapon and command systems, or operational logistics, is a severe threat to the deployability and effectiveness of the armed forces. This threat is not limited to mission areas, but also to defense networks and systems elsewhere in the world, and it can also be aimed at Dutch vital infrastructure or allies.

A fully `waterproof’ digital defense is infeasible. By quickly detecting anomalies in (vital) systems and taking extra measures, the damage can be mitigated as much as possible in the case of digital espionage or sabotage. Intelligence are indispensable to act against vulnerabilities in, and threats against networks and systems.

As described in Chapter 4, digital defensibility will be a prominent part of all defense training. The MoD will also establish one Security Operations Center (SOC), in which all management organizations cooperate to monitor and defend all networks, IT services and SEWACO systems of the Netherlands and in mission areas, day and night. This SOC will get extra personnel and will closely cooperate with DefCERT. In case of incidents, DefCERT coordinates contact with other CERTs, collects information about digital vulnerabilities, and provides advice about measures. An independent position of DefCERT toward the SOC is of great importance. The MoD will furthermore keep investing in a high-quality intelligence position in the digital domain. Cooperation between intelligence and the management organizations is of the essence to the MoD’s digital defensibility. To support this, the MoD will prioritize the establishment of facilities that enable the involved parts of the defense organization to exchange highly classified information. It goes without saying the the MoD will renew the security of her systems continuously through the development of innovative protection, detection and mitigation measures. The MoD also requires suppliers to take similar measures. To ensure the security of IT facilities and the supply chain in the future as well, the MoD will change the so-called ABDO regulation. This describes how external service suppliers must handle the MoD’s confidential information.

The security, continuity and innovative power of the IT facilities of the MoD, and the improvement thereof as described in the vision on IT (Parliamentary Papers 31 125 nr.45), are of course important to the further improvement of digital defensibility.

6. Strengthening the intelligence capability in the digital domain

The global digitization of society has far-reaching consequences for intelligence work. The unstable international security situation demands a flexible intelligence capability to gather information at an early stage, as needed for political and military decision-making. In the Netherlands, in allied contexts, and in (potential) mission areas, the MoD is confronted with technically advanced actors that pose a threat in the digital domain to the security interests of the Netherlands, and to a secure and effective execution of military operations.

The MoD needs insight into the means, intentions and activities of opponents to provide itself, the government and for instance allies perspectives of action. To strengthen the MoD’s defensive cyber capabilities, forward-looking capability for the protection of the MoD’s own systems is necessary. In addition, the MoD must be able to identify, counter and influence threats such as espionage. Offensive operation in the cyber domain also requires intelligence and preparatory intelligence activities, for instance to gain access to systems and map possible targets. These activities, preceding and during operations, are not limited to the digital domain, but also require other special means, such as human and signal intelligence. Locally obtained data can also be an important part of intelligence support preceding and during operations.

The MoD’s intelligence task is primarily carried out by the MIVD, under the responsibility of the Minister of Defense. The legal framework for the MIVD’s activities are laid down in the Wiv2002. On the basis of this law, the MIVD can carry out necessary actions to gather intelligence about the digital domain, and perform counterintelligence locally and abroad. It is, taking into account the legal requirements, permitted to enter computers. Considering the legal requirement to protect sources and methods, the law also provides the basis for confidential (inter)national cooperation.

To achieve and maintain sufficient flexibility in the digital domain, modernization of the Wiv2002 is necessary. The cabinet’s viewpoint concerning the renewal of the interception framework laid down in the Wiv2002 (Parliamentary Papers 2014-2015, 33 820, nr. 4) is of the essence to the MoD’s objectives in the digital domain. Access to cable telecommunications is a condition for identifying cyber threat at an early stage and to gather intelligence on the nature of the threat. The ability to explore the digital domain is moreover of the essence to intelligence operations and the support of cyber operations.

