UPDATE 2016-04-15: an additional NOS report states that the existing (targeted) interception power and (targeted) hacking power, too, will be subject to ex ante and binding oversight. The newly to be established oversight committee is entitled ‘Toetsingscommissie Inzet Bevoegdheden’ (TIB), and will consist of persons that have a background in the judicial branch.

UPDATE 2016-04-14: NOS reports that according to unnamed sources, the Dutch government will, with regard to the upcoming cable interception power, consider ex ante oversight by a new independent committee. (Note: ‘new independent committee’ presumably means it’s not about the CTIVD, the existing independent expert committee that has been carrying out ex post non-binding oversight since 2002.) Furthermore, requiring prior court approval for the interception of communications of lawyers and journalists will also be considered. The report states these topics will be discussed in the cabinet. The cabinet changed “purpose-oriented interception” (my translation from the Dutch word “doelgericht” used previously) to “investigation-bound interception” (my translation of “onderzoeksopdrachtgericht”). It’s just different words for the same thing: interception that is carried out in the context of an intelligence task, but that is not targeted/limited to specific known persons or organizations.

UPDATE 2015-07-02: the Dutch government released their draft intelligence bill into public consultation. Details here.

UPDATE 2015-06-01: changed “goal-oriented” to “purpose-oriented” everywhere, including in the (translated) diagram; it’s a better, less confusing translation (credits to A).

UPDATE 2015-02-11: the existing law contains the word “ongericht” (untargeted, unselected, bulk, mass). Yesterday it became clear that the bill, that Minister of the Interior expects to appear in April 2015, will no longer contain that word. Only the new word “doelgericht”, which I tentatively translated as “goal-oriented”, will be used. Goal-oriented does not exclude bulk interception, but aims to limit it to what’s necessary for specific investigations. An investigation can be long-running. The permitted (un)specificity of the definition of a “goal” depends on the phase of interception. If you permit me to speculate: I think it is very likely that an investigation can involve interception of all Tor traffic for the goal of identifying persons associated with terrorist use of the internet, such as public provocation (radicalisation, incitement, propaganda or glorification), recruitment, training (learning), planning and organizing terrorist activities).

UPDATE 2014-12-09: I translated the Dutch word “doelgericht” as “goal-oriented”. Someone suggested a better translation would be “targeted”. The reason I chose “goal-oriented” over “targeted” is that the latter, as perceived by my brain, suggests “targeted to a person or organization”, which is not how the notion of “doelgericht” is explained. For instance, it may very well be considered “doelgericht” to intercept as much Tor traffic as possible if doing so is necessary to achieve to the — hypothetical — goal/objective “deanonymize online extremism”. The notion of “doelgericht” could make indiscriminate surveillance a bit more discriminate, but there will be bulk interception nonetheless. In Dutch, “doel” means “goal” or “objective”; and “gericht” means “oriented”, “aimed” or, the word that I try to avoid, “targeted”. Assuming this notion will make it into law, which is still a long way ahead, we’ll have to wait and see how it will in practice be used to justify (AIVD/MIVD) and review (CTIVD) activities carried out in each of the three interception phases (collection, pre-processing, processing).

UPDATE 2014-11-28: an example use of bulk cable-intercept power would be to intercept all cable-transmitted phone calls to and from Syria, as part of current counter-terror efforts. The existing bulk ether-intercept power can only be used insofar phone calls are routed through the ether at some point and the intelligence services are able to intercept it there. The existing targeted (i.e., non-bulk) cable-intercept power can only be used on specific phone numbers are require that the identity of a person or organization is known prior to getting approval to intercept.

A first version of the below was posted on Cryptome.

In the Netherlands, interception powers of the intelligence & security services AIVD (historically focused on internal security) and MIVD (military) are regulated by the Dutch Intelligence & Security Act of 2002 (“Wiv2002”).

The AIVD and MIVD both have the power of (targeted) interception of communications in any form (cable, wireless, spoken, etc.) of specific persons or organizations. Exercise of this power requires advance approval of either the Minister of the Interior (in case of the AIVD) or the Minister of Defense (in case of the MIVD).