The MIVD will develop reporting mechanisms aimed at intelligence consumers. This can involve integrated analysis (so-called `all source products’), an exploration of cyberspace in relation to a potential mission area, or a signature of an advanced cyber threat. Cyber-related research questions will be included in the annual Defense Intelligence & Security Priorities (IVD) to further guide the MIVD’s efforts. The MoD also aims to further integrate the use of special means such as human and signal intelligence and an expansion of analysis capability in support of the information position in the digital domain. Advanced threats, such as aimed at defense-related industry and NATO institutes, are rarely limited to the Netherlands. International cooperation is therefore an important condition for countering such threats. Considering the classified character, this often takes place between intelligence and security services.

One of the core competences for the MoD and the Ministry of the Interior in the coming years is the JSCU, that the MIVD and AIVD established in 2014 (Parliamentary Papers 29 294, nr. 113). The MoD strives for the strengthening of this unit and the cooperation with the AIVD. In this joint unit of the MIVD and AIVD, technical knowledge and expertise concerning sigint and cyber are bundled. The JSCU acquires and disseminates data from technical sources, performs data analysis and technical investigations into cyber threats, and focuses on innovation and knowledge development.

7. Strengthening the use of cyber in military missions

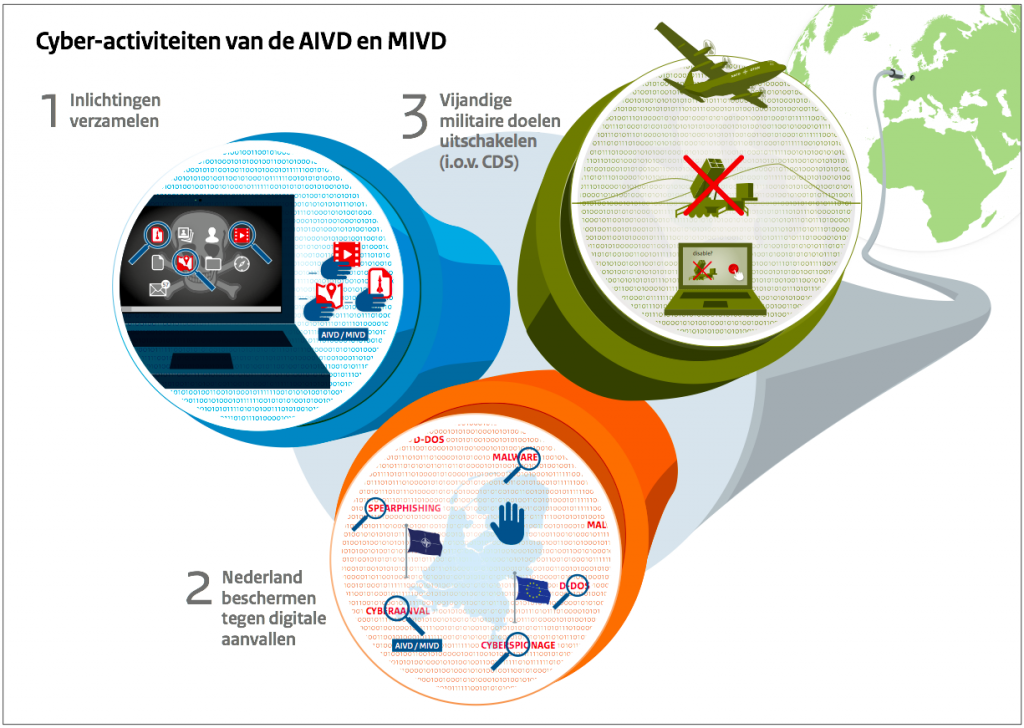

Operational digital means consist of all knowledge, means, and the conceptual framework to predict, influence or deny enemy action in a military operation, as well as the capability to protect own units against similar acts by the enemy. Operational digital means entail defensive, offensive and intelligence elements. They are inseparably part of modern military action.

Offense

By offensive cyber capabilities, the MoD means digital means that have as purpose to influence or deny enemy action. This takes place through infiltration of computers, networks, and weapon and sensory systems to influence information and systems. The MoD uses digital means only against military targets.

As a consequence of the intensive use of high-end communications, information and weapon systems, opponents too are depending on the reliability and availability of digital means. Offensive cyber capabilities can therefore, as a part of the total military power, provide an essential contribution to achieving the intended effects. They thereby are an important addition to existing means.