The AIVD and MIVD both also have the power of (untargeted) bulk interception of communications, but only for non-cablebound (i.e., wireless) communications. Under the current law, the AIVD and MIVD can carry out Sigint search against any wireless communications they want as long as that communication has at least a foreign source or foreign destination. (The latter restriction does not apply to Sigint selection; if authorization has been granted to select on the basis of identities, keywords or (other) characteristics, bulk interception for the purpose selection may also be performed on domestic communication; but there’s probably not a lot of it.)

In 2013, the a temporary committee named “Dessens Committee” reviewed that law, and concluded that in today’s world, the distinction between cable and non-cable communications can/should no longer be made. That committee then recommended, among others, to change the law and make it ‘technology-neutral’, i.e., to also allow bulk interception of cable communications.

In October 2014, the Dutch senate adopted a motion requesting the Dutch government to abstain from “unconditional, indiscriminate and large-scale” surveillance.

On November 21st 2014, the Dutch government published its response (.pdf, in Dutch) — accompanied by this diagram (.pdf, in Dutch) — to the recommendations of the Dessens Committee, and it turns out the Dutch govt indeed seeks to grant the power of bulk interception of cable communications to the AIVD and MIVD. Translation of said response and diagram are below. But first, here is a translation of a post (Nov 21, in Dutch) by the AIVD about the Dutch govt’s response (suffices as TL;DR):

Modernization of the Dutch Intelligence & Security Act of 2002, extra safeguards for privacy

The cabinet will modernize the Dutch Intelligence & Security Act of 2002. Minister Plasterk of the Interior and Minister Hennis-Plasschaert of Defense have explained the general ideas in a letter to Parliament.

The Intelligence & Security Act is nearly 15 years old and no longer suits current technology. 90 percent of telecommunications is transferred over cables. In the changed law, the AIVD and the MIVD are granted the power to also recognize terrorist threats, counter espionage, protect against digital attacks, support the Dutch security interests and military missions via the cable.