Defense

In a military operation, defensive measures against cyber threats are important to ensure the effectiveness and deployability of the armed forces. This starts in the integral preparation for a mission, among others by mapping the most important vulnerabilities in the networks and systems in a mission area, and mapping possible defensive scenarios. In a mission area, networks and systems must be continuously monitored, to intervene in case of breaches. In a cyber attack during a military operation, rapid response may be necessary. A definitive attribution (through intelligence about the way in which and by whom the attack was carried out, and with what objective) is essential. This emphasizes the need for evaluated and validated intelligence, that must be provided timely to the responsible commander. The responsible commander will have to weigh operational interests and intelligence interests, ensure the legitimacy of action, and often have to decide under time pressure. The mandate for the use of digital means will be determined per military operation, partially on the basis of the political risk, the potential collateral damage, the legal framework, and the necessity of secrecy.

Intelligence

A high-quality intelligence position at all levels is a condition for the execution of military missions. Especially in the digital domain, strategic and operational intelligence are interwoven, and must usually be acquired using high-end and sometimes costly means during a longer period. These can be appended by often locally acquired intelligence. An integral intelligence position brings the MoD in the position to properly estimate and influence opportunities, threats and risks.

In case of military operations abroad, the international legal framework is the primary basis and framework for the MIVD’s acting. The Wiv2002 will then be applied analogously insofar the circumstances in the mission area permit.

Tasks and powers

After a cabinet decision on the use of the armed forces, for defense if own or allied territory or the international rule of law, digital means of the armed forces are always under the command of the CDS. The decision to participate in a military operation may be accompanied by national limitations (caveats) on the use of Dutch units, specific weapon systems or interpretation of rules. This also applies to possible use of cyber units or cyber(weapon) systems. The use of cyber means for the third task of the MoD — the support of civil authorities in maintaining rule of law, fighting disasters and humanitarian aid, both nationally and internationally — takes place under civil authority.

If the Netherlands has a legal basis for acting, a clear assignment, purpose and Rules of Engagement must be formulated for cyber units . The legal framework is not different from that for the use of conventional means. The use of strategic cyber means will be determined primarily at the national level. The authority to use tactical cyber means will be determine per operation in the Rules of Engagement.

Capability development

To allow responsible and effective use of digital means in military operations, the MoD will address the following topics in particular:

– the further development of a Defense Cyber Doctrine;

– the development of offensive cyber means and of guidelines for the readiness of cyber units and cyber means that are flexibly composed;

– the setup of defensive digital means during missions;

– the development of cyber (intelligence) means for tactical use;

– the integral of cyber aspects in the operational decision-making process, preceding and during operations.

Offensive cyber means can vary from relatively simple and quick to develop means with a tactical impact to means with a high, strategic impact that require a long time to develop. The complexity and technological quality of these means mostly depend on the desired effects. These means are focused primarily on seizing information and communications networks, and sensory, weapon and command systems of (potential) enemies. Although relatively simple offensive cyber weapons can sometimes be effective for shorter periods, these capabilities distinguish themselves from conventional military capabilities by the fact that they can often only be used only once and are specifically developed for one purpose. It may involve complex means of which development, maintenance and use is labor-intensive and time-consuming. The preparation, development and use are a combination of specialized personnel, available technology, proper intelligence and processes, also to prevent undesired side effects of the use of offensive cyber means. The DCC ensures coordination between the various parts of the MoD and their digital means, and possesses specialists to carry out this task. This ensures an optimal use of cyber means in support of military operations, and prevents redundancy within the MoD.

IN CONCLUSION

The MoD has in recent years taken significant steps in the digital domain, and made significant investments. The Defense Cyber Strategy was the basis for that. The memo `In the interest of the Netherlands’ accelerated the implementation. The present revision determines the direction in which the MoD will further develop in the coming years, fully aware that the digital revolution requires flexibility in the application and financing of this strategy. To keep pace with the stormy development in the digital domain, the MoD will carry out a policy review in 2016 and 2017, which will be offered to the House of Representatives.

THE MINISTER OF DEFENSE,

J.A. Hennis-Plasschaert