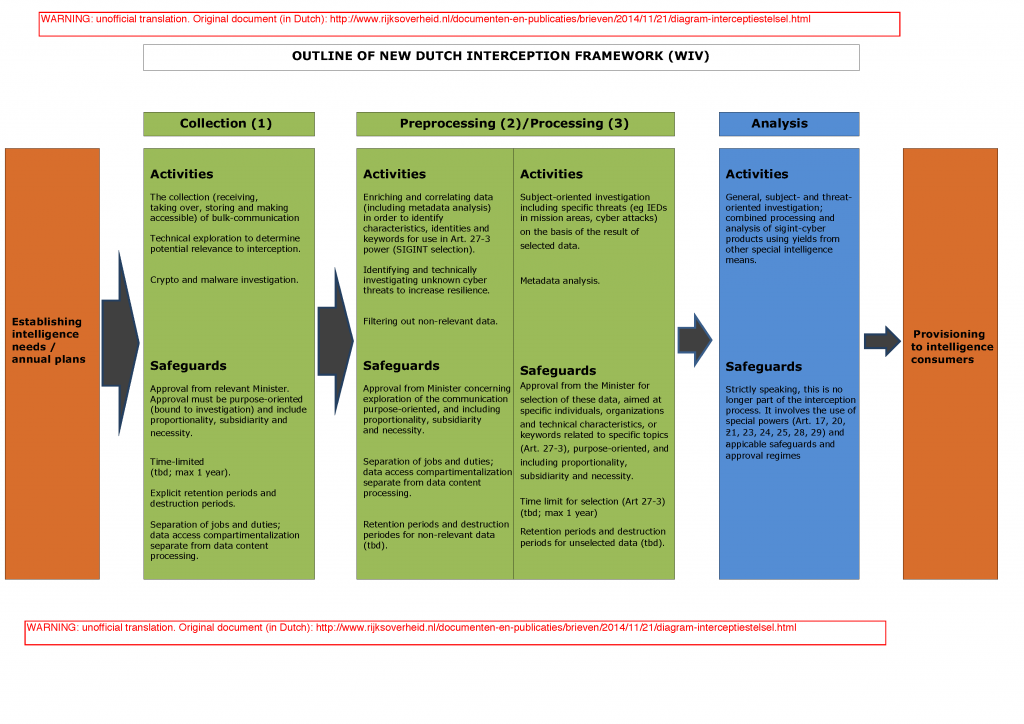

Interception of raw telecommunications data will be divided in three phases: collection, preprocessing and processing. Every phase requires separate approval from the Minister. In every phase, data may only be intercepted aimed at a specific purpose, after a review of proportionality, subsidiarity and necessity. In every phase, explicit retention and destruction periods apply. The intercepted raw data are only accessible by specific employees and for specific tasks. The approval from the Minister is subject of independent oversight by the Dutch Review Committee on Intelligence and Security Services (CTIVD). This framework ensures that the security services cannot search the collected raw data without restrictions.

The Wiv2002, that was established in the late 90s and applies since 2002, still makes distinction between ether and cable. The Dessens Committee reviewed the law and concluded at the end of last year that this distinction is outdated as result of ongoing technological developments. Nearly all telephony, internet, email, social media, apps and chat programs communicate over cables. Terrorist and combat groups also use this a lot, for instance for recruiting and command and control.

The cabinet therefore want to permit the intelligence and security services to intercept raw cable telecommunications under conditions. This concerns larger amounts of data, from which the services can select data of adversaries. An example is telephone communications to conflict areas. The safeguards in every phase of interception and processing of the data ensure that the government cannot spy on random email conversations of citizens, or eavesdrop on phone conversations. The privacy will thus be better protected.

The oversight will also be strengthened. If the CTIVD concludes, after review, that approval was given illegally, the Minister is required to reconsider that approval. When the Minister upholds his/her decision, it must be reported to the CTIVD and to the Parliamentary Committee for Intelligence & Security Services (CIVD), which can hold the Minister accountable.

These general ideas are developed in legislation.

The “legislation” refered to at the end is still being developed.

Here is an unofficial translation of the Dutch government’s diagram that outlines the new interception framework (click picture for larger image; also available as .pdf here):

Here is an unofficial translation of the full Dutch government response (note: non-italic parts in [] are mine; some phrases are ambiguous, that is sic, and I wasn’t confident to disambiguate):

1. Introduction

During the General Meeting of April 16th 2014, the government promised to establish the cabinet opinion about the advice by the Dessens Committee concerning special powers in the digital world. This opinion is presently provided. The Dessens Committee concludes that technology-dependent interception regulation that distinguishes between ether communications and cable communications can no longer be uphold, considering the fast technological developments concerning data traffic and communication. The committee found that change is necessary of regulations in the Intelligence & Security Act of 2002 (Articles 25 to 27). In the cabinet’s response to the Dessens report, submitted to Parliament on March 11th 2014, the cabinet stated it would study how this distinction can be replaced by a relevant norm that keeps safeguarding the privacy of Dutch citizens. Taking all things into account, the cabinet agrees with the Dessens Committee that this distinction is outdated and must be withdrawn, provided that a clear normative framework is provided that has adequate safeguards.

2. Developments in the digital domain and the necessity of a technology-neutral interception framework

In recent years, also as result of the great development of the internet, transmission of communication via cable infrastructure has increased explosively. In the Wiv2002, which was established in the late 90s and applies since 2002, this development was not taken into account. The current regulation of interception of telecommunication codified the then-current practice of the services, notably the former Military Intelligence Service (MID), in which interception of radio and satellite traffic was central. Different from the special power of targeted interception (Article 25 Wiv2002), which was formulated technology-neutral, the regulation of bulk interception was not formulated technology-neutral. The Dessens Committee thus concludes that the regulation of bulk interception in the Wiv2002 is outdated and does not reflect today’s necessary powers in the context of national security.

Besides an explosive growth of the amount of data that are produced globally (and that doubles every two to three years), it must be established that approximately 90% of all telecommunication is transmitted via cable networks. Nowadays, all electronic communication networks (ether and cable) comprise a communication network with global coverage.

For the (inter)national security interests of the Netherlands, and the deployment of the armed forces, a strong Dutch intelligence position is of vital importance, whether it concerns preventing terrorism, countering espionage, protecting against digital attacks, insight into threats for the international rule of law, understanding the intentions of some countries, insight into capabilities of risk countries, or proliferation of WMDs. Moreover, the services must be able to know about the threats that the society and the state are exposed to in the digital domain, in order to effectively arm against them, and allow others to take measures. This is of vital importance in the context of the National Cyber Security Strategy and in the light of the endeavors of the cabinet towards the digital government. The technical threats and possibilities manifest themselves both on cable and in the ether. The (potential) impact of cyber threats has become increasingly clear as result of various incidents. This not only concerns threats that can disrupt our cyber infrastructure, but also threats concerning integrity, availability and confidentiality of the information that all of us digitally record, use and exchange. To get insight into these threats, the services depend on adequate access to telecommunications.

The services must therefore have sufficient intelligence means and methods to collect, analyze, and report timely in the digital domain. Special powers that — under strict conditions — allow interception in the cable domain are indispensable. The use of these special powers by definition infringes upon citizens’ right to privacy. Considering the responsibility and task of the government to ensure security of its citizens, it is inevitable that the services collect and process personal data. This does not means that security and privacy are opposing interests. Through proper and purpose-oriented exercise of these powers, the government aims to support a secure society of fundamental rights, including the right to privacy. The goal-oriented character of the exercise of these powers based on legally defined tasks of the intelligence services ensures that “normal” telecommunications of citizens will not be infringed upon by the intelligence services. In other words: citizens need to fear that the government views arbitrary email conversations or eavesdrops on phone conversations. A right balance must continuously be found between the use of these powers and the ability to exercise fundamental rights. Necessary infringements on the right to privacy must be accompanied by adequate safeguards. In all cases, the CTIVD can review whether the requirements of proportionality, subsidiarity and necessity have been met.

3. Elaboration of cabinet opinion: new normative interception framework with adequate safeguards

3a Outline of new interception framework

The cabinet agrees with the Committee Dessens that a new balance must be found between security and privacy.

The cabinet concludes that a technology-neutral and thereby future-proof rephrasing of the powers of interception (as meant in Article 26 and 27 Wiv2002) is needed, albeit under simultaneous tightening of existing safeguards and introduction of new safeguards. The current law already exhaustively defines how the services are permitted to infringe upon the right to privacy through the use of their powers. The requirements of necessity, proportionality and subsidiarity must always be met. Moreover, the use of this power is only permitted if it is necessary in the interest of national security, as further defined in the tasks of the services.

Historically, the assumption was made that the closer the contents of telecommunications are involved, the greater the infringement on fundamental rights is. The distinction between content and non-content is, however, not the only defining element in determining the seriousness of the infringement and the approval regime that should be used. Also of importance are the scale on which data are collected and the methods used for (further) processing of the data.

Considering the above, the new framework for interception of telecommunication (“bulk”) is outlined in three phases. This outline will — as replacement of current Article 26 (exploration of communication) and Article 27 (bulk interception of non-cablebound telecommunications) — be further developed and explained in the bill that is to be prepared.

The phases are:

- purpose-oriented collection [in Dutch: “doelgerichte verzameling”] of telecommunications,

- preprocessing of intercepted telecommunications, and

- (further) processing of the telecommunications.

For clarification, these phases in the interception framework are depicted in a diagram that is appended to this letter. The diagram briefly denotes which activities each phase entails, and the safeguards that will be laid down in the new legal framework.

The following can be noted. Each phase has a well-defined purpose. In the first phase — collection — purpose-oriented relevant data are intercepted and made accessible (for instance by decryption), after advance approval from the Minister based on an investigative purpose defined as accurately as possible. Preparatory technical activities aimed at purpose-oriented collection of data and making the data accessible, can be part of this phase. Individuals or organizations are not yet being investigated in this phase, meaning that the infringement on privacy is limited. The second phase — preprocessing — is aimed at optimizing, in broad sense, the interception process, in the context of ongoing, approved investigatory assignments using the collected data. As this optimization can require metadata analysis or briefly taking a look at the contents of telecommunication , the infringement on privacy is greater than in the first phase. In the third phase — processing — selection of relevant telecommunications takes place, and selected data are used to gain insight into the intentions, capabilities and behavior of individuals and organizations that are subject of investigation. In this phase, subject-oriented investigation takes place, in which the contents of telecommunications and metadata are analyzed to identify individuals or organizations, and to recognize patterns.

An increasing insight into the personal life is thus obtained from phase to phase. The safeguards that will be laid down in legislation, must be stronger as the infringement on privacy is greater. Safeguards will be built in for all phases, which requires that both the use of the interception power (collection) and the processing of intercepts depend on (a) predetermined and time-limited approval from the Minister (a “warrant”, including a review of necessity, proportionality and subsidiarity), (b) purpose-oriented use [in Dutch: “doelgericht gebruik”] [Footnote: The term “purpose-oriented use” will be defined for the involved phase. In the collection phase, references can be made to investigation tasks as included in, for instance, the Foreign Intelligence Decision [in Dutch: “Aanwijzingsbesluit Buitenland”] or the Intelligence and Security Requirements Defense [in Dutch: “Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsbehoefte Defensie”]. The further down the process, the more specific the purpose will need to be formulated.] , (c) retention and destruction periods concerning the intercepted data, and (d) a (combined) framework of separation of jobs and duties, c.q. compartmentalization concerning the access to data in various phases and outside the interception process. These safeguards not only apply to interception of cable telecommunications, but also to the interception of non-cablebound telecommunications as meant in Article 27, first member, Wiv2002.

The latter currently does not require approval from the Minister. In addition to said safeguards, reporting will take place both for purposes of internal control and oversight by the CTIVD.

Through this framework of measures with purpose-oriented use of weighing of proportionality, subsidiary and necessity in the advance approval, the privacy of Dutch citizens is protected.

3b. Cooperation network providers

To exercise the power to intercept cable telecommunications as meant here, cooperation is in practice required from a network provider. This form of interception is always bound to a certain investigative purpose. The Ministerial approval to intercept (“warrant”) will be a mandatory legal assignment to a network provider to provide support for the interception. The most important condition that is to be laid down in legislation, is the obligated consultation between the services and network provider, prior to exercise of the interception power approved by the Minister. The services will not have unrestricted and independent access to Dutch telecommunication infrastructure. The mandatory cooperation will be supported by a requirement for providers to obtain relevant information if so asked.

3c. Metadata analysis

Use of intercepted telecommunications for the intelligence process can both concern use of metadata and use of contents. Currently, approval from the Minister is only required for the latter. The intercepted metadata can be subjected to a mere technical metadata analysis. and to more involved analysis, in attempt to identify subjects and recognize patterns. Both forms of metadata analysis are currently based on Article 12 etc. Wiv2002 and do not require approval from the Minister. In the new legal framework, the form of metadata analysis that aims to identify subjects and recognize patterns will be subjected to Ministerial approval. Here, too, requirements will apply of purpose-oriented use, necessity, subsidiarity and proportionality. In addition, a retention period and destruction period will be included.

3d. Enhanced approval regime

The approvals from the Minister that will be needed in the new framework, will be subjected to the system of reconsideration outlined during the General Meeting of April 16th 2014. That means that if the CTIVD, in the course of its legal oversight, concludes that an approval from the Minister was illegal, the Minister will be obliged to reconsider it. If the Minister upholds the approval, the CTIVD and the CIVD must be informed immediately. The CIVD can hold the Minister accountable if it desires to.

4. Data exchange with foreign services

The cabinet has earlier stated that the exchange of large amounts of raw data (“bulk data”) by the AIVD and MIVD with foreign services will be subjected to Ministerial approval. The Wiv2002 will be changed accordingly. Considering that international cooperation between intelligence and security services also involves exchange of other data, this legislation will not be limited to telecommunications data, but more generic.

The exchange of this sort of data will be safeguarded as follows:

a. Evidently, only data can be shared that was collected legally, with the criteria being met;

b. For every (intended) cooperation, a review will take place of criteria for cooperation with foreign services. These criteria involve the democratic setting of the service, the human rights policies in the country involved, and the professionalism and reliability of the services. The outcome of this review partially determines what form of cooperation, if any, is considered permissible, such as data exchange. If, according to these criteria, a cooperation with a foreign service involves risks, approval will be required from the Minister.

c. In the provisioning of data, it will always be required that the data will not be shared further.

d. Exchange of “bulk data” (large amounts of raw data) will require approval from the Minister.5. Concluding remark

The cabinet outlined the new interception framework and safeguards. In further development, the relevant providers of communication networks will be consulted. The outcome will be laid down in law and is currently being prepared. Evidently, this outcome will take into account not only the requirements from our own Constitution (Article 10 and 13), but also the relevant human rights treaties, notably the ECHR and European jurisprudence concerning interception of telecommunications and processing thereof. Combined with a stronger framework of oversight and complaints, as announced earlier, the cabinet is of the opinion that legislation as such will meet the constitutional requirements.

As a reminder: collection through interception and hacking, as well as some of the activities that the Dutch govt’s diagram lists under the preprocessing and processing phases, is carried out by the Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU) that is currently located at the AIVD’s building in Zoetermeer, and tasked as follows:

Article 1: Task description

The JSCU is a joint supporting unit of the AIVD and the MIVD that, commissioned by and under the responsibility of the AIVD and MIVD, is tasked with:a. the collection of data from technical sources;

b. making accessible data from technical sources such that the data are searchable and correlation within and between these sources is possible;

c. supporting the analysis, notably in the form of data analysis, investigation into cyber threats and language capacity;

d. delivering Sigint and Cyber capability in support of the intelligence requirements of the AIVD and the MIVD, potentially on-site;

e. innovation and knowledge development on the task areas of the JSCU.

Some things that come to mind based on all of the above (or rather: what’s missing):

- From CTIVD oversight reports 19, 26, 28, 31, 35 and 38 it is evident that for years, the AIVD and MIVD often fail to substantiate the use of their existing bulk interception power. For instance, the legally required motivation is lacking or insufficient, or necessity/proportionality/subsidiarity are not discussed — the CTIVD once observed reasoning that boiled down to “necessity implies proportionality” (which it does not). Said reports proof that it is a tenacious problem. Will the (oversight on) legality of the use of bulk interception powers improve with this new framework?

- Will the existing restriction that Sigint search is only permissible concerning communication that has either a foreign source or destination be upheld? Put differently, will that restricted be lifted, which would be a plausible move in the internet age, and (hypothetically) allow domestic-domestic bulk sigint search for whatever the Minister agrees to be “purpose-oriented” — a new term that is yet ill-defined and suggested will be defined relative to the phase / level of privacy infringement — and to meet necessity/proportionality/subsidiarity?

- Will the intended legal requirement for network providers to cooperate only involve passive taps, or also the possibility for the services to exercise their hacking power ex Article 24 via access to the provider’s network? (e.g. to carry out packet injection and, for instance, infect via fake or manipulated software updates, or infect or capture credentials via spoofed/MitM’d websites)

- Could it be “purpose-oriented”, proportional, necessary and subsidiary to collect all Tor traffic they can, for exchange with foreign services as part of “the multi-national effort” towards deanonymization of Tor traffic meant here? Note that (1) interception of bulks of encrypted communication may, by itself as something preceding preprocessing/processing/analysis, not be considered very privacy-invasive, and that (2) under current law, encrypted traffic can be stored indefinitely (Art.26 Wiv2002) until decryption (and decrypted traffic can be stored for up to 1yr). Furthermore, it is stated that the word “purpose-oriented” is to be defined relative to the phase — collection, preprocessing, processing — and that the intelligence services must specify the purpose “as accurately as possible”. Would a specification such as “deanonymize Tor traffic in support of national security or foreign intelligence” be accepted? If further limited as “for counter terrorism purposes”, would that in practice indeed ensure that deanonymization bycatch concerning other topics (crime, espionage, activism, etc.) will be ignored/destructed, and not exchanged with foreign services? [It should be noted, though, that perhaps other technical methods exist or will be developed aimed at deanonymizing Tor traffic that don’t rely on bulk intercepts, but that for instance rely on having control over certain and/or enough entry nodes, relays and exit nodes, or can be carried out without intercepting the full packet stream (e.g. only characteristics of the traffic; for example through netflows). Of course, for hidden services, successful deanonymization via browser exploits has been observed in the FBI’s “EgotisticalGiraffe” codename thing to deanonymize visitors of the Freedom Hosting .onion; successful use of traditional intelligence methods such as infiltration and stings seems to be observed in the arrest of drug dealers on Silk Road; successful use of leveraging OPSEC failures of an individual hosting a hidden service was observed in the arrest of the person behind Silk Road. Also, fake, manipulated versions of the Tor Browser have been observed here and here.]

- The govt states that the intelligence services will not have “independent” (in Dutch: “zelfstandig”) access to provider networks, i.e., they will not be granted the power to obtain access without consulting the provider networks (i.e., clandestine access to cables). But: don’t existing powers, which include access to private places and closed objects (Art. 22 Wiv2002), physical intrusion (Art.30 Wiv2002), the use and placement of technical eavesdropping equipment (part of Art. 25 Wiv2002), and hacking (Art.24 Wiv2002) already allow this? Also, the word “network providers” is, AFAIK, not well-defined in Dutch law, unlike, for instance, “provider of public electronic communication networks or services”. “Network provider” seems to include that category (i.e., the usual internet access providers and mobile telecom providers) but potentially also non-public networks such as the SURFnet NREN, and other closed user-group networks. Although there will be cases where traffic pertaining to such networks is exchanged via an upstream provider that is legally a “provider of public electronic telecommunication networks or services”. The latter of course applies to Google, Twitter, Skype etc., which are not “telecommunication services” under Dutch law.

- Could the new distinction between collection (considered by govt to be relatively little privacy-invasive) and preprocessing/processing (considered to be more privacy-invasive) in any way, to any extent, yield a situation similar to the U.S. government defining “collect” not to be “collect” until a human looks at what is collected?

- Will the Parliamentary CIVD committee, that is suggested should hold the Minister of the Interior and/or the Minister of Defense accountable for illegal approval, actually carry out that task adequately? Note that it is very likely that that process will take place in secrecy, because much of the information shared by the government with the CIVD is subject to NDAs.

- It is very premature, but: what will the Dutch senate’s opinion be on this proposal (note: an actual legislative proposal / bill does not yet exist, it is still being prepared at the time I’m writing this), considering that the Dutch senate in October 2014 adopted a motion requesting the government to abstain from “unconditional, indiscriminate and large-scale” surveillance? Put differently, will the proposal be sufficiently conditional, discriminate and small-scale, in the senate’s view?

Final note: it remains to be seen whether granting the bulk cable-intercept power will lead to a Dutch equivalent of GCHQ’s Tempora and/or to (unrestricted?) participation in the NSA’s Special Source Operations (SSO) that feed PRISM by hosting U.S. equipment for cable access (also see DANCINGOASIS / RAMPART-A (.pdf)). Factors of budget, capabilities, culture, law and the (quid pro quo) politics of intelligence exchange with foreign services will come into play. The Netherlands is a member (.pdf) of the SIGINT Seniors Europe (SSEUR) in relation with the U.S. government, but that does not mean that anything goes in NL->US data sharing. For instance, Dutch academics Beatrice de Graaf and Constant Hijzen in a book chapter on the Dutch intelligence community in a transatlantic context state (2012) that different privacy laws, human rights concerns and legal standards of the Dutch services “put a brake on their relationship with American services and agencies”. A historic anecdote from Dutchbat (Dutch battalion under U.N. command during UNPROFOR in Bosnia 1994-1995) that seems to illustrate this can be found on page 239-242 of Srebrenica: a ‘safe’ area — Appendix II — Intelligence and the war in Bosnia 1992-1995: The role of the intelligence and security services (.pdf, Cees Wiebes, 2003/2004):

A secret request to the MIS: a suitcase for Dutchbat

The MIS would have been able to acquire a good intelligence position if a secret American offer had been accepted. Staff of American, Canadian, British and Dutch intelligence services confirmed that the NSA intercepted only few conversations in Eastern Bosnia. The Americans had problems with their Comint coverage, although they intercepted fairly large quantities of information. Communications via walkie-talkies presented a problem however, as described in the previous section. This provided an opportunity for the Netherlands. The Head of the MIS/CO Commander P. Kok – he occupied this post from 1 January 1994 to 25 June 1995 – was approached by the CIA representative in The Hague immediately after Kok took up his post at the start of 1994. Dutchbat I was then about to leave for Srebrenica and the CIA made an offer ‘which you cannot refuse’.

Kok was told the following. The NSA, it appeared, had a serious problem: the service was unable to intercept communications via Motorola walkie-talkies in and around the eastern enclaves. The range of such communications equipment was no more than about 30 km. The Americans wanted to set up an interception network at various points in the Balkans, and envisaged Srebrenica as one of these points. They proposed setting up a reception and transmission installation at a number of OPs in the enclave. This involved equipment with the format of two ‘samsonite’ suitcases. One suitcase was for interception of the traffic, and the other provided a direct link to an Inmarsat satellite. The intercepted messages would be shared with the MIS. In exchange for this cooperation the MIS was also offered other ‘broad’ intelligence, taken to mean also Imagery Intelligence.

[…]

The CIA, also acting on behalf of the NSA, is said to have asked five or six times between March 1994 and January 1995 whether the MIS would cooperate in this project. Kok always had to reply in the negative. Kok was to try five times to get approval from the MIS/Army for this idea. He tried again with Bosch’s successor as Head of MIS/Army, Colonel H. Bokhoven. According to Bokhoven, Kok passed this request to him just once; he could not recall that Kok said that he had been approached by the CIA several times. Kok presented this to Bokhoven as a ‘spectacular’ proposal, but Bokhoven considered that the MIS should not cooperate in this project. He viewed it as an offensive intelligence task that did not fit the context of UNPROFOR, and also felt it was more suitable for the intelligence services of other countries. Bokhoven confirmed to the author that he had refused to cooperate in the installation of these Comint devices in the enclave.

[…]

Related posts:

- 2014-10-22: The Dutch Defense Cyber Command: A New Operational Capability

- 2014-10-16: New Dutch intelligence oversight report: the (il)legality of SIGINT carried out by the AIVD in 2012-2013

- 2014-10-03: Sigint: definition, qualities, problems and limitations (quotes from Aid & Wiebes, 2001)

- 2014-09-25: [UPDATED] Dutch Senate requests govt to abstain from legalizing cable SIGINT in a way that permits “unconditional, indiscriminate and large-scale” surveillance

- 2014-09-05: Overview of legal framework used to assess Dutch intelligence activities involving social media

- 2014-09-04: The (il)legality of hacking, acquisition, exchange of social media, webfora by Dutch intel agency in 2011-2014

- 2014-07-03: June 15th 2014: Dutch Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU) officially started

- 2014-06-30: Citing increased threats, Dutch govt partially reverses budget cuts on intelligence & security service AIVD

- 2014-05-06: Chairman of Dutch intel oversight to Dutch Senate: ‘I want to oversee ex ante (before the fact), not just ex post (afterwards)’

- 2014-03-03: [Dutch] Enkele gedachten bij ongerichte interceptie door IVD’s

- 2014-02-15: [Dutch] Meer context bij toezicht op selectie na ongerichte interceptie door AIVD uit CTIVD-rapporten 31 en 35

- 2014-02-14: [Dutch] Metadata: de cie-Dessens had het min of meer al begrepen!

- 2014-02-08: Broken oversight & the 1.8M PSTN records collected by the Dutch National Sigint Organization

- 2013-12-28: [Dutch] Afluisteren en SIGINT door AIVD/MIVD: toestemmingsverzoeken en normering

- 2013-12-04: Outcome of official review of Dutch Intelligence & Security Act of 2002

- 2013-12-02: Report of EU-US Working Group established re: NSA surveillance involving EU citizens

- 2013-11-09: Oversight on Dutch SIGINT is still broken

EOF

2 thoughts on “Some details on Dutch govt seeking bulk cable-interception for intelligence and security services AIVD and MIVD